Finding good drivers is a tough haul

|

A nationwide shortage of truck drivers has propane retailers and distributors struggling to find enough operators to properly pilot their fleets, and may force employers to substantially up their pay scales if they hope to be in high gear when the snow flies.

The driver market is the tightest it has been in 20 years with a shortage of 20,000 truckers nationwide and a turnover rate of 120 percent, according to the American Trucking Associations, the largest national trade association for the trucking industry.

Good help is hard to find and keep, in part because of the outdoor labor required of propane drivers. |

ATA in May released U.S. Truck Driver Shortage Analysis and Forecasts, a report on the present and future of the long-haul truck driver pool. It predicts the shortage will surge to 45,000 in 2009 and 111,000 by 2014 if current demographic trends stay their course and if the overall labor force continues to grow at a slower pace.

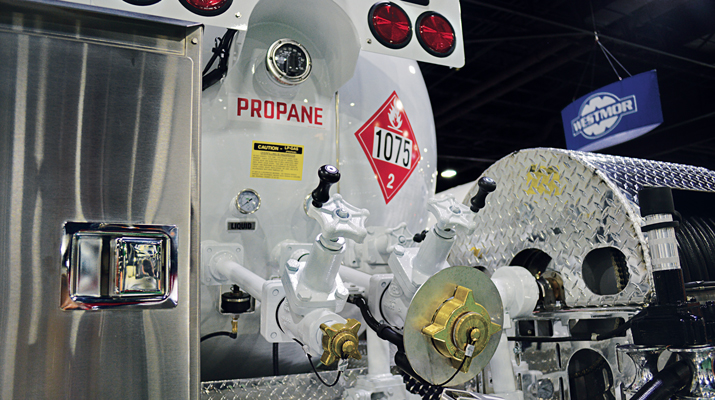

The driver pinch is exacerbated within the propane industry by the training, regulatory and security requirements for transporting hazardous materials.

Fingerprinting, background checks and other Transportation Security Administration (TSA) standards are among the factors pushing bobtail drivers away from the hazmat industry. Under typical pay rates, a person willing to drive a truck can make the same amount of money hauling freight without any of the hazmat hassles – and often without the outdoor labor involved in keeping propane accounts filled.

Growth of the Labor Force Will Slow |

The nation’s hazmat trucking sector is not offering a pay differential for the additional training and security certifications, so drivers often choose to haul straight cargo. Likewise, construction work tends to offer better pay than a driving job, frequently attracting those who might consider a bobtail operator’s position.

“It’s always a challenge because we compete with every other driving entity,” says Mary Reynolds, president and chief executive officer of the Western Propane Gas Association.

The propane industry does not track driver pay rates, which often are driven by what the local employment marketplace will bear. A propane retailer in a town undergoing booming development will have to offer wages matching or beating the construction industry pay. An especially tight applicant pool may require a recruitment bonus of some type.

Demographic Characteristics of Truck Drivers: 2000 |

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median hourly rate in 2003 for a “light delivery” driver was $11.65. In 2002, a “specialized freight trucking” driver averaged $14.69.

A recent newspaper advertisement for a regional truck driver in the Midwest offers a $16.80 hourly wage. In Texas, a hazmat-certified oil tanker operator nets a $500 sign-on bonus in addition to the undisclosed pay rate.

A bobtail driver applicant in Worcester, Mass. is promised $10.50 per hour. In Rhode Island the pay falls to $10.

Average Weekly Earnings of Truck Drivers: 1999 |

In fighting some of the highest driver turnover levels on record, various truckload carriers have said they would continue pushing up pay rates to curb what has become a continuous struggle to find and keep qualified drivers.

Some large publicly traded truckload carriers have said that they expected to continue increasing driver pay this year in efforts to boost driver retention. Analysts say several large truckload carriers increased driver pay between 8 percent and 10 percent in 2004. A major, over-the-road general trucking firm increased its wage packages 17 percent in 2004, with a similar raise set for this year.

OTR trucking firms are also addressing “quality of life issues,” promoting home-for-the-weekend opportunities, newer tractors and other amenities. Propane retailers have been implementing awards banquets, safety bonuses and other pat-on-the-back programs.

Driver shortages can be especially acute in specific areas based on localized conditions. A rural region, for example, may have few people to pick from as residents migrate to larger communities seeking employment.

A booming area is likely to have plenty of construction jobs offering higher pay than what a propane provider is willing to offer. Florida, for example, has a thriving construction trade in the wake of recent hurricane activity. And across the nation, housing construction is up, diverting drivers from all types of trucking jobs.

An aging workforce is another concern and younger applicants are not stepping up to replace them, says Reynolds.

“We’re very quickly coming to a bubble where many drivers will be retiring,” she says.

ATA projects that the number of men aged 35 to 54, which make up the primary driver demographic, will be flat or declining over the next 10 years.

Dramatic shortage

For the propane industry, meeting the hazmat qualifications makes attracting good candidates all the more difficult.

“It’s been a challenge of doing business for the past five years or so,” reports Steve Ahrens, executive director of the Missouri Propane Gas Association.

“The driver shortage is big, and it’s dramatic,” says Kelly Morrow, transportation director for CHS Inc., based in St. Paul, Minn. “On the hazmat side, it will get harder and harder to fill those positions.”

A lack of drivers means your trucks stays parked.

“Then you have two issues – one is with your customers, and the other is with making your payments.” Morrow says.

He expresses concern that people are not responding to ads pitching employment in the propane industry. Candidates who are interested often balk at the background checks.

“We have some who say, ‘Forget about it, I’ll just keep driving freight,'” says Morrow.

Michelle Swertzic, executive director of the Nebraska Propane Gas Association, agrees. “It’s a big issue. It continues to be more and more difficult to get people willing to go through the background checks and fingerprinting.”

Even the most willing candidates have been stymied, says Swertzic. For a time, the only TSA-sanctioned fingerprinting facility in her state was in Omaha; Nebraska is a huge state and traveling that distance was terribly inconvenient.

Nebraska Propane Gas Association officials eventually convinced the department of motor vehicles to open other fingerprinting centers in the state.

Other states face similar challenges. A two-to-three-month wait to get paperwork processed has been the norm in Iowa, according to a Hawkeye State propane retailer requesting anonymity.

In the propane industry, the shortage hits the smaller guys more than the larger guys, says Randy Knapp, executive director of the Wisconsin Propane Gas Association. Concerns over the issue were aired at the organization’s spring board meeting.

“With the smaller guys, if they lose a bulk driver (during the heating season) that can be catastrophic for them,” says Knapp.

Labor pains

The transportation director of a multi-state retail and distribution operation has had an equally tough time recruiting an adequate supply of drivers.

“To say it is difficult is an understatement,” says the executive. “A lot of the younger people are not interested in driving jobs that involve labor – and driving a propane truck involves labor. It’s not all about blowin’ smoke and jammin’ gears; these are all things that take the glamour out of it.

“You need reliable individuals who are going to approach the safety aspect. Those types of people are hard to find unless you come up with the money to hire someone away from someone else.”

That strategy carries a built-in disadvantage since the new driver is likely to leave your business in a lurch should greener pastures present themselves.

“A lot of individuals who apply don’t have hazmat training, so we have to broaden our training,” the executive says.

“When we finally get someone and they realize the training involved, they don’t want to be a propane truck driver. It’s a problem that’s going to continue to grow, especially in rural areas where your labor pool is severely limited. A lot of younger people move away to find a job with less labor involved.”

Mark Dixon, president of Transport Trends, a recruiting and training consultant to the trucking industry based in Canton, Mich., concurs.

“It’s only going to get worse. If you can go to McDonald’s and make $9 an hour, why would you pay to go to trucking school and (experience) all this grief and aggravation for the same amount of money?”

Grief and aggravation

Dixon says the security requirements are keeping new applicants away and experienced operators out of the business.

“Any specialized carrier (as with a bobtail or bulk transport) has more of a problem finding drivers. A lot of drivers are not even renewing their hazmat endorsements on their licenses. It’s like you’re signing up to join the Secret Service – they’d rather do drop-and-hook dry box driving (a traditional enclosed-cargo container tractor-trailer rig).”

As a whole, the trucking industry’s pay has failed to keep up with the times, according to Dixon.

“The wage rates haven’t followed cost of living increases. A car costs twice as much now than it used to, yet a trucker’s income remains static. Add in the TSA requirements, and the pay isn’t enough to compensate for all the grief and aggravation.”

Improving pay can help a company competing in a tight job market, Dixon suggests. Seeking women and minorities is another tactic, as is actively recruiting around fire stations, military bases and other institutions attracting people who are motivated, reliable and precise about following rules and regulations.

Bourne’s Heating Fuels & Service in Vermont has taken a seasonal driver and made him full-time to fulfill the company’s immediate needs, according to Peter Bourne, company president. They make an effort to stay in touch with all the workers during the off-season.

“We keep that contact going to make sure everybody’s happy,” Bourne says. “It’s either feast or famine. We have cycles. Right now we’re OK, but when the cold weather hits you don’t know if you’ll lose a driver. A lot of times I can’t find a soul interested in driving.”

Several of the drivers at a propane retailer in Texas have been employed there for close to 20 years.

“We pay them well – that’s how simple it is. We give them benefits and we treat them with dignity and respect,” the company’s co-owner says.

The pay packages and the pluses that come with driver longevity are factored in to the company’s operational plans.

“Of course it cuts into our margins, but that’s part of the business. We cross-train everybody – you can’t drive and spot problems [at the accounts] if you don’t know service,” she says.

Growing gallons

A propane retailer in Montana does nothing special to attract suitable candidates or keep them once they’ve hired on. Not surprisingly, his operation’s expansion plans are being stifled by a lack of drivers.

“We’ve grown and we need more coverage,” says the retailer. “The problem in our area is that there is a lot of construction going on, and with construction they make a lot more money.”

A new pay plan is in place at United Farmers Cooperative, headquartered in Shelby, Neb.

“They get an hourly wage plus commission,” reports Phil Pelc, the safety and compliance director.

He says the drivers realize that if they can keep their gallons steady or grow them that will be good for them.

It seems to be working. Of 12 drivers, 10 of them have been at UFC for more than 15 years. “We must be paying them pretty well to have them stay with us for this long,” Pelc observes.

He says the employment pool is tight and it’s tough to find someone just to stand outside and unload a truck at the full-service operation.

To combat these driver issues at AmeriGas, technology is on the job. The company is using a program called Driver Management Online, an Internet-based system that standardizes all driver hiring, driver qualification file maintenance, driver and employee training, accident recordkeeping and drug and alcohol programs.

“With 4,000 drivers it’s tough to handle that issue,” says John Rice, director of safety at AmeriGas.

“The system allows us to manage very well the hiring of our drivers. With the people that we’re hiring, we’re more certain that they’re quality drivers – and that will lower our turnover.”