Farmer cooperatives meet multiple agricultural needs

Marketers of all sizes have probably looked at competitors, farm cooperatives included, with a resentful eye at one time or another. Some marketers will naturally argue that farm co-ops have an advantage serving the agricultural community, that they’re able to supply farmers with lower propane prices and that they’re pricing others out of farm delivery.

There’s no doubt winning over the farmers who are members of a co-op, or any customer for that matter, is a challenge. But better understanding a farm co-op’s role – how it functions, how co-ops have evolved and what their goals are today – can help to explain why many farmers gravitate to co-ops for their propane rather than buy through another marketer.

A little history

No two farm co-ops were founded for the exact same reasons, but many started because a need existed at one time for the local community of farmers.

Southern States Cooperative, for example, is the 12th-largest propane marketer in the United States. It did not, however, originally form because a need for propane existed. Instead, as the cooperative’s Terry McMahon says, Southern States came together because none of the seed suppliers in the 1920s sold seed that grew well in Virginia soils.

Members of the cooperative later developed a need for better access to fertilizer. So they put up their first fertilizer plant. Propane was introduced because a need developed, too, but Southern States, like most cooperatives, leverages its buying power for more than just better propane prices.

“It all comes back to what the customers need and if we can provide it,” McMahon says. “About the only thing we don’t sell to farmers would be large equipment like combines and tractors.”

McMahon adds that the farm cooperative concept dates back to 17th-century Europe. The concept came to the U.S. shortly after the Civil War, when the U.S. infrastructure was largely destroyed and land-grant universities were established.

“[Congress] was trying to come up with ways it could encourage more creation of engineering-type educations and agriculture,” McMahon says. “Later, Congress passed an act that established cooperatives as a good way for farmers to do business. Farmers wanting to get together to buy goods or services could do so without it being an anti-trust issue.”

Today, Southern States is made up of thousands of farmer members, and its stores are divided into three kinds. One is the private dealer who, as Southern States’ Lee Mitchell puts it, “sell our products under our flag.” Mitchell describes a second kind as “managed co-ops,” meaning the corporate Southern States entity manages the locations yet local co-op members are the owners. The corporate Southern States entity owns and operates the other locations.

“All three kinds combined, we have about 1,200 locations across the East Coast,” Mitchell says. “Only about 100 of those handle bulk petroleum.”

Focused beyond propane

MFA Oil, a farm cooperative and a Top 50 Propane Retailer like Southern States, has roots that date back to the 1920s. Propane has been a part of MFA Oil’s member business since the 1960s, and it will likely continue to be a part of MFA Oil well into the future.

But as farmer needs develop, so must cooperatives like MFA Oil. And so the Columbia, Mo.-based cooperative is making some unique investments.

“We’ve got the biggest biomass project in the country right now,” says Tom May, MFA Oil’s marketing director. “The farmer members are looking to see what’s out there that would be a benefit to them.”

MFA has specifically teamed with Aloterra Energy LLC to create MFA Oil Biomass LLC, which is leaning on Miscanthus giganteus, a perennial grass that can be pelletized and burned for heating. The argument can be made that pelletizing miscanthus as a heating source contradicts the propane part of MFA Oil’s business. But May says organizing a biomass company stems from its farmer members’ needs.

“We have customers who’ve switched to burning wood pellets,” May says. “So they’ve already made the decision that they can cost-effectively use another energy source other than what we’re providing.”

MFA Oil will continue to pursue growth for its propane business, as 70 percent of the propane it sells is to non-agricultural entities. But putting its members’ needs first – and in this case, pursuing the miscanthus opportunity is one way to meet those needs – is MFA Oil’s priority.

“We’re continuously trying to bring value,” May says. “There’s a better trust in the relationship, that you’re not just trying to sell me something to make a profit off of it. We’re a company that’s here to make money. But at the end of the day it’s about trying to find the right value for our farmer members.”

And the better the value, the better the financial return a cooperative’s farmer members will receive at year’s end. This goes not just for MFA Oil, but for the typical farm co-op as well.

“The difference between a farm cooperative and a non-farm cooperative business is we pay a refund, be it a portion of our profits, back to members,” says John Camp, who operates a Southern States location in Hopkinsville, Ky. “The portion can vary depending on what type of year we had and what percentage our board of directors deems to pay back.”

Four of LP Gas Magazine’s Top 50 Propane Retailers also appear on Rural Cooperatives Magazine’s latest Top 100 ag co-ops list based on annual revenue. A revenue of $25.3 billion makes CHS the largest ag co-op in the country. Its revenue is twice the size of the country’s second largest ag co-op (Land O’Lakes Inc.), and about the size of the second, third and fourth largest ag co-ops combined.

Opportunities on the farm

MFA Oil, like other propane marketers, would like to develop new market opportunities for propane, or revisit old ones on the farm. Two opportunities MFA Oil’s Tom May sees on the farm are lawn care and weed control.

“Lawn care is a farm-related, not-farm-related-type thing,” says May, MFA Oil’s marketing director. “Farmers typically have a pretty big yard on their property they have to take care of. So here in Missouri, with the Missouri Propane Education & Research Council (MO-PERC), we’ve really been working to expand into lawn care with the high price of gasoline that provides an opportunity to use propane.”

Weed control is another potentially big opportunity, May says, but the process to involve propane more widely is an evolving one.

“I think there is opportunity either at the expense of chemicals that continue to go up in price, or as farmers evaluate the safety and long-term effects of chemicals,” he says. “It’s kind of going through the knothole because right now there are a lot of organic folks who don’t have the acreage to make it worth investing in that sort of [propane-powered] equipment.”

Huge corn crop predicted

Propane marketers shouldn’t stray far from their farmer customers this growing season, not with one of the largest corn crops on record predicted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), possibly requiring the greater use of a propane grain dryer.

According to the Prospective Plantings report released on March 30 by the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service, U.S. farmers intend to plant 95.9 million acres of corn in 2012, up 4 percent from 2011. That would make it the largest corn crop since 1937, when 97.2 million acres of corn were planted. Farmers in Iowa, Idaho, Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota expect to set records for corn acreage in 2012.

The Propane Education & Research Council (PERC) says propane grain dryers help farmers gather and store their crops more efficiently. Two grain dryer manufacturers, GSI and Mathews Co., currently participate in PERC’s Farm Equipment Efficiency Demonstration (FEED) program, which offers agriculture producers a financial incentive for purchasing propane-fueled equipment and reporting performance data. Visit www.agpropane.com/feed.

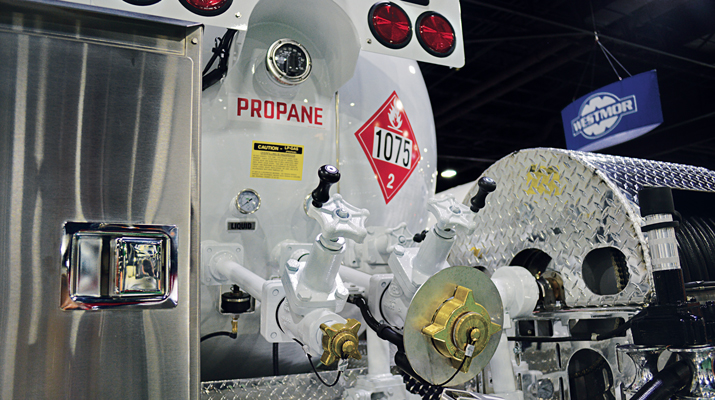

Photo above courtesy of Southern States Cooperative