Lessons can be learned from report on West Virginia explosion

I am often frustrated with leaders who put commerce before safety. Mostly that is because I see the carnage from questionable leadership in the form of accidents related to a lack of training, poorly maintained equipment and apathetic procedure compliance. I believe we “own the dog” to be safe.

Jay Johnston |

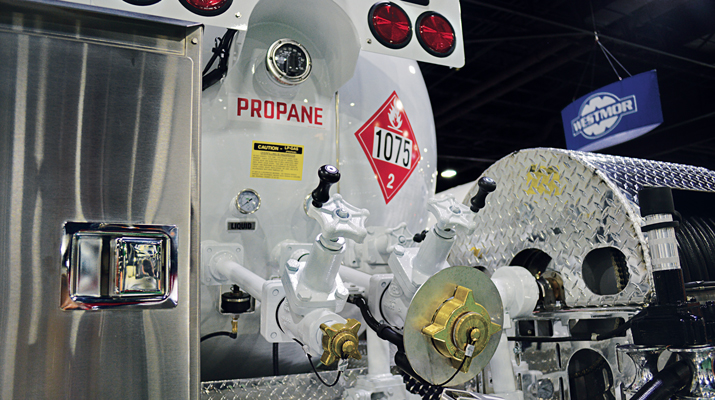

The U.S. Chemical Safety Board (CSB) released its accident-report conclusions and simulated reenactment of the tragic 2007 explosion in Ghent, W.Va., involving an attempted liquid transfer. The incident resulted in the deaths of two marketer employees, two emergency responders and serious injuries to five others. The report draws many conclusions from its investigation, and three things are clear.

The first is the importance of adequate procedure training. Often the advisability of such liquid transfer is questioned because of exposure to the public and proximity to other exposures. Transporting the tank to a remote location such as a bulk plant to perform the liquid withdrawal is a common option. However, that would require a permit, which involves certain precautions to comply with the special exemption issued by DOT.

This tank-to-stove connection was a quick fix by a service employee. |

In the real world, moving a competitor’s tank or working with a local authority of jurisdiction to get the competitor to move the tank makes the process of taking on a new customer more complicated than it needs to be. With experience and proper training, such liquid transfer in the field can be done safely.

In this case, it appears the valve was stuck in the open position. Once the cap was removed, fitting a transfer valve onto the liquid withdrawal valve or replacing the cap would be difficult.

The second observation is that the competitor’s tank, which was located against the building, had been previously filled and painted, implying knowledge of the tank not being in code compliance with NFPA 58. The only explanation for the competitor’s employees not previously noticing is lack of training to look for tank location code compliance. It is unclear whether supervisors were ever notified and failed to initiate action regarding the location of the tank.

The third thing that is clear is that the propane employees on-site and the emergency responders did not evacuate the premises promptly. Thirty minutes is a long time, and proper training of propane employees, EMTs and store employees would suggest initiation of evacuation immediately upon knowledge of the leaking tank.

At one of my recent safety seminars, one employee asked: What do I do if I notify my supervisor or owner of a safety problem and they fail to act? Am I personally liable if an accident occurs before they authorized the problem to be fixed?

Employees struggle with such questions daily. Barring gross negligence and assuming proper employee communication with employer about a problem, the employee is well insulated from personal-liability allegations.

The picture here shows a 20-pound cylinder hooked to a stove by a propane service employee as a temporary fix. The woman who owned the home called the manager to ask how long she would have the propane tank in the house. The manager pulled his best tech off his schedule and they promptly removed the tank, ran a proper line and made sure the system was secure. This incredible story is true.

What about other credible safety situations? How long is an appropriate amount of time to wait before addressing an issue of code or safety? How do you categorize credibility and sense of urgency? At your next safety meeting, I recommend you discuss such issues.

Safety success and accident elimination rely on owners and employees “owning the dog” when it comes to safety accountability. That includes having the courage to acknowledge when an apathetic or economic tail may be wagging the safety dog.

Jay Johnston (www.thesafetyleader.com) is an insurance agent, business insurance coach and consultant, safety writer and inspirational speaker. Jay can be reached at jay@thesafetyleader.com or 952-935-5350.