Connecticut launches gas cylinder recycling program

A new residential gas cylinder stewardship program in Connecticut is reshaping how cylinders are collected, reused and recycled.

The program is the result of an extended producer responsibility (EPR) initiative that industry stakeholders and Connecticut lawmakers collaborated on in 2021 and 2022. Worthington Enterprises (known then as Worthington Industries) helped to steer the legislation to where it better represented residential gas cylinder producers as well as the propane industry, the company explained at the time.

Connecticut enacted the first statewide EPR law for certain gas cylinders in 2022, and the program officially launched in October 2025.

“This program proves that industry can lead on practical, sustainable solutions that keep consumers safe, reduce waste and support environmental goals,” says Gary Haines, director of regulatory affairs at the Propane Gas Association of New England (PGANE), which is managing part of the program. “Connecticut is setting a model that other states can follow.”

▶ PRO effort

Three producer responsibility organizations (PROs) are collaborating to manage the residential gas cylinder recycling program within the state, and a regional propane association is playing a key role.

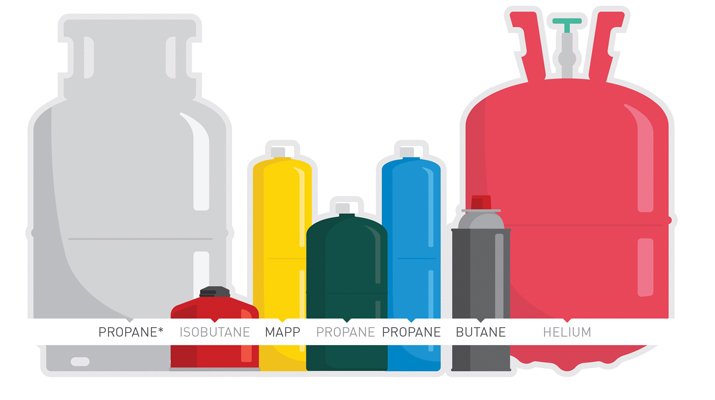

PGANE is the program responsible for the 20-pound barbecue grill cylinders, while the Cylinder Collective, a collaboration of cylinder producers, handles the smaller containers often used for camping, cooking, do-it-yourself projects and other household tasks. These types of cylinders contain gases such as propane, butane, propylene and helium. SodaStream is working as the PRO for carbon dioxide cylinders using a mail-back system.

Qualified companies within the PROs will pick up, transport and recycle cylinders that are collected at various locations across the state. The PROs can collaborate with one another to help direct cylinders to the correct program.

“We’ll see a lot less concerns from the municipalities on all types of cylinders in the state of Connecticut,” says David Keeling, executive director of the Cylinder Collective.

The Cylinder Collective is securing additional collection sites. It’s focused initially on municipal transfer stations “because they tend to be the first place that residents look to bring material,” Keeling says.

“We’ve already collected about 4,000 cylinders. A lot of those were cylinder backlogs that facilities already had from those operations,” he adds in mid-October. “So, we’re well on our way.”

As the program gets underway, and word spreads with the help of consumer educational materials, press releases and social media, the Cylinder Collective will look to collect cylinders from state parks and campgrounds, recycling facilities and household hazardous waste collection events as well, Keeling says. The collective numbered 36 sites in mid-October, and Keeling believes it will reach 50 by year’s end.

“There are 160 municipal transfer stations throughout the state of Connecticut,” he says, “so we have room to grow.”

▶ Barbecue grill cylinders

From the beginning, PGANE felt confident that the propane industry’s vast cylinder exchange network was already working to properly collect and recycle the barbecue grill cylinders.

But when the 20-pound cylinders became part of the Connecticut law, the association gathered cylinder manufacturers, propane marketers, exchange service providers and local governments and developed its refillable 20-pound cylinder stewardship program. It’s designed to remove the burden from municipalities and integrate unwanted cylinders directly into the existing exchange system.

AmeriGas, Blue Rhino, Flame King, Hocon Gas, Manchester Tank, Paraco Gas, U-Haul and Worthington Enterprises are part of the propane industry coalition backing the program.

“Our system really is [about] outreach, letting people know the best way to get rid of these size tanks is to take them to an existing exchange cage at your convenience store, your hardware store. And, if you have a tank you don’t want to exchange, to drop it off” at those exchange locations, says Leslie Anderson, president and CEO of PGANE.

Haines adds, “The whole point to this has always been to put these steel tanks back in the field and to recycle and reuse them rather than just destroy them.”

Still, according to PGANE, municipalities and transfer stations across Connecticut have struggled for years with the costly and sometimes dangerous task of managing unwanted propane cylinders. These tanks, commonly used for grilling, are left at transfer stations or illegally dumped, posing safety and environmental hazards.

“We want to keep these propane tanks out of the recycle centers and the transfer centers where they can get cut up or punctured,” Anderson says. “So, we’ve got a lot of safety information that’s part of this too that goes out to people on how to recycle. Everything is about recycling your propane tank.”

In addition, the program allows free pickups for municipalities. Transfer stations, state parks and other eligible sites can schedule free retrieval of 20 or more cylinders. Collected cylinders within the program are inspected, refurbished when possible or responsibly recycled – with residual gas captured safely, PGANE says.

To get consumers to integrate unwanted cylinders back into the existing exchange system, which is composed of more than 600 locations in Connecticut, PGANE has orchestrated a comprehensive consumer education campaign using a $60,000 grant from the New England Propane Foundation.

PGANE and the Propane Education & Research Council have developed signage, brochures, a website and digital outreach materials to raise awareness of proper disposal methods. PGANE is managing the entire effort in-house with Haines as the point person.

The goal for PGANE in the first year, Anderson says, is to send letters to all the towns and municipalities in Connecticut to educate them about the program.

“We’ve got all this information [on the website at pgane.org], and you can use it for any state in New England,” Anderson says. “So, it’s all safety and training related, right? It is still good for consumers to know throughout New England what to do with a propane tank they want to recycle. So even though the plan is only required in Connecticut, it benefits everybody in New England.”

▶ Association leadership

Like the Cylinder Collective, the national Pressurized Cylinder Industry Association (PCIA) was born out of the Connecticut program. Keeling is the executive director of the PCIA as well.

The PCIA is a nonprofit trade association composed of pressurized cylinder producers with a shared emphasis on product stewardship.

Keeling, who spent nearly 30 years in the steel recycling industry, says, “We advocate and respond to legislation. We also provide a resource for state agencies or state legislators who are looking into some type of law, an EPR law or something to do with cylinder recycling.”

So, what’s happening in Connecticut has formed a foundation and created a blueprint for others to follow. As other states explore EPR strategies for difficult-to-manage materials, PGANE says, Connecticut’s cylinder program is emerging as a national model for producer-led environmental stewardship.

“Absolutely,” responds Anderson, when asked if the Connecticut program could serve as a model for the rest of the country.