Propane’s role in improving health, environmental standards

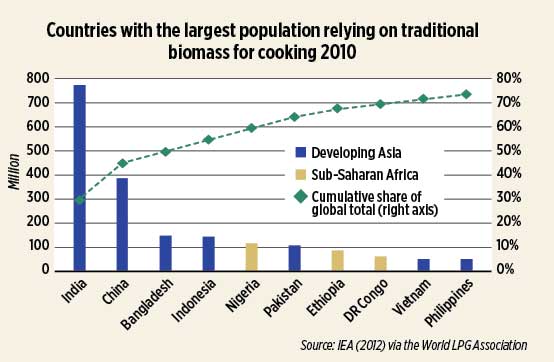

In India, Indonesia, China, parts of Africa and developing nations around the world, many women are spending hours every day cooking over flames fueled by wood, charcoal, animal dung or kerosene. In order to feed themselves and their families, they are exposed to deadly air pollutants produced by these fuels.

About 2.9 billion people still cook using biomass as fuel. Propane is a way to move away from this practice. Photo courtesy of the World LPG Association.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), people in households that use solid fuels for cooking make up 40 percent of the world population. That means about 2.9 billion people are exposed to indoor air pollution every day.

The exposure results in the premature deaths of an estimated 4 million people annually from lung cancer, cardiovascular disease, pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, according to the World LPG Association (WLPGA). The majority of people affected are the poorest members of developing nations.

Women and children have a higher risk of health complications due to indoor air pollutants, as they spend the most time in and around the home. Burning solid biomass – organic matter produced from plants and animals such as wood, charcoal or animal dung – for fuel also contributes to deforestation, soil degradation and global warming.

Fueling change

An initiative, started by WLPGA, is hoping to change all of that.

The Cooking for Life campaign was started in 2012 with the goal of transitioning 1 billion people from cooking with traditional fuels to clean-burning propane by 2030. According to the association, this will prevent 500,000 premature deaths a year and save about 6.6 million acres of forest for every 268 million households that convert.

According to WLPGA, Cooking for Life convenes governments, public health officials, the energy industry and global non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to expand access to propane and bring modern alternative fuel to people who need it most. The campaign also works to increase public awareness about how traditional fuels negatively affect everyday life among the world’s most vulnerable.

The campaign was developed to coincide with a focus put on clean cooking in the development community. According to Michael Kelly, deputy managing director and director of market development for WLPGA, there was a lot of recognition about the dangers of cooking over biomass and household air pollution.

“The World Health Organization had a newfound focus on this issue and our former president, Kimball Chen, was the driving force behind creating Cooking for Life as a platform for the LPG industry to participate and use initiatives launched by the [United Nations], NGOs and the World Bank,” Kelly says.

This campaign is coming at an important time. Kelly says there’s a recognition that society should be better stewards of the environment, and having millions of people cook on wood or charcoal three times a day every day is simply not good for the environment.

The initiative is also good for the propane industry, he adds. Retailers supplying these areas benefit from an increase in business and, globally, it is a PR victory to have propane be seen as one of the better solutions to an age-old problem. Even in the U.S., retailers can point to this initiative as a way to promote their fuel as doing good and modernizing life in developing countries.

Doing good

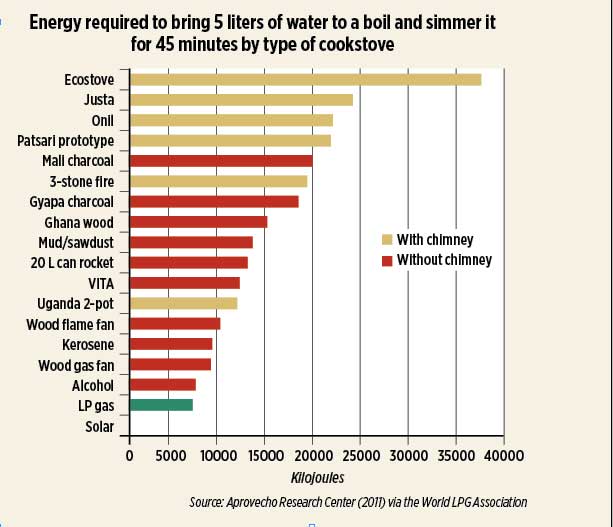

While some renewable energy systems are adequate, propane is an ideal clean-cooking fuel for several reasons. It is easily turned on and doesn’t smolder after it is turned off. It heats quickly and efficiently, and uses less energy to boil water than biomass, kerosene or alcohol. Most importantly, it is clean and portable.

The health benefits of switching to propane are numerous. Propane produces virtually no particulate matter, and compared to other fuels it has low emissions of carbon monoxide. Therefore, households that switch have lower air pollution levels and suffer fewer pollution-related health issues. These are also the reasons why it is good for the environment.

The goal of the campaign is to transition 1 billion people from using traditional fuels to propane by 2030. Photo: iStock.com/PisitBurana

According to WLPGA, other health benefits include improved quality of life as a result of less human suffering, a reduction in health-related expenditures, the value of productivity gains that result from less illness and fewer deaths, and lower risk of kerosene poisoning.

Women and girls also face health and safety risks associated with fuel collection, according to WHO.

“In some countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, women and girls spend four, five, six hours a day looking for wood, and that’s when they’re attacked, and they’re raped, or they’re bitten by snakes,” Kelly says.

Fuel gathering also places significant constraints on available time for education, rest and income-generating activities, WHO says. When they don’t have to look for fuel, women and girls can spend that time in more productive ways. Additionally, because propane is more efficient, overall cooking time goes down, further adding to the time savings.

“One of the things women in Indonesia appreciated most was the time savings,” Kelly says. “The mothers said they could sleep an extra hour a day, which is very important. … They could have a small business or send a child to school.”

When women in India switch to propane, they have more time to take care of themselves, their children, their households and to pursue their own interests such as stitching or visiting with friends, says Rachna Yadav, an independent Indian Oil distributor, in an interview with WLPGA and Exceptional Energy.

Encouraging the switch

Between 2007 and 2012, there was a program to switch Indonesians from cooking with kerosene to propane. Though it was before Cooking for Life was launched, this was the first time WLPGA supported a country doing a large-scale switching campaign, Kelly says. Seventy-five percent of Indonesia’s population has switched to propane, according to WLPGA.

Since the campaign’s launch, India has seen a major transition. IndianOil, an Indian state-owned oil and gas company, is working to make every household in every village in India smoke free, according to WLPGA and Exceptional Energy. In India, about 594 million people – just under half of the total population – now use propane, WLPGA says.

India has many innovative techniques for encouraging propane use, from offering small cylinders to subsidy systems using biometric cards. As the fuel has become more popular and accessible, many of them have spilled over to neighboring countries such as Bangladesh and Myanmar.

The campaigns to encourage switching to propane, and those who lead them, vary by country. In India, the government is the driving force behind the push, with the prime minister leading the charge, while in Indonesia the main oil company was the major implementer.

According to Kelly, no matter how the transition is being encouraged, appropriate laws and adequately enforced regulations are the single most critical factor in whether widespread access to and use of propane can be achieved and sustained for the long term.

“It does take recognition at the national level to address the problem,” Kelly says. “In Mozambique, where we did a workshop last year, something like 80 percent of the country cooks on charcoal and the country is being deforested at an accelerated rate and so the government has outlawed the transportation of charcoal … so that led to a spike growth of the LPG industry.”

In the 1980s, the Brazilian government encouraged the use of propane to stop the destruction of the rainforest. Though the government didn’t do it democratically, Kelly notes, it put a subsidy in place to use propane and now 90 percent of Brazilians work with propane in their homes. Brazil currently has one of the biggest, most dynamic propane markets in the world, Kelly says.

Acknowledging problems, finding solutions

Infrastructure is one of the major barriers to accessing fuel. In some countries, it is difficult to deliver and store propane. The population in remote, rural areas isn’t always large enough to support the market, so by the time the cylinder gets there it’s too expensive, Kelly says.

There are solutions to the problem, however. Kelly has been to a remote village in the Amazon where they brought in cylinders on boats and distributed to villages on horseback. Community kitchens are another innovative solution.

“You have a house in the middle of a village and people come and pay for 15-minute increments to cook,” Kelly explains. “It’s set up through microfinance and organized by the chief or head of the village and it teaches people to cook on LPG and it’s been quite successful in some communities in Asia.”

The challenge, though, is being realistic about the commercial sustainability of bringing propane to poor communities.

“LPG is simply not a solution for the poorest of the poor in these places,” Kelly says. “Maybe in these places they use biomass cookstoves in efficient ways until there is enough customer base for propane to appear.”

The financial feasibility of affording propane cookstoves and fuel is a challenge. Though governments often subsidize the purchase of propane or cookstoves, it isn’t always enough.

Andrew Simons, assistant professor of economics at Fordham University, worked in developing nations in Africa studying the barriers to accessing clean-cooking technology. His work centers around efficient charcoal and wood-burning stoves, but many of the same economic principles apply to propane.

“Some people would say poor people don’t adopt these cooking technologies or any technologies because they don’t have information about it; they don’t know about it,” Simons says. “Other people will say it’s because they don’t have liquidity. So, we actually tested that out.”

Many individuals know about the benefits of cooking on propane. It’s simply that active financing upfront blocks the purchase of fuel or a cookstove. Photo courtesy of the World LPG Association.

The team shared four different marketing messages about the cookstoves. After being exposed to the messages, participants wrote down a bid for what they would pay for the stove. This was done twice, once with cash and carry (paying for the stove outright) and once with a payment plan of four equal weekly payments.

According to Simons, across the four marketing messages there was no difference in average willingness to pay or in bid. However, when participants were extended the option to pay over a period of time, the willingness to pay jumped 40 percent.

“This would be an argument that it’s not that people don’t know about the benefits of these stoves, or that they don’t know they should want them,” Simons says. “There is demand there. It’s just the liquidity or active financing up front that’s blocking the purchase. It’s a financial constraint rather than an informational constraint.”

In many countries, there are still occurrences of stove stacking, where a household will use an alternative fuel stove, but won’t completely switch over from biomass. Stephen Harrell, a Ph.D. candidate at U.C. Berkeley, is conducting a study to determine how to incentivize households to fully abandon biomass.

In India, low-income households are able to obtain a stove and their first cylinder from a government subsidy, but they continue to use old biomass cookstoves for certain tasks or cooking needs. One major barrier to exclusive propane use is the gap in time between when a household’s propane cylinder becomes empty and when they receive a refill.

“If you own only one cylinder, when it runs out you have to get a refill,” Harrell says. “There is a delay in that time and there’s no way any house can use gas if they’re waiting on that.”

Upper- and middle-income homes always have two cylinders, so there is a constant supply of propane, Harrell explains. He and his fellow researchers are piloting ideas – including free trials or options to pay over time for a spare cylinder – for getting low-income households to adopt this practice. The team is also studying the effect of removing the biomass stoves altogether.

“It’s an exciting solution because in some higher-income households they have electric stoves, but the majority are gas,” Harrell says. “This is one cool technology that, thanks to the Indian government, allows people of all incomes to have the same technology to cook.”

Harrell sees this work as important not only because it improves public health, but also because it creates opportunities for people who would likely have very few otherwise.

There is too much inequality in the world, he says. Addressing issues like these give more people, especially women and children, opportunities to use their skills and abilities, and enjoy life.