Propane powers up amid growing US oil, gas production

Propane is often associated with space and water heating or as a fuel for buses and other fleet vehicles. A nontraditional application with potential for growth, however, is power generation.

An increasing amount of oil and gas is being extracted from energy-rich shale oil fields, from the Permian Basin in the Southwest to the Bakken formation in the northern United States and Canada. This includes propane as a natural gas liquid and gas associated with oil drilling.

Tucker Perkins, president and CEO of the Propane Education & Research Council (PERC), notes that shale oil and gas fields, including the Permian Basin, have rapidly evolved over the last 20 years into oil and gas production powerhouses due to hydraulic fracturing – also known as fracking.

“Fast forward to today: It’s this wild world dominated by oil and gas companies seeking production where there’s no established power grid,” Perkins says. “Somebody has to produce power.”

Propane serves multiple needs for companies working in these oil and gas fields, taking the place of electricity, which is expensive to bring to these remote worksites. In addition to heating water, offices and housing for workers, propane fuels generators to power the wells, water pumps, rig heaters, camp heating and lighting at night, since the camps operate 24/7.

Propane is also sometimes injected instead of water and sand into shale formations to crack them and extract gas to save water resources.

It is also important to note, however, that many facilities are consuming the gas that they produce, and it is unclear how much odorized propane they are purchasing from marketers. Moreover, the transitory nature of the production campsites that require power generation means that they are a relatively impermanent market.

Despite these challenges, this market offers an emerging opportunity, even if competition from other fuel types persists. The fueling hurdle is expected to lessen in the coming years based on growing demand and the advantages propane holds – readily available, portable, safer and cleaner – over other fuels, especially as more demand from homes, vehicles and data centers is expected to strain the electric grid.

Production data shows uptick

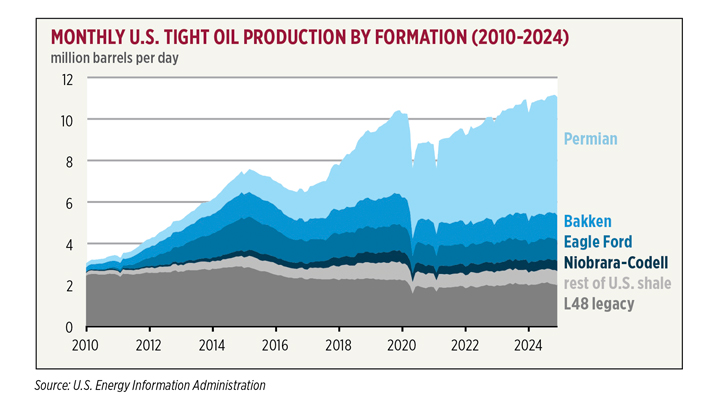

Recent figures from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) show growth in crude oil and natural gas production, particularly in the Permian Basin, which straddles Texas and New Mexico.

In the Lower 48 states, according to the EIA, onshore crude oil production has more than tripled since 2010. This growth has been driven by an increase in tight oil production in the Permian region. Tight oil, a subset of shale oil, is produced from petroleum-bearing formations with low permeability that requires fracking.

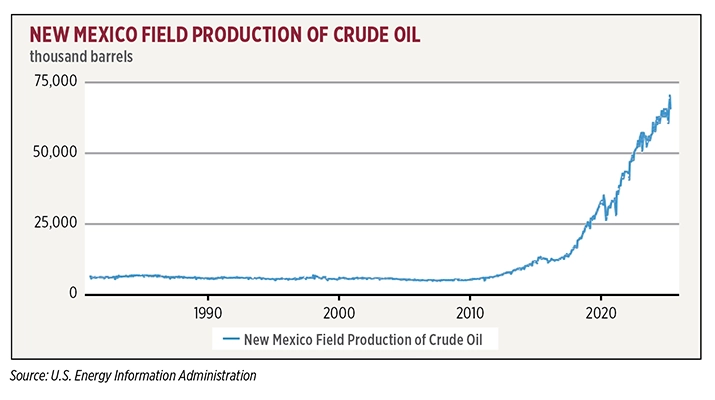

New Mexico alone, which is home to part of the Permian and the San Juan basins, saw monthly crude production steadily rise from a little over 5,000 barrels in 2010 to more than 70,000 by 2025, according to the EIA.

Tom Clark, executive director of the Rocky Mountain Propane Association, Colorado Propane Gas Association and New Mexico Propane Gas Association, says that fracking business in New Mexico has increased considerably over the last 15 years.

Energy production hubs in the state include part of the Permian Basin, which primarily produces crude oil as well as some natural gas, and the San Juan Basin, where coal and natural gas are produced.

All of that propane, however, may not be odorized. Companies may be recapturing some of it and pumping it back into the ground as part of the fracking process, Clark says.

Clark points to the possibilities of some non-odorized propane being sold in the oil and gas markets or of companies consuming the natural gases that they are extracting. He adds that he has not seen increased propane gallon sales reported in New Mexico.

“I’m wondering how much of the gas in these oil fields that’s being consumed for heat and electricity is produced right there on the spot and never actually goes through the sales cycle,” Clark says. “They captured it themselves and reused it for their own processes.”

Numbers from PERC’s annual gallon sales report may bear that out. In 2023, U.S. propane retailers saw an 8.6 percent decline in odorized propane from 2022 reported gallon sales, though the year’s total still came in near the industry’s 10-year average (9.04 billion).

While Clark says he hasn’t seen a bump in propane sales in New Mexico, the rise in labor and equipment needed for oil and gas fields is likely driving a need for electricity, heat and hot water, which could potentially translate into higher propane sales.

Dueling fuels

About five years ago, diesel was thought of as the exclusive fuel source for generating power, Perkins adds, but today, propane and natural gas are the primary competing sources.

Propane is now thought of as a primary fuel, Perkins explains, mainly because engines used in power generation that are powered by wellhead gas can also run on propane. The fuel comes in handy when there isn’t enough wellhead gas available to run the engines.

Additionally, propane holds a storage advantage over diesel and natural gas. Operators can store relatively large quantities of the fuel without the danger of leaks or spills.

Still, Clark notes that a lot of heat is required to extract natural gas and separate the liquid from the gas. If natural gas prices are higher than propane prices, operators will use propane as the fuel source in the separation process and vice versa.

Fuel prices have fluctuated over the years. When they were up, customers were more concerned with quick delivery than price. Now, though, oil and gas companies are increasingly more price-conscious and environmentally conscious, Perkins says. That makes propane’s attributes – versatility, affordability, portability, easily storable – even more attractive.

“Oil companies, gas companies think about their image, and, because they have to report all these emissions, they think about their emissions,” Perkins says. “Any time they have a chance to use a cleaner fuel, it’s a big benefit to them. … [That’s] why a lot of times, it’s the first choice.”

Nontraditional use cases

Meanwhile, some propane companies based in North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming and Texas specialize in supplying fuel to these oil fields, albeit under a business model that differs from traditional residential delivery service.

“These are usually larger truckloads and more of a wholesale-style delivery,” Clark says.

Some of the crude oil being produced in fields in this area has a higher wax content, Clark says. That’s why, he adds, he is seeing increased propane consumption for hot oilers – a hot oil rig that heats water to remove wax from oil wells – in fields in Wyoming and Utah.

“Some of these hot oil rigs will have a 3,000-gallon bobtail barrel on the back of their rig,” Clark says.

Conversely, one Wyoming-based hot oil rig business that was buying propane to clean oil wells transitioned from selling to the rigs to moving into the retail market.

“These oil-field businesses are buying a lot of propane; they’re buying it at good prices because they are consuming so much,” he adds. “They realize that there’s an opportunity to sell that same propane that they’re buying for their own consumption to their community. There [are] margins to be made [on] the retail side of the business.”

Technology-driven growth

Also opening this market for propane, Perkins says, is a technological evolution that developed simultaneously on three fronts: oil and gas companies, equipment such as engines designed to meet increased demand, and leasing companies.

The capabilities of the engines being used to power generators have advanced with the availability of engines in the 350-kilowatt range from companies like Guascor Energy and Jenbacher. The propane industry has been working for the last 10 years to bring to market propane engines that are comparable in quality, durability and size to compete with diesel. Meanwhile, the supply chain has also improved alongside oil and gas production growth in the United States.

“The suite of engines matured to the point where they were of the right size and durability and became available for these markets,” Perkins says. “It has taken probably five years for the supply chain to catch up to the demand as well.

“It starts with having an engine that works,” he adds. “It finishes with having a leasing or a rental company that has those engines in stock and understands how to maintain them.”

LP Gas also spoke with other companies that build generators for the oil and gas market, among other applications, including Dragon and Evergreen Mobile Power.

“The generators that we actively have in the market are being used at man camps in West Texas for the oil and gas industry,” says Steve Stump of Dragon Power, noting one Texas-based propane marketer that prefers to keep its activity in the Permian proprietary.

Propane powers up

Propane may not have been considered as the top fuel for prime power generation in the commercial or industrial world in the past due to diesel dominance in powering engines and generators. Now that there are equivalent propane engine offerings on the market alongside increased oil and gas production, which signals greater demand for power generation, propane is positioned to solve a broader electricity production shortage in a variety of industries.

“Power is getting more expensive, it is getting less reliable, and we’re seeing this movement to propane power generation across the country,” Perkins says. “[It’s] not confined just to the oil fields, but in commercial and industrial facilities, even residential developments.”

Perkins adds that the world is becoming more reliant on energy from the United States just as it experiences a natural gas supercycle that will lead to record amounts of propane production and keep prices stable. That’s a boon for suppliers and customers.

“It’s not unique,” Perkins says. “This is the early days of a great rebirth of propane used to provide power.”