Beating the odds: Maintaining family-run businesses from generation to generation

Successfully transitioning to the second, third generations of family propane businesses is a challenging proposition.

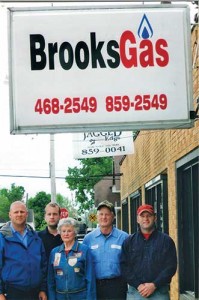

Brooks Gas has survived three generations of owners in the last 60 years in part through a simple process that exemplifies the meaning of family – sharing a meal.

John Brooks, third-generation owner, says the Missouri business has stayed in the family because he and relatives make decisions in a relaxed setting over lunch and dinner.

“We’ve never had formal meetings when making decisions,” Brooks says. “It’s all decided together, as long as one person takes the reins and the rest follow.”

While Brooks says he and his brother Joe co-own the company, they still get input from their mother, Mary Ruth, who has been working in the company’s office for more than 50 years.

“[Mary Ruth] has been a strong influence on keeping this company in business,” John says of his mother.

John says his son, Will, and Joe’s son, Brian, started working for the company recently. Both sons have said they want to stay in the business, giving John hope that Brooks Gas will enter fourth-generation ownership someday.

Although Brooks Gas gets some requests from MLPs to buy the company, John says the company doesn’t plan to sell anytime soon.

“If my brother and I reach our limit and our kids end up leaving the industry, we might consider selling,” he says. “But we seem to be locked in a deal where it’s a family business and it’s not going anywhere.”

Unfortunately, a third-generation family business like the Brookses’ is a rarity in the propane industry. According to John A. Davis’ book, “Enduring Advantage: Collected Essays on Family Enterprise,” only 30 percent of all family-owned companies pass to the second generation successfully and only 14 percent make it to the third generation. The numbers decrease exponentially further down the family line a business is passed.

Propane Resources, a business consulting company for the propane industry, has several insights to this statistic. Mark Bailey, Propane Resources CFO, says these statistics apply to most industries. He says a variety of factors influence why a business becomes more difficult to keep in the family as it’s passed down the generational line.

According to Bailey, passing ownership to dozens of grandkids can become a grind. Some kids or grandkids might not have the right qualities, personality, desire or finances needed to take on the business, he adds. In other cases, kids or grandkids have conflicting agendas about how to manage the business.

While the odds are stacked against a family maintaining a business across generations, family businesses aren’t necessarily doomed to fail. Bailey says there are situations in which family businesses can beat the odds, even if that means selling the business or making tough decisions.

Getting outside insight

The Brooks Gas family includes, from left, Joe Brooks, Brian Brooks, Mary Ruth Brooks, John Brooks and Will Brooks. Photo courtesy of Brooks Gas.

Founders of a family business hope they are creating a lasting entity that can be handed down two, three or four generations, but in most cases, this is an insurmountable task. Seldom does a succession-planning solution come overnight.

Gary Papay, president of CK Business Consultants Inc., says retailers can hit roadblocks when developing succession plans, especially because of varied agendas in a family. Papay recommends family businesses sit down with advisers and attorneys to get outside perspective and understand the value of the business before making any decisions.

Tri-Gas & Oil Co., based in Federalsburg, Md., got outside input on its business when it hired a non-family member as its CEO for a six-year period.

Keith McMahan, chairman of Tri-Gas, says the CEO had a “proven track record” and acted as a great liaison in supporting the second- and third-generation owners.

“It was a very healthy experience for our company,” McMahan says.

McMahan says he took on the chairman’s role of the National Propane Gas Association around the same time his three kids – Nash, Julie and David – were returning to the family business from college. He says the non-family member CEO helped prepare his kids when they were transitioning to leadership roles.

Nash now serves as the company president, Julie as marketing and community relations manager and David as retail operations manager.

“The timing of how things worked out seemed perfect,” Nash says. “Somehow all three of us kids found our way back to the family business with different perspectives and strengths, which is almost unheard of.”

Another way to get outside input in the family business is to let future-generation owners and managers get outside experience before returning to the company. One North Carolina propane retailer, which wished to remain anonymous, says its second-generation owner did that. The owner says outside experience helped him when he returned to the family business in the mid-1990s.

“I went to a management training program at a bank right after I graduated college,” the owner says. “It gave me a new perspective, seeing how another business and industry worked. It helped me to not be afraid to ask questions on how our business was run when I returned to the family company.”

When the second-generation company owner returned to the family business, he spent his first few years in the field delivering fuel, painting trucks and running gas lines.

“I had to get an understanding of what these guys go through every day in the field before I transitioned to a managerial role,” he says.

The second-generation owner had several ideas from his banking experience on how to improve the family propane company by integrating a new software program and a budget plan for customers. He shared the ideas with the company’s owners – his mom and dad.

“I did my homework before addressing Mom and Dad,” he says. “Before you present an idea to family members who have run the business for decades, you need to do your homework. You might be able to get that through an outside consultant.”

As the North Carolina company implemented the second-generation owner’s ideas, he says it nearly tripled its value because he sought outside resources to solve a company problem.

Personality and readiness

From left, Keith McMahan, Nash McMahan, Julie McMahan and David McMahan of Tri-Gas & Oil Co. Photo courtesy of Tri-Gas & Oil Co.

Not every owner’s kid or grandkid has the right temperament to own or lead a business.

Bailey says owners need to consider the temperament of their kids or younger employees when deciding to whom to pass the business after they retire. For instance, one son might have the knowledge to own the business, but he might lack a “people-person” personality, which could hurt the business.

“[Propane Resources] helped one retailer with its website right after a younger-generation owner took over,” Bailey says. “Not long after we made the website, the younger-generation owner called me and said, ‘You need to take the phone number off my website since I don’t want to talk to customers.’ When we asked him why, he said he wasn’t a people person, which is not a great fit for the propane industry.”

Bailey also recommends owners discern maturity levels in their kids and younger workers to determine who would make the best owner after they retire. He says owners should consider who would be most ready to lead at the time of their retirement.

“Be objective with this,” Bailey says. “I see a lot of people consider maturity subjectively as opposed to objectively.”

Propane equipment distributors have similar experiences to retailers in succession planning. Randy Rutherford, president of Rutherford Equipment, says his company got lucky when it was able to position his son, Mike, in a leadership role. Randy says Mike had the right personality, interest and maturity level as soon as he graduated college to take on a vacant role at the company as a manager.

“We were expanding a product line – gas grills and fireplaces about the same time I graduated,” Mike says. “Fortunately, I loved to grill and cook, so this sparked my interest. I was glad to join my dad back in the business.”

Next generation

Research shows that about 36 percent of all workers in the United States are between the ages of 20 and 34 – the millennial age group.

According to Nicole Lipkin, psychologist and business leadership consultant who co-authored “Y in the Workplace: Managing the ‘Me First’ Generation,” that figure will likely rise to 46 percent by 2020.

According to Propane Resources, millennials make up about 23 percent of the propane industry’s workforce. The company reports most owners in the propane industry are baby boomers, between the ages of 50 and 70, and most workers entering the industry are millennials.

Bailey says some disconnect exists between the two age groups, creating problems developing a family business’ succession plan.

“I see a lot of the older generation doesn’t feel respected when younger people come in with ideas,” Bailey says. “They’ll say to them, ‘You don’t understand – I built this company, and what we’re doing now works.’ Then younger generations retort, ‘Well, you need to respect times are changing and that you need to embrace social media and online presence – I can help with that.’ Yet it’s hard for the two to come to a meeting of the mind and agree.”

Propane Resources also reports that millennials are a much more tech-savvy generation, which comes to the workplace as a blessing and a curse.

Tamera Kovacs, a Propane Resources consultant, says this generation’s knowledge on technology can speed processes and potentially save business money. Yet she says technology also causes that age group to struggle with one-on-one communication and problem solving, both of which are important skills in the propane industry.

Although the situation seems futile, Bailey says older- and younger-generation workers can come to an agreement by choosing to learn each other’s strengths, weaknesses and general personality traits.

“Figure out the personalities of the different generations, and you might see eye to eye easier,” he says.

Lipkin’s book also reports that the future-generation workers tend to seek more flexibility at their jobs. She recommends workplaces try to provide future generations with flexibility in scheduling or vacation time to create the best outcome for the company.

What kills businesses?

Retailers and experts shared insight on what types of problems they think tend to cause family businesses to fail.

Keeping score: Malcolm Barrett, owner of Barrett’s Propane, says family members can’t “keep score” of “who got more time off” or “who makes more money” or “who got promoted fastest” in a family business. Barrett says it’s best to put those disputes aside and only worry about what is best for the company as a whole.

Making a plan too late: Several retailers and experts agree that it is not wise to wait until just before retirement or death to make a succession plan.

Assuming the value of the business: A North Carolina propane retailer, which wished to remain anonymous, says retailers cannot assume their business value based on gallon sales. For a more accurate figure, the retailer says to seek outside valuation from a consulting company, especially when estate planning.

Passivity: Mark Bailey, CFO of Propane Resources, says passivity in relationships can harm the family business. He says family businesses need to be objective and not worry about “hurting feelings” when deciding what will work best for the business. “The more open a family can be, the better off it will be,” he says. “If you can sit down and honestly discuss with everyone in the family about the business and get opinions out, the business is much more likely to survive.”

Forcing kids into the industry: Gary Papay, president of CK Business Consultants, says an owner’s kids should not be forced into the family business, especially if they are not interested. He recommends analyzing their interest levels, readiness and personality traits before handing the business down to them.

Not looking outside the box: The North Carolina propane retailer adds owners and next-generation owners need to have some outside experience or insight to help the company grow to get a better perspective. The retailer says looking at one’s own business can be biased. Seek outside input and ask questions about the business so it might grow. Do not be afraid to take input from younger generations, especially if they researched their suggestion.

Traits of the generations

Each generation is a product of its environment and the prior generation. When creating a succession plan, owners need to consider traits of people coming into the business. Here are some traits that come with each generation of workers:

Traditionalist – Born between 1925 and 1945

Strengths: Loyal, patriotic, conservative, thrifty

Weaknesses: Avoids conflict, doesn’t adapt to change

Baby boomer – Born between 1946 and 1964

Strengths: Competitive, career-focused, confident

Weaknesses: Dislikes conflict, judgmental, workaholics

Gen X – Born between 1965 and 1980

Strengths: Independent, adapts to technology changes

Weaknesses: Cynical, dislikes authority and rules

Gen Y – Born between 1981 and 1995

Strengths: Cyber literate, realistic, values individuality

Weaknesses: Dislikes menial work, lacks people skills

Source: Propane Resources research