Explaining the basis, catalyst of historic crude price drop

History was made this past week when May West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude fell to negative $40.32 per barrel before closing at $37.63. Prior to this occurring, crude had never traded in negative numbers. In today’s Trader’s Corner, we are going to explore how and why this happened.

The foundation of the event was set in motion by the COVID-19 pandemic. As we are all aware, governments have asked citizens to shelter in place to avoid spreading the virus at a rate that would overwhelm available medical services. The result has been a dramatic decrease in global crude consumption. Most estimates have demand down 20 to 25 million barrels per day (bpd) from pre-pandemic levels.

It was a dramatic shift in demand, and the supply side has been too slow to react. The result has been extreme oversupply that has most available crude storage nearing capacity. For example, the major U.S. trading hub of Cushing, Oklahoma, where crude futures contracts are settled, has 76 million barrels of storage. Working storage is probably even less.

Last week, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported Cushing inventory at 59.741 million barrels, up 4.776 million barrels for the week ending April 17. At that rate, Cushing storage would be at max storage in just over four weeks. That would be during the week of May 11. Industry analyst Genscape pegged inventory at over 60 million barrels and said inventory had increased 9 million barrels during the week of April 17. At that rate, inventory may already be nearing capacity.

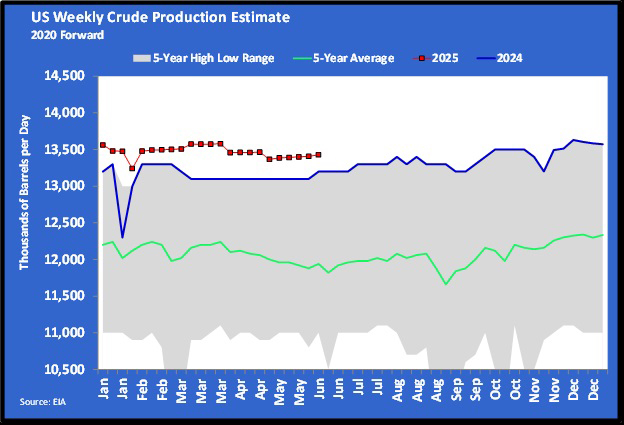

In its last report, the EIA estimated that U.S. crude production was at 12.2 million bpd, which is down about 900,000 bpd from its highs earlier this year. However, U.S. refinery throughput is down 4.127 million bpd since last year at just 12.456 million bpd and falling. Meanwhile the United States imported about 2 million bpd more than it exported. The United States was producing or importing 1.747 million bpd or around 12.2 million barrels per week more than refinery demand. That much crude moved to storage. It is easy to see that at that rate, storage at Cushing and other storage locations will fill quickly.

That’s the basis of the problem, but the expiration of the May crude contracts requiring players to settle all outstanding contracts was the catalyst that drove prices into the negative.

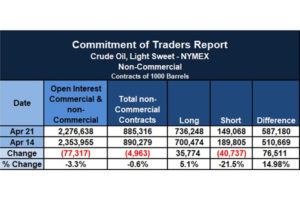

The table to the right shows data provided by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission on crude futures contracts for April 14. It shows there were 2,353,955 commercial and non-commercial crude contracts in play. A contract is 1,000 barrels. A commercial contract is held by someone that is in the crude business in some way. A non-commercial player is not in the business but is speculating. This could be hedge funds, banks and similar businesses. There were 890,279 of those contracts in play on April 14. Some of those would have been for May crude.

When a non-commercial player takes a “paper” position on a commodity, they never expect to physically take delivery of the crude they bought. In fact, they probably don’t have the ability to take the physical product. They plan to sell the position to someone that can take the barrels at a profit before the contract expires. Of course, if prices fall, the position would be sold at a loss – such is the nature of speculation. The assumption is there will be some commercial player that can buy the position, which has always been the case in a liquid (highly traded) market like WTI crude.

But the crude market has become illiquid as there are too many sellers (longs trying to close) and not enough buyers (those needing crude for use or storage). Refiners don’t want it; they are reducing runs and U.S. storage facilities are nearly full. Anyone with the capability to take barrels knows there isn’t enough demand or storage to take what is on the books, so those longs are literally paying to get the few players left with the ability to take barrels.

Some of the longs are trying to roll the positions, which means they would sell the May and buy a future month. That keeps the out months higher than the current or front month. However, if the fundamental situation isn’t resolved, prices in future months will go down. Those rolling barrels could find themselves in the same position at the end of next month.

There is an exchanged-traded fund known as the United States Oil Fund (USO) that got much of the blame for the fall of May crude. Supposedly, the USO has made policy changes that may mitigate the problem in the future. However, the only sure way to avoid the possibility of a repeat is for more U.S. production to be shut and less imports taken.

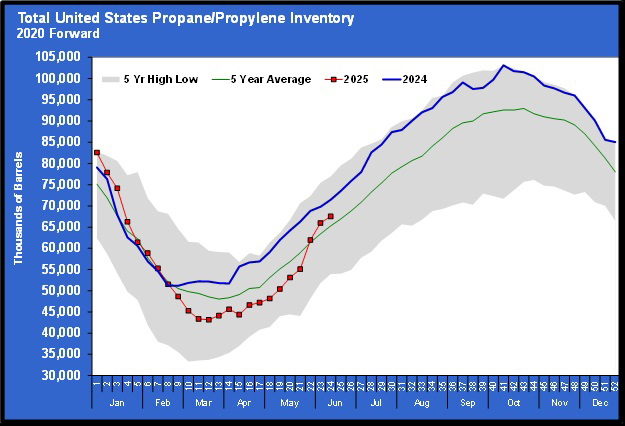

That is going to result in less propane supply. Propane demand has remained fairly strong through COVID-19 for various reasons. A reduction in oil and gas production is going to support higher propane prices as long as propane demand holds up.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how Client Services can enhance your business at (888) 441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.