Renewable propane may be the key to the industry’s future

REG Geismar is a 75-million-gallon nameplate capacity renewable diesel biorefinery located in Geismar, Louisiana. REG Geismar converts waste fats and oils into renewable diesel, renewable propane and renewable naphtha. Photo courtesy of Renewable Energy Group

On a molecular level, renewable propane is identical to the traditional propane used by retailers and consumers across the country. But on a national scale, renewable propane is completely different and pushes the propane industry and its fuel into the energy conversation for the future.

About four years ago, Joy Alafia, president of the Western Propane Gas Association (WPGA), reviewed the WPGA’s strategic plan to see what was happening in the environment, the marketplace and legislatively. “It was painfully obvious” that if propane wanted to compete in western states in the future, the fuel needed to become cleaner, Alafia says.

In several states, including California, zero carbon or close to zero carbon emitting fuels are quickly becoming the norm. Without a renewable component, propane is excluded from that list.

“From a technical standpoint, renewable propane is a byproduct of the renewable diesel process,” Alafia says. “It is about sustainability, so being able to have a propane fuel that is generated from a renewable source. In the case of renewable propane, you are looking at propane being produced from either vegetable oil or beef fat.”

If a refinery produces renewable diesel, it has the ability to produce renewable propane. Photo: iStock.com/halbergman

Renewable propane can be used in the same applications as conventional propane because they both have the same molecular structure. The difference lies in renewable propane’s production sources: vegetable oils, animal oils and other triglycerides.

“That is one of the beauties of it,” says Tucker Perkins, president and CEO of the Propane Education & Research Council (PERC). “Renewable propane will behave exactly like propane in any of the combustion categories.”

But developing this renewable component is what some strongly consider crucial for the future success of the industry.

In a guest column for the January 2018 edition of LP Gas magazine, Stuart Weidie, president and CEO of Blossman Gas, argues that if propane wants to brand itself as a modern “fuel of the future,” it must strive to improve its environmental performance and deliver a cost-competitive product to customers.

The development of a renewable component to propane does just that for the propane industry.

“There is a kind of binary discussion for energy,” Alafia says. “You are either dirty or clean. Clean is defined as being renewable and if you are not renewable, you are kind of lumped into the other basket.”

To stay out of the “other basket” and join the future energy conversation, the propane industry is in the beginning stages of the renewable investigation.

“We can make the argument that conventional propane is good for the environment and that it is good economically for the users,” Perkins says. “But you need to have this renewable [component]. You need to be in the conversation about renewables because eventually we will be competing with wind and solar. You really have to be able to compete against those fuels.”

How it’s made

Any refinery that produces renewable diesel also produces a biogas and has the ability to refine further to produce renewable propane, Alafia explains.

A Renewable Energy Group (REG) biorefinery in Geismar, Louisiana, is one facility producing renewable propane on a commercial level.

Renewable propane is a co-product from a renewable hydrocarbon diesel (RHD) production process. RHD is a hydrocarbon product – hydrocarbons are chemical compounds composed only of hydrogen and carbon – like any of those that are the chief components of petroleum and natural gas. The difference is that RHD is made from biological oils and fats (triglycerides) through the process of hydrotreating. The combination of hydrogen and triglycerides produces renewable propane and paraffinic hydrocarbons – paraffins are waxy solids consisting of a mixture of saturated hydrocarbons – which are then isomerized to create a fungible diesel fuel that is separated from the lighter products, including renewable propane, by distillation.

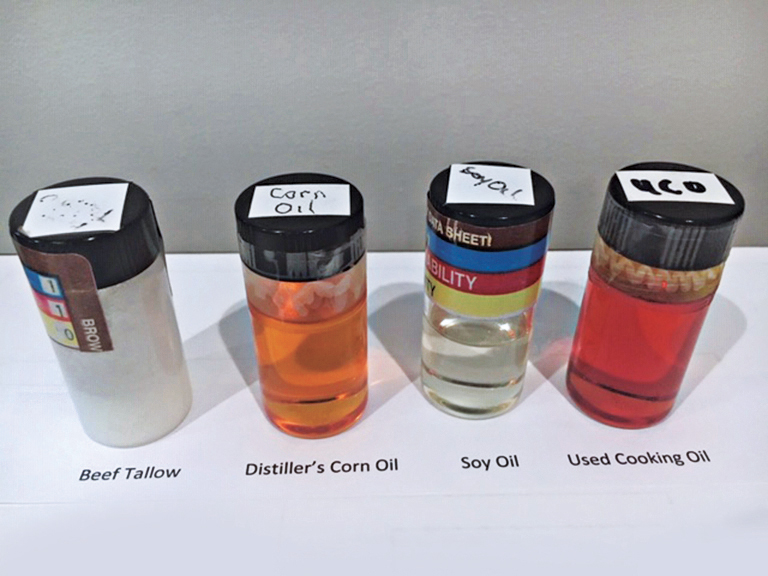

Beef tallow, distiller’s corn oil, soy oil and used cooking oil can be used as feedstocks in the renewable propane production process. Photo courtesy of World Energy

At press time, REG Geismar was the only refinery producing renewable propane on a commercial scale in the United States, although other refineries across the country have shown the ability to produce the renewable fuel. In California, Alafia explains, government agencies can provide credits and incentives combined with federal government credits to encourage facilities that already produce renewable diesel to take the extra step and produce renewable propane.

“We came into contact with REG and they assured us they are producing renewable propane today and they have customers for it,” Alafia says. “We met with them and shared the need that we see in California, so there was a lot of synergies there. Forward looking, we see renewable propane being available in California.”

Alafia forecasts 5 million gallons of renewable propane in 2019 and, assuming future renewable propane production capabilities are met, she hopes to see 18 million gallons by 2021.

Why turn to renewables?

Renewable energy, particularly renewable propane, emits a lower carbon intensity with similar performance metrics when compared to its traditionally-produced counterpart.

To decarbonize transportation, the California Air Resources Board is pushing for heavy-duty vehicles to be zero emissions wherever feasible or near zero emissions by using a renewable fuel. Photo: iStock.com/Si-Gal

To put it simply, carbon intensity is the amount of carbon or carbon content in a burning fuel. Fuels with lower carbon intensity will theoretically contribute less to greenhouse gases and global warming. Method of production is a major factor in a fuel’s carbon intensity number.

“What we realized was it is relatively easy to make renewable propane,” Perkins says. “The easier it is to make, the lower the carbon intensity, or let’s use real words: The less energy you need to put into it to make it into something useful. [For the propane industry] having renewable propane, even as a blended fuel with conventional propane, all of a sudden reduces the carbon content to the point where environmentalists and regulators sit up and notice.”

The carbon intensity of renewable propane depends on the feedstock being used in the production process. According to REG, used cooking oil produces 24.35 carbon intensity grams per megajoule (g/MJ); raw used cooking oil produces 18.99; corn oil 34.32; tallow 35.71; and soybean oil 56.57. Additionally, REG projects the carbon intensity of a glycerin-derived renewable propane to be about 40-45 g/MJ.

According to Alafia, having a renewable propane source with a carbon intensity around 40 g/MJ may be better versus electricity produced from coal. Perkins adds the lower intensity the better, but anything in the mid-30s is good.

Renewable propane in its gaseous form captured in a bag at room temperature and room pressure. Photo courtesy of World Energy

In January 2018, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), under sponsorship from PERC and WPGA, investigated pathways for production of renewable propane. The study found the carbon intensity of renewable propane from AltAir – a refinery in Paramount, California, with the capability of producing renewable propane – is estimated to be 31.5 g/MJ (base case using natural gas-derived hydrogen) and 24.7 g/MJ (using biomass-derived hydrogen), respectively to 59.3 percent and 68 percent carbon intensity reduction compared to conventional propane.

Despite environmental benefits, there are some economic hurdles in renewable propane production.

“The reason we haven’t used renewable fuels in the past is they tend to be more expensive and they tend to take more energy to make,” says Larry Osgood, president of Consulting Solutions LLC, who assisted NREL to answer questions about the propane market and how the technical work from the study fits into the industry.

Fueling the future

With a renewable component, the propane industry joins the conversation for the future of America’s energy portfolio.

The propane industry will compete in the coming years against zero-carbon renewable energy sources like wind and solar. Photo: iStock.com/serts

“This isn’t a technical conversation. For us, it is almost more of a philosophical conversation,” Perkins says. “We are not allowed into the conversation about how propane is a part of the environmental solution for 2030 or 2050 unless we demonstrate a renewable component. We are talking about one component of our fuel to be renewable, which for a policymaker lowers our carbon intensity and makes a meaningful advance toward propane use in the future.”

Investing in the future of propane today, Osgood says, is important for the industry. Alafia puts it more sternly: “We need to be a part of the energy evolution.”

“All fuels are stepping up their game in terms of making energy cleaner and we cannot afford to sit on the sidelines and produce the fuel the same way we have in the past,” she adds.

Adding a renewable component has two major advantages for the future, according to Alafia.

“One is to help rebrand our industry in the overall energy conversation as being a clean fuel that can deliver in terms of performance and power,” Alafia says. “There really aren’t a lot of fuels that benefit in terms of cost of transportability and with renewable propane. It just helps us with that conversation.”

The second is a real-world benefit of having a low-carbon fuel that reaps positive perceptions for the industry and the environment.

“I think renewable propane is nothing more than the vehicle by which many people will begin to listen more about how propane can be a part of the nation’s energy portfolio,” Perkins says. “We have a really strong story to tell, even if we didn’t have a renewable component. But without that renewable component, a lot fewer voices are listening.”

Targeting Transportation

Jon Leonard, senior vice president for Gladstein, Neandross & Associates (GNA), says renewable propane can succeed in the area of transportation.

GNA, a consultant organization involved in clean transportation energy with offices in Santa Monica and Irvine, California, works on clean heavy-duty transportation. Leonard explains there are four ways to get lower-emitting heavy-duty transportation, and one is through a cleaner fuel like renewable propane.

According to Leonard, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) is pushing for all heavy-duty vehicles to be “zero emissions wherever feasible,” and “near zero emissions (NZE) using renewable fuel” everywhere else. Heavy-duty propane engines that meet “near zero emissions” levels of NOx (0.02 grams per brake-horsepower hour), which is an advancement toward CARB’s plan for the transportation sector, are now available for medium-duty trucks, school buses and shuttle buses, Leonard explains. Renewable propane is now becoming available in small volumes for demonstration programs involving these NZE propane vehicles. However, it is not yet available in significant volumes to prompt a transition over from fossil-produced propane.

“In order to keep playing in California in the long-term transportation sector, you must get to renewable propane,” Leonard explains.

Patrick Couch, the vice president of technical services at GNA, suggests the most economic value for renewable propane today is in transportation. The use of renewable propane in transportation is not the only long-term use, but it is also something short term into which the industry can tap.

“The infrastructure is very cheap compared to electricity or natural gas,” Couch explains. “And it’s relatively easy to store the fuel on board the vehicle to get the range you need. Those advantages of traditional propane carry over to renewable propane while providing greenhouse gas emissions reductions comparable to electricity or renewable natural gas.”

Larry Osgood of Consulting Solutions argues for more propane use both in transportation and other, more traditional applications.

“We get much better emissions results across the board using propane,” Osgood says. “I believe we should be using more propane and not less.”