Crude prices continue to fall due to COVID-19, failed negotiations

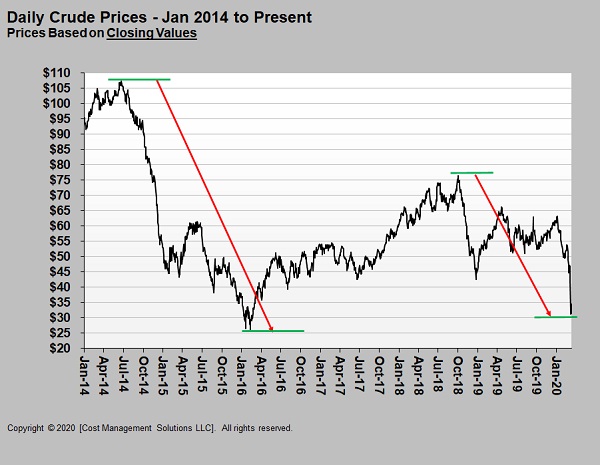

On Monday, Feb. 9, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude’s price fell to an intraday low of $27.34 before closing at $31.13. It had closed the Friday before at $41.28, constituting a nearly 25 percent drop in value in one day. Many have called since that day asking if the price of crude can go any lower. Our answer is, yes, it can.

In today’s Trader’s Corner, we will look at the reason for the drop and why we believe the price could go even lower. To provide a proper justification for our answer, we need to study a little crude history. Let’s begin in 2008 with the events that have led the crude market to where it is today. This will provide the proper context for why crude prices could go lower.

On July 3, 2008, WTI crude reached a record high of $145.29 per barrel. Crude had risen to such lofty prices because global demand was outpacing available supply. Emerging economies such as China and India with their massive populations were demanding more crude than the world could supply. For the first time, the United States was not the only big export destination in town. It was a heyday for crude exporting nations such as those belonging to OPEC.

By the time crude reached its record highs, U.S. crude production was below 4 million barrels per day (bpd) at a time when the United States was demanding over 20 million bpd of petroleum products. The high prices allowed high-cost crude production from shale formations to become justifiable. At the time, it took $60 per barrel or better for a well drilled in shale formations to be economically viable, compared to $5 per barrel or less for conventional wells in places like Saudi Arabia.

As U.S. crude production began to grow from shale production, OPEC trimmed its production to make room for the new supply to support prices. By January 2014, U.S. crude production had more than doubled to over 8 million bpd. OPEC began to see its strategy of reducing its production to make room for U.S. supply was counterproductive. They were essentially creating their own competition.

By November 2014, U.S. production had reached over 9 million bpd, and the price of crude had fallen below $80 per barrel. OPEC, led by Saudi Arabia, had seen enough. It announced it would no longer cut production to support prices and instead would increase production to reclaim market share. It concluded it could put U.S. shale producers out of business given the wide discrepancy in production cost. By then, U.S. shale producers had improved technology and techniques such that they only needed about $50 per barrel to break even, and that number was falling as economies of scale improved. Today, that break-even number is down to $40 per barrel.

Further complicating the situation for OPEC was that on average the group needed $102.59 per barrel of crude to pay for all of the government programs they had instituted that were dependent on crude revenues. Even heavyweight Saudi Arabia needed $86.10 per barrel of crude to balance its budget. Still, OPEC forged ahead with this policy.

U.S. producers held on longer than expected, and the price of crude fell all the way to $26.21 by Feb. 11, 2016. Though most U.S. shale companies were hanging on by a fingernail, producer nations were suffering the most. Saudi Arabia stopped the drop in crude prices at that point by simply saying they would once again control production if they could get non-OPEC producer nations to cooperate with them.

Crude prices recovered to around $50 per barrel, saving many U.S. shale producers and helping other producer nations gain some control over burgeoning budget deficits. But it took time to form an alliance between OPEC and other producers. It was not until October 2017 that a group of 24 producer nations including OPEC, Russia, Mexico and Kazakhstan, among others, agreed on a plan to cut 1.2 million bpd from their combined production beginning Jan. 1, 2018. Crude dipped below $45 per barrel by the time that group had announced its plan. Crude then recovered to as high as $75 per barrel. Growing U.S. production once again became the nemesis. Growth in U.S. production backfilled all that OPEC+ was removing from the market, which particularly upset Russia. By 2019, U.S. production had reached 13 million bpd, keeping prices capped at between $50 and $60 per barrel.

OPEC+ was forced to cut another 500,000 bpd of production at the beginning of 2020 to avoid a major oversupply in the first quarter. The plan was to eliminate that cut at the end of March. But those plans were thwarted when the COVID-19 virus came to light. An OPEC+ technical committee recommended on Feb. 1 to extend the 500,000-bpd cut through the end of the year and cut another 600,000 bpd through June. Russia balked, and that recommendation was never implemented. The impacts of the COVID-19 virus were soon wreaking havoc on global crude demand.

Leading up to an official OPEC+ meeting that was to conclude on March 6, OPEC was recommending the 500,000-bpd cut originally intended to end March 31 be extended until the end of the year. OPEC also recommended the additional cut proposed in February be raised from 600,000 bpd to 1.5 million bpd and last through the end of June.

The plan was that OPEC nations would cut 1 million from their production and that Russia and other non-OPEC producers would cut 500,000 bpd. Much to the chagrin of Saudi Arabia, Russia rejected the proposal. That resulted in the 25 percent drop in crude prices on March 9.

In the aftermath, Saudi Arabia essentially announced that OPEC+ was non-functional and producers were free to raise production to whatever they wished starting in April, basically the same decision made in November 2014 that eventually drove crude prices to $26.21 per barrel.

They also said they were raising production from 9.7 million bpd to 12 million bpd, increasing their production capacity from 12 million bpd to 13 million bpd, lowering their sales price by $6 to $8 per barrel and going after Russia’s market share. Suddenly, the producer allies were enemies. On Friday, it was revealed that Saudi Arabia was flooding Europe with $25 per barrel crude in a direct attempt to supplant Russian supplies. Russia has responded by increasing its production and will no doubt lower prices to compete.

At a time when crude demand growth has dramatically slowed or perhaps is going negative, with the market already oversupplied and inventories high, two of the world’s biggest producers are now flooding the market with new supply. Other producers in OPEC+ will likely respond by raising production to try to offset lost revenues. It is likely that only U.S. producers will respond by cutting capital spending as a result of these developments, but it will still take awhile to affect U.S. production.

If Russia and Saudi Arabia come back to the negotiating table, the price of crude could rise sharply. However, on the present course, it is very easy to see crude falling below the $26.21 low set on Feb. 11, 2016, and continuing lower. Between demand destruction from the COVID-19 virus and more supply hitting the market, it seems hard to imagine another outcome.

Many producers are not making money at this crude price, especially those in the United States. We can also be assured that OPEC nations and their once producer allies will all be struggling to fund government budgets due to lower oil revenues. Something will have to give. But the timing of that something is unknown. Until it is known, the market is almost certain to punish crude prices. As low as crude prices are, they can go lower, in fact, much lower.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how Client Services can enhance your business at (888) 441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.