Part II: Russia/Ukraine conflict to intensify ‘energy war’ this winter

Trader’s Corner, a weekly partnership with Cost Management Solutions, analyzes propane supply and pricing trends. This week, Mark Rachal, director of research and publications, elaborates on the challenges of meeting customer expectations this winter.

In last week’s Trader’s Corner, we used the phrase “Winter is coming,” which was used in the HBO series “Game of Thrones” as a warning that tough times are ahead, and one had best use the relatively good times presently to prepare for those tougher times if they want to survive. Our focus this week is how the West has used the time since the war in Ukraine began to prepare for this upcoming winter. As tough as the war has been on the global economy by causing a sharp rise in energy and food prices, what has occurred thus far pales in comparison to what could happen this winter.

Russia continues to hold tremendous leverage over Europe because of Europe’s dependence upon it for energy. The greatest dependency is natural gas. Russia reduced supplies to Europe this summer to just 20 percent of normal, limiting its ability to store desired amounts of natural gas. Now, Russia has completely cut off natural gas supplies as winter nears. It is obviously using natural gas as a weapon of war to try to get Europe to end its support for Ukraine.

Moving natural gas by pipeline is relatively easy and efficient, and that is the advantage that Russia has created. Not only does it have abundant supplies, but it has a developed a pipeline system to deliver it to Europe. Other potential natural gas suppliers for Europe do not have that logistical luxury. The U.S. is among those that must liquefy natural gas and send it by ship to Europe. The facilities on both ends to liquefy and deliquefy are limited and take years to build. There was never going to be the chance to avoid the issues with natural gas for this winter save a resolution in the Russia/Ukraine war or capitulation by Europe in its energy war with Russia.

This situation is a creation of Europe’s own making. Socially and politically, it pushed elimination of its own hydrocarbon production far faster than it was able to replace it with alternatives. It did little to slow its demand for hydrocarbons. It just made itself feel better by getting that nasty old, planet-killing stuff from Russia. It is somewhat akin to those who have large houses on multiple continents who use private jets and yachts to move between them and then lecture everyone else on climate change.

That is why we find ourselves so frustrated by the lack of urgency with which the West has moved to reduce the leverage that Russia holds in the energy war. Until Friday, we had seen little change in policy or efforts in general to increase hydrocarbon production in Europe. On Friday, it was reported that Britain has reversed a decision it made in 2019 to end production in shale formations – finally, a decision made based on the realities of the situation.

Most other European efforts have seemed to be concentrated on areas with unreasonable timelines that have no way of addressing the situation until the war is probably over. In the face of all the terrible realities of depending on Russia for energy security, there is still a reluctance to think realistically. Europe has focused on reducing hydrocarbon use and finding other sources outside itself rather than increasing its own production. Anyone with a pencil and a notepad could have calculated that those efforts were going to be too little, too late.

We are not criticizing the desire to reduce hydrocarbon emissions to protect the environment. The desire to do it and doing it are different. Lowering one’s own hydrocarbon production and relying on another country to provide it without alternatives seems more a desire to be perceived as righteous than a real effort to save the planet. In fact, doing so actually increases energy consumption by necessitating more consumption in logistical efforts to move it from where it is produced to where it is consumed. Europe is not alone; we see the same dynamic in the U.S. If you really want to help the planet, produce the hydrocarbons needed as close to where they are consumed until you don’t need them any longer. Pushing the production off to others to make yourself feel better is wrong on many levels, and that is certainly manifested by what we are seeing in Ukraine.

Given the long timeline on addressing natural gas logistical issues, the opportunity for the U.S. to help Europe lies with crude and refined fuels. Our crude production when the war broke out was well below peak production. Therefore, we knew we had the infrastructure and capacity already in place to support more crude production. However, we warned that U.S. producers were going to be very hesitant to increase production unless it had firm commitments from Europe to take it. We don’t think those commitments came.

The U.S. government took the easy step of releasing huge quantities of crude from our strategic petroleum reserve. We provided the details on that in last week’s Trader’s Corner. But, beyond that, it has done little to encourage more energy production by policy or regulatory action. In fact, it has been the opposite. Most efforts have been to villainize the industry and accuse it of price gouging.

The release of crude from reserves would have been prudent if it were to give time to take other steps to increase production and the ability to export energy. Instead, it appears it was mostly politically motivated to try to get energy prices back down before the midterm elections. In fact, the releasing of reserves runs the risk of increasing crude prices long term once they end with no reasonable way to replace them.

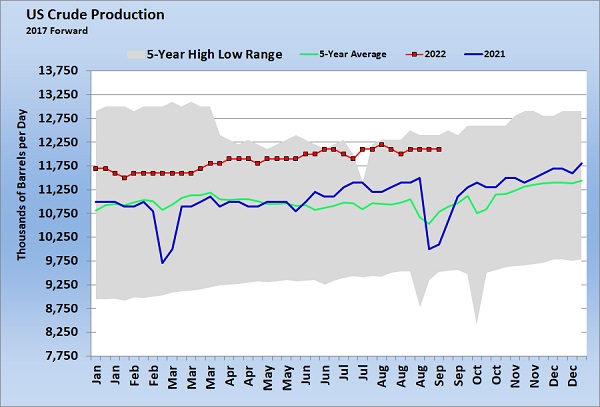

U.S. crude production is up this year over last. Production has averaged 11.868 million barrels per day (bpd) this year, and the most recent estimates by the Energy Information Administration are production of 12.1 million bpd. This year’s production is up 766,000 bpd over last year. U.S. producers have been very hesitant to try to take production back to its peak at 13.1 million bpd. Production averaged 12.304 million bpd during 2019 before the pandemic.

U.S. energy companies have completely changed their approach since the pandemic. It used to be all about increasing production. That is no longer the case. The focus is now on fiscal discipline. The efforts are to provide shareholder return and pay down debt. These are efforts that had to be done to try to attract investors once again. For years, U.S. companies poured all the profits back into the company to increase production. Investors were left out in the cold and companies became overleveraged. Then the pandemic came, and the financial sector took a major hit from loans it had made to energy companies. Investors pulled their money out, and most haven’t been coming back. Energy companies have been using the windfall from recent high prices to buy back and retire their own stock to keep stock prices supported rather than increasing capital expenditures.

It all makes sense because U.S. shale production with its high costs should have never been supplanting much cheaper traditional production in other countries. U.S. oil companies producing primarily from shale formation have learned that production at all costs only costs them. We are not surprised in the least that production has been slow to recover despite the high prices and great need in Europe. Without the governments of Europe or the U.S. encouraging production and providing guarantees, U.S. producers are making the prudent choice to maintain their capital discipline.

We find ourselves in a situation where the releases from strategic reserves will end in about 30 days. Our production has not increased enough yet to offset those releases. We have been exporting about 675,000 bpd of the crude from the reserves, and the rest was used at home to offset what we were getting from Russia before the government put an embargo on imports from crude and refined fuels from Russia. Right now, one must assume that Europe will get less of our crude when the reserves run out since our production alone can’t support the same level of exports. This is to say nothing about being high enough to replace reserves.

Next week, we will go into our crude import/export situation. Is the U.S. becoming less of a burden on global supply so that more can go to Europe? How are we doing increasing refined fuels production and capacity? Being able to send more refined fuels that are ready-to-use to Europe would certainly be a help, but have we increased our capacity to do that?

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how client services can enhance your business at 888-441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.