Propane’s role in oil and gas fields

Houston-based EOG Resources is one of the largest oil and gas companies in the U.S. Photo by Harris Baker

If you’re located in the vicinity of shale plays, landing an account at a hydraulic fracturing (fracking) site can be a lucrative strike drawing high-gallon propane purchases.

Although waterless fracking processes using propane to conduct oil and gas extraction procedures from surrounding rock have been used over the years, propane applications are far more common when put to work on an assortment of aboveground functions.

Electric motors abound on these sites, along with an associated demand for power generation. Propane-powered drilling rigs, flaring assistance burners, oil and water heaters, pumps, compressors, forklifts, propane-fueled vehicles, and heaters and cook stoves for worker housing units are all on the job at fracking sites.

While remaining highly dependent on your regional marketing area, of course, the overall oil field sector is booming as the nation shifts from being a net oil and gas importer to a net exporter.

“The United States energy system continues to undergo an incredible transformation,” says Linda Capuano, chief administrator of the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). “This creates a very different set of expectations than we imagined even five or 10 years ago.”

Driven largely by improved fracking and horizontal drilling techniques, in conjunction with favorable economic conditions, domestic petroleum pumping has attained monthly levels not seen since the 1970s – roughly 9.7 million barrels per day (bpd) – with the EIA projecting that annual production will reach a record high this year. In January, American shale developments alone were on pace to produce more than 6.4 million bpd.

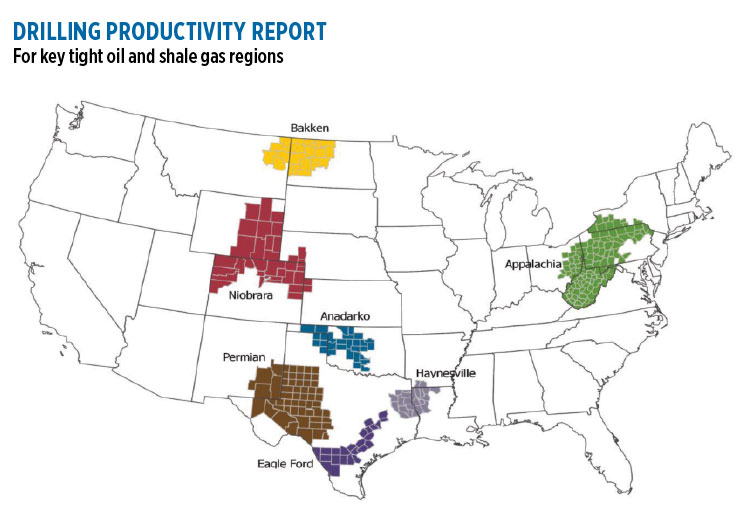

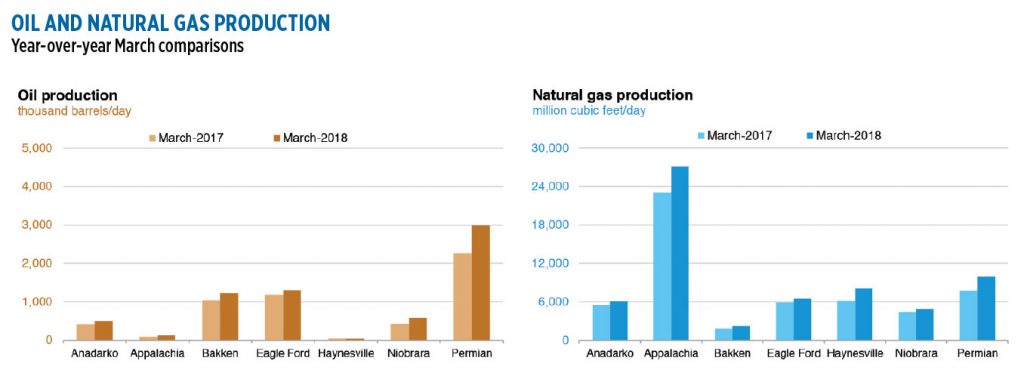

U.S. crude oil production is forecast to increase from an average of 8.9 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2016 to an average of 9.3 million bpd in 2018, primarily as a result of gains in the major U.S. tight oil-producing states, the U.S. Energy Information Administration says.

Hotspots include the Permian Basin in West Texas and southeastern New Mexico – which is already up nearly 700,000 bpd over 2017 figures – as well as opportunities in California, Alaska and other select oil- and gas-bearing regions across the country.

If there’s a fly in the ointment impacting the industry’s oil field presence, it’s the dominance of diesel as the fuel of choice among fracking practitioners not yet attuned to propane’s benefits.

The Permian in Texas and Appalachia, which is mainly composed of the Marcellus and Utica shale plays, are key oil and gas producing regions, respectively, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Click to enlarge.

“We’ve had a little bit of a difficult time convincing oil people to switch over to propane – they’re stuck on diesel, and they’re sticking as hard as they can to diesel,” says Dave Luciani, president of Texas-based power generation unit provider DynaGen Oilfield Energy, a division of Houston Natural Energy.

This attitude persists despite DynaGen’s pitching of propane’s attributes, which include:

- Capital savings on fuel consumption between 20 percent and 30 percent;

- Greenhouse gas emissions reduced by 35 percent;

- About a 9 percent reduction in sound levels compared to diesel generators;

- 10 percent savings on the initial purchase of units compared to similarly sized diesel gensets;

- Reduced amount of fuel deliveries, leading to lower costs and higher environmental benefits;

Luciani is optimistic, however, that within the next five to 15 years, there will be a significant shift to propane.

The love affair with diesel is bound to eventually part ways in favor of propane, agrees Mike Lisk, co-owner of Remote Well Solutions in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and inventor of the Frac Well Watchman.

Lisk believes much of the affinity for diesel has more to do with established relationships between drillers and diesel vendors rather than a comparison between the fuels. The propane industry as a whole can build a stronger foothold by conducting increased outreach with oil and gas executives, he adds.

“We still see opportunity with this in the oil fields,” says Lisk. “We came up with a pretty unique development with this pumping plant. It’s a generator with our controls on it. When you frack a well, you use a lot of water.”

Unlike diesel units, a propane engine can automatically start and stop as needed to keep pace with a water well’s recharge rate, even when climate extremes are present.

“Propane’s a wonderful fuel. The cold-weather starting with propane is great,” Lisk says.

Also unlike diesel, a tank of propane can be stored indefinitely at a remote, rugged location.

Facilitating the transition

Caterpillar unveiled an engine for gas compression systems that facilitates piping a well’s output from the site. Propane or well gas can power the unit. Photo courtesy of Caterpillar

In certain situations, a single well can be served by up to four electrical generators.

They’re outrunning the grid with power needs, says Harris Baker, formerly of Texas-based Pinnacle Propane and now with HBH Gas Systems. “You’re in the middle of nowhere and it may not be practical to run a power line out there.”

Until a well’s production is up and running, alternative energy sources are required.

“The goal is to power those generators off the natural gas coming out of the hole,” Baker explains. “We facilitate the transition. We power the generator for the initial 30 days or so. They’re working and tweaking to get it stabilized, and then they’ll leave us behind as a backup. Switching propane over to natural gas is easy – they can do it in one fell swoop. If something happens to the gas coming out of the well, it switches over to propane automatically.”

Caterpillar’s oil and gas division unveiled a stoichiometric engine for gas compression systems that facilitates piping a well’s output from the site. The new G3516 TA model uses the Cat diesel platform as the stoichiometric aspect, and dynamic gas blending capability permits propane and various grades of well gas to power the unit, the company reports.

In addition to fueling equipment, propane is bringing comfort to field offices and workforce housing lodges.

One Kansas propane retailer says the oil and gas segment can be “up and down.” Photo by Harris Baker

“Their most valuable assets are the employees. These are a good environment for their tenure out there. Safety’s a really big deal,” Baker says, referring to the importance placed on desirable housing accommodations offering attractive amenities. “They’re huge – they may have 500 individual bedrooms in them. These are out in the middle of nowhere, and they run on propane.”

At one particular lodge, Pinnacle Propane even filled propane-powered vans that transported workers to and from the rigs.

“We had the whole propane equation out there,” says Baker.

A laundry list of LP gas

Drilling companies strive to keep all of their DUCs – “drilled but uncompleted” wells – in a row.

“It’s cheaper to drill than it is to produce,” Baker says.

A hole is sunk and a giant stopper called a “Christmas tree” is affixed as the crews move to the next drilling site.

“When it’s time to start producing, they bring a propane generator in,” he says. “They use propane because of the savings, and these guys are working really hard to be ‘green.’”

Although some form of gas may indeed be emanating from the well, during the initial stages it can be unsuitable as a fuel. This is where flaring enters the process – to eliminate waste APG, also known as “associated petroleum gas.”

Propane fulfills power generation needs in oil and gas fields. Taylor Power Systems, with one of its units shown here, runs generators on diesel, natural gas and propane. Photo courtesy of Taylor Power Systems

When the adverse vapor is so faulty that it defies burning, propane provides an assist to get the flames going.

“We do a lot of flare gas,” says Baker, a longtime industry activist who serves on the market outreach and training working group of the Propane Education & Research Council and is secretary at the Propane Council of Texas.

At Ratcliff Propane Gas in Madison, Kansas, Travis Ratcliff markets propane that’s mixed with natural gas to improve performance as it wafts up from the depths.

“You have to get the moisture out of that gas coming out of the well. It’s a separation pod. The propane is added right before carburetion; it’s just the two chemicals coming in contact with each other,” he says.

“It’s up and down,” says Ratcliff of his local oil and gas segment. “When the oil field is going well, the business is good. It’s something to do in the summer. Most of the wells around here have gone to soup – it’s pretty well dead – but we still have places where electricity isn’t out here yet.”

The company has a reliable fracking customer actively fueling hot oil burners.

Back in the heady days when the area’s robust black gold market was hitting pay dirt, he recalls that “it was a full-time job in the summer and even busier in the winter. I’d ride in the truck with my uncle, Jack Williams, and my grandfather, Jack Ratcliff, and we were super busy all the time.”

Down in East Texas, “It’s not as big as it was four or five years ago, but it’s picking up,” says Josh McAdams, vice president of the McAdams Propane Co.

Currently 20 percent of the business involves oil field applications. Services include:

- Bulk site deliveries

- Skid tank refueling

- Supplying propane-fueled generators at well sites and for contractors

- Supplying 250-gallon-or-larger propane tanks, setup and delivery

- Portable heaters for contractors

- Fueling for water heaters

“Hot water is easier to pump than cold water; it’s less resistance,” says Keith Fronk, president of Fronk Oil Co., established in 1947 in Booker, Texas.

Honeywell UOP will provide a 200-million-cu.-ft.-per-day gas processing plant to Brazos Midstream in the Permian Basin. Photo courtesy of Honeywell

Fronk supplies propane to Western Hot Oil Services of Perryton, Texas, which consumes some 75,000 to 100,000 gallons of propane per week, according to Western’s operations manager, Richie Gastineau.

Western Hot Oil Services employs 65 people manning a fleet of 67 specialized vehicles.

“Most of the bigger heating units are 42 million Btu, and they burn 250 gallons of propane per hour,” says Gastineau. “We also have a fleet of hot oil trucks, and they burn 100 gallons an hour.”

Along with on-site storage tanks, LP gas deliveries from Fronk are a daily thing, he notes, complementing the 24/7 on-the-spot service he receives.

“We’ve used them since we began in the business 20 years ago, so we’ve been doing business with them for a long time.”

Oil being drawn from a well can take on an overly thick, waxy viscosity that stymies pumping processes.

“They heat oil and pump it down the hole to heat the wax,” says Jordan Larson, general manager at Hellian Oil field Services in western Canada.

“I burn the propane,” he adds, explaining that the company purchases vast amounts from Midwest Propane in Alberta, Canada, a division of Tidewater Propane, for heating both oil and water.

“It’s quite the volume we’re dealing with,” Larson says.

One such reservoir is the size of a small town, and the whole lake must be heated because it will freeze if left unattended during cold Canadian winters, he adds.

Midwest’s oil field business “has definitely picked up since the price of oil went up,” says Wyatt Lund, general manager.

Lund estimates that a larger oil field services provider that he supplies buys nearly 8 million gallons annually.