2023 State of the Economy: Tricky terrain

Fasten your seat belts and enjoy the ride.

Higher consumer confidence predicted for 2024 can only help propane retailers. (Photo courtesy of Co-Alliance Cooperative Inc.)

Like airline travelers bracing for expected turbulence, business owners are preparing for a tricky operating environment in 2024. On the upside, the economy will continue to grow in the coming months, although at a slower pace. Consumers and businesses are both feeling fairly optimistic; unemployment remains low; capital investments are plugging along at a healthy pace; and the all-important housing market is burgeoning.

Throwing cold water on the good times, though, is a significant downer that no one can control: Higher interest rates established by the Federal Reserve to control inflation are putting a damper on business activity. Economists are taking note by lowering expectations for the next 12 months.

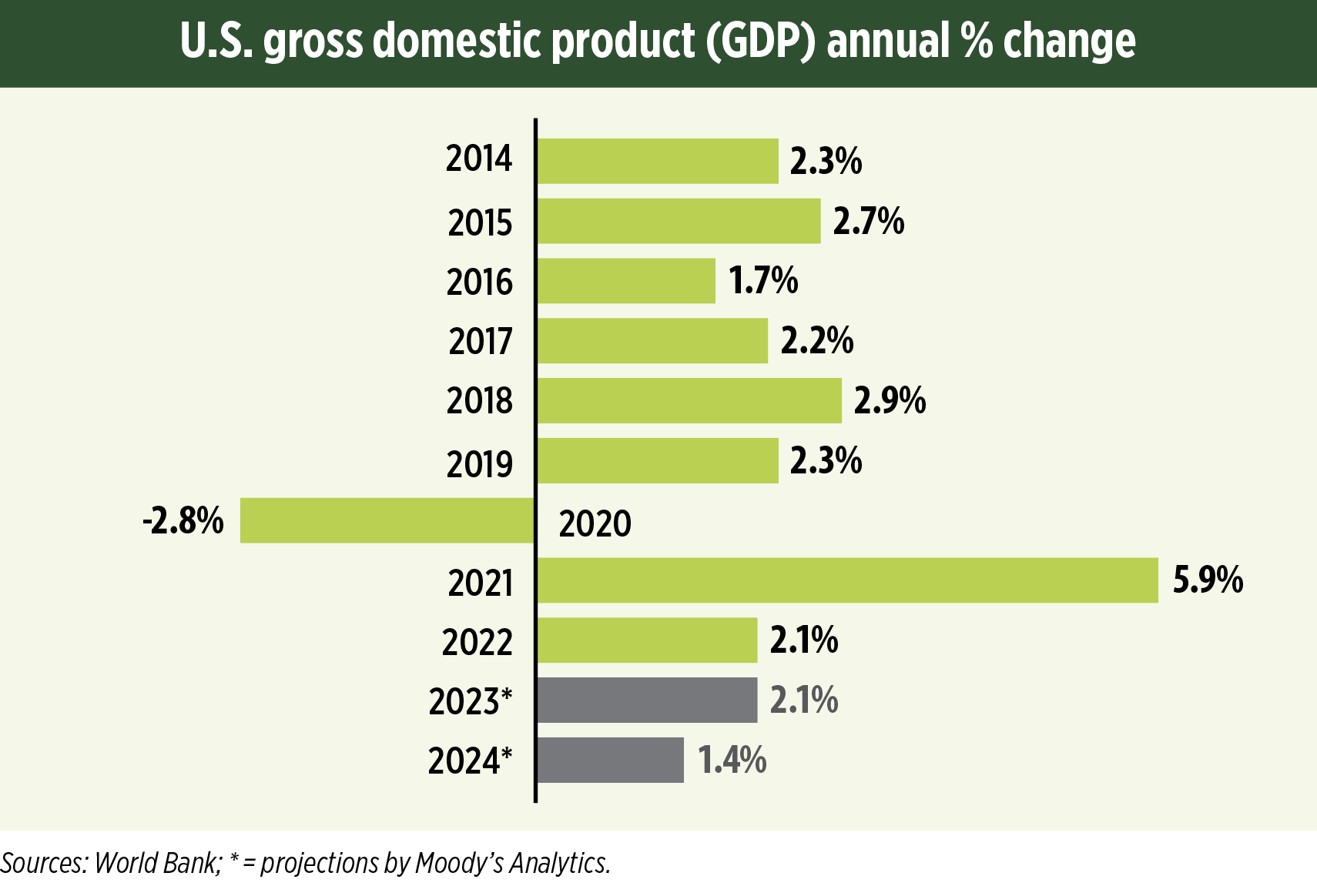

“We expect real GDP (adjusted for inflation) to grow 1.4 percent in 2024,” says Bernard Yaros Jr., assistant director and economist at Moody’s Analytics.

That’s slower than the 2.1 percent increase expected when 2023 numbers are finally tallied and below the 2-3 percent considered emblematic of normal business growth.

Slowing commercial activity will affect the bottom line. Moody’s Analytics expects a decline of 4.5 percent in corporate profits for 2023 and forecasts only a modest recovery of 0.3 percent in 2024.

Battling inflation

Reports from the field confirm the economists’ readings.

Owing to higher interest rates, economists predict slowing growth for 2024.

“Our members are experiencing a business slowdown, due largely to the effect of increasing interest rates,” says Tom Palisin, executive director of The Manufacturers’ Association, a Pennsylvania-based regional employers’ group with more than 370 member companies.

While businesses understand the need for higher interest rates, they nevertheless hope for early relief.

“If inflation does not continue to drop, interest rates will have to be increased further, which will be a big problem,” Palisin says.

So, are the Federal Reserve’s efforts paying off? There’s some good news here, as well as a sunny forecast. Moody’s Analytics expects year-over-year consumer price inflation to average 3.2 percent when 2023 numbers are finally tallied, down from over 6 percent a year earlier. Moreover, the number should continue to drop until it reaches the Fed’s target rate of 2 percent late in 2024.

Indeed, Moody’s Analytics believes the Fed will start to lower interest rates around June of 2024, although more slowly than previously anticipated because of persistent inflation and ongoing labor market tightness. Cuts of about 25 basis points per quarter are expected over the next few years until the federal funds rate reaches 2.75 percent by the fourth quarter of 2026 and 2.5 percent in 2027.

Feeling good

The public mood is a strong driver of the economy. And here the news is good.

“Consumer confidence has been trending higher, and I think prospects are good for it to improve next year,” says Scott Hoyt, senior director of consumer economics for Moody’s Analytics. “Things should normalize as the economy continues to grow and gas prices stabilize.”

One major driver of consumer confidence is a healthy job market.

“The unemployment rate has been very low, bouncing around between 3.5 percent and 3.8 percent for some time,” says Hoyt.

A slowdown in job growth orchestrated by the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes should moderate things.

“We think unemployment will trend upward a bit, ending 2023 around 3.9 percent and 2024 around 4.2 percent.”

Many economists peg an unemployment rate of 3.5 percent to 4.5 percent as the “sweet spot” that balances the risks of wage escalation and economic recession.

Low unemployment may fuel happy sentiments among citizens, but it presents employers with two practical challenges. The first is the need to raise wages to attract sufficient workers.

“Wage and salary income growth has been strong, fueled by a tight labor market,” says Hoyt. “We’re expecting it to increase just a shade over 5 percent, both for 2023 and 2024.” In 2022, the growth was a little over 8 percent.

Reinforcing the estimates of the economists, Palisin says his members have had to hike their compensation to remain competitive among themselves and other economic sectors. The group’s entry level hourly wages increased 8 percent to 10 percent in both 2022 and 2023, far higher than the historic average of 2.5 percent to 3.0 percent.

Problem No. 2 is a scarcity of workers. The inability to hire enough people – particularly of the skilled variety – can affect the bottom line. Two problems contributing to a labor shortage are the retirement of baby boomers and a post-pandemic reordering many people are making of their life goals.

“Demographic structural changes in the U.S. mean we just don’t have, in many cases, the number of workers needed in manufacturing to meet demand,” Palisin says. “That’s not going to change.”

The situation has become a bit nuanced as the recent economic deceleration resulted in a hiring slowdown.

“The labor market is still tight, but it’s not as bad as it was a couple of years ago,” says Bill Conerly, principal of his own consulting firm in Oregon. “While we still have more job openings than unemployed people, the margin is not as large, and we don’t have all the quiet quitting that we had before.”

While employers never like having to raise wages, putting a cap on paychecks has taken a back seat to a more urgent concern: keeping valuable talent from jumping ship.

“The big question now is not so much who can pay the most for entry level and skilled jobs, but what can they do to retain these folks within their companies,” Palisin says. “Manufacturing in the U.S. over the last year has continued to hire pretty significantly, and we’re not seeing a lot of layoffs, so that tells you that companies are hoarding talent.”

Employers are fine tooling their operations in the areas of workplace flexibility, benefits and culture changes.

Housing markets

Given the generally upbeat consumer sentiment, prospects are good for the housing sector, an important driver of the overall economy.

A lack of existing homes to meet consumer demand is fueling a rise in new construction. (Photo: BanksPhotos/iStock / Getty Images Plus/Getty Images)

“New home sales are running at the top end of the range set in the decade preceding the pandemic,” Yaros says. “One reason is that a lack of existing inventory is pushing buyers to consider new homes. The construction industry is stepping in to close the gap, and housing starts have exceeded expectations.”

The construction of new homes is being fueled by a cold, hard fact: There aren’t enough existing homes to meet demand.

“The 3.1 months’ supply of existing homes remains well below the four to six months of inventory that is considered a balanced housing market,” Yaros notes.

Strong demand caused a 10.3 percent increase in the median price for existing homes in 2022 and a 0.6 percent increase in 2023. A correction of 1.1 percent is expected in 2024.

For an explanation of the scarcity, look no further than the run-up in mortgage rates. The ultra-low interest rates of existing mortgages amount to a strong financial incentive for existing homeowners to stay put.

“Current homeowners had refinanced their investments at 3 percent or 4 percent,” Conerly notes. “Replacing what they had with better homes would require walking away from those mortgages to take on new ones at 7 percent. I think we’ll see this trend continue for another year, but I think we’ll also see a lot of strength in remodeling, and that will be financed probably with home equity lending or second mortgages.”

Business confidence

High interest rates, an inflationary environment and rising worker wages: a trilogy of challenges that in normal times would dampen business confidence. And there are other threats to corporate well-being, such as high energy costs resulting from the Russia-Ukraine war and an appreciation in the U.S. dollar that hampers export activity.

Despite all this, companies don’t seem to be planning any dramatic adjustments to their operations, in marked contrast to their cautious attitude of a year earlier.

“While our members have moderated their expectations for the future, they are still feeling slightly positive,” Palisin says. “One reason is that we seem to have avoided the recession that many were predicting.”

Moody’s Analytics believes that the nation will avoid a recession in 2024, attributing its forecast of a soft landing to resilience in labor markets and consumer confidence.

Another driver of optimism is a recent brightening of the supply chain picture.

“There has definitely been a shift in the awareness of the risks of doing business in China,” Palisin says. “This has resulted in a reorganizing of supply chains into nations such as Vietnam, Philippines, India, Mexico and the U.S. The jury is still out as to what nations will benefit most.”

Indeed, many businesses are taking action on their good feelings.

“The commercial sector looks very strong to me,” Conerly says. “Given the current level of interest rates, I’ve been surprised to see the healthy level of capital spending.”

Conerly said that manufacturing facilities seem to be the biggest gainers in non-residential construction, with new semiconductor facilities especially benefiting from the CHIPS Act. Suburban office construction has been doing surprisingly well, despite vacancy rates in urban centers. So have suburban neighborhood strip centers, which had been neglected for too long because of fears that Amazon would capture all of the retail business.

Conerly identifies three forces propping up equipment purchases. The first is the CHIPS Act and the construction of semiconductor facilities. The second is the automation being installed by companies nervous about being able to hire people. And the third is the trend toward reshoring by companies that are trying to shorten their supply chains.

Businesses looking to borrow funds to fuel capital investments, though, had best prepare for a tougher negotiating environment.

“The banking sector is in retrenchment, and lenders are becoming more risk averse,” says Anirban Basu, chairman and CEO of Sage Policy Group. “As a result, developers are having more difficulty lining up financing.”

Fueling the concern among financial institutions is a recent spate of loan delinquencies and bankruptcies. Banks are looking at their portfolios and seeing where they can tighten up. Companies holding inexpensive pre-pandemic loans will see an earnings hit when they need to refinance at 6 or 7 percent.

Keeping watch

In the opening months of 2024, economists are advising businesses to keep an eye on some key statistics to get an idea of how the year will turn out. Among them:

- Inflation.

“If progress in core disinflation stalls out, that would likely mean the Fed will keep interest rates at their current level for longer than we are currently assuming,” Yaros says.

- Employment.

“Total employment in the country is a good measure of current conditions,” Conerly says. “And any increase in initial claims for unemployment insurance could foreshadow a slowdown.”

- The yield curve.

“A reversion in which short-term interest rates exceed long-term ones could foreshadow a coming economic slowdown,” Conerly says.

Whatever the condition of the tea leaves, businesses in general will encounter a tougher operating environment in 2024, characterized by a need to finesse a tight labor market and reluctant lenders.

“In the coming year, we will face uncertainty about inflation and interest rates, shortages of labor, higher energy costs, a slowdown in China’s economy and recurring threats of a federal government shutdown,” Palisin says. “There are a lot of spinning plates in the air, and some of them may fall and crack.”