Can the US stop Russian energy imports and supply Europe?

Trader’s Corner, a weekly partnership with Cost Management Solutions, analyzes propane supply and pricing trends. This week, Mark Rachal, director of research and publications, examines the U.S. energy position in light of the events in Ukraine.

The tragic events in Ukraine have been heartbreaking. Almost everyone who has seen the images of war and the pleas of the Ukrainians for help want to respond in some way. One way we thought we could respond is to try to bring some clarity to the U.S. energy position. We hear a lot of political positioning and rhetoric about what should be done and placing the blame for why our nation’s response seems so impotent, considering the enormity of what is happening in Ukraine.

Two key points related to energy have garnered the attention of most politicians. First is the fact that the U.S. imports 670,000 barrels per day (bpd) of crude and crude products from Russia. Second is the idea that if the U.S. energy sector were unshackled, it could replace all of the energy that Europe currently gets from Russia. In this Trader’s Corner, we will provide some information and background on the first issue.

Crude imports from Russia

It is true that U.S. companies sourced 672,000 bpd of crude and crude products from Russia in 2021. Some major U.S. oil companies have partnerships with Russian oil companies. Unrefined crude was 199,000 bpd of the total, with refined fuels at 473,000 bpd. The volume increased in 2021 from a total of 540,000 bpd in 2020. The breakdown that year was 465,000 bpd of refined fuels and 76,000 bpd of crude. To be clear, the U.S. was getting crude and refined products from Russia during both Republican and Democratic administrations.

Some rhetoric insinuates the U.S. government is directly buying this energy from Russia. That is not true. The product moving from Russia to the U.S. is a result of free-market commercial enterprise. The crude is being used by U.S. refiners such as ExxonMobil, Chevron and Valero as feedstock for Gulf Coast refineries. The refined fuel is augmenting supplies from perhaps these companies and others. The U.S. government could sanction these movements, but we believe it is likely commercial players will voluntarily curb these movements.

However, the U.S. government and thus the American people are culpable in this commercial business being necessary. The idea of a refinery in one’s locale has been so ominous that the regulations, restrictions and costs have made it almost impossible to build a new refinery. The last new refinery was built in the U.S. in 1976. Since then, increased capacity has occurred only by expanding existing facilities.

The public acceptance for drilling oil and gas wells or building pipelines or petrochemical facilities is nearly equal to that of refineries. Thus, only a relatively small area of the nation is willing to tolerate anything related to the hydrocarbon industry. As a consequence, major U.S. oil companies focused investment in more politically favorable environments. One of those is Russia. ExxonMobil and Chevron have production and pipeline ventures in Russia. Major oil companies domiciled in other nations like France, the Netherlands and Great Britain have done the same.

While building new refinery capacity became nearly impossible, demand for refined products continued to increase. Major oil companies leveraged their relationships in Russia and started bringing refined fuels from there to their home nations. This is not a new phenomenon. Crude and refined fuels started flowing from Russia to the U.S. in May 1995.

US crude trade balance

Amazingly, despite the challenging environment, the U.S. is still a net exporter of crude products. In January, the U.S. imported 1,841,000 bpd of crude products and exported 4,192,000 bpd for a net export rate of 2,351,000 bpd.

Our refined fuel exports go to Canada, Mexico, South America, the Caribbean, Japan and South Korea mostly. These are longstanding business relationships and, in most cases, good allies. It would not be in our best interest to end these exports to stop importing from Russia. Still, the imports of refined fuels from Russia seem to be replaceable.

In January, the U.S. refined 15,456,000 bpd of crude, which was just 85.2 percent of refinery capacity. Capacity utilization has been as high as 98.1 percent, but that would be hard to sustain. However, to replace the refined fuels received from Russia, it would take only a utilization rate of 87.5 percent of the nation’s 18,132,000 bpd of refinery capacity. That is a refinery throughput rate of 15,871,000 bpd. Our highest throughput rate ever has been 17,981,000 bpd in August 2018. Unfortunately, our refinery capacity has dropped from 18,599,000 bpd to 18,132,000 bpd. Some unprofitable refineries that were damaged by hurricanes have not been restarted.

Replacing the crude imports may be more complicated. The U.S. is a net importer of crude. In January, the U.S. imported 6,530,000 bpd of crude and exported 2,536,000 bpd, making it a net importer of 3,994,000 bpd. The U.S. is short heavy crude, which it’s getting from Russia. When the U.S. refinery complex was built, it was designed to process a lot of heavy crude. U.S. crude production was heavier then, and we got our heavy crude imports from Venezuela, Canada and the Middle East. It would take a lot of time and billions of dollars to change the refineries to run without the heavier crudes, so the alternative has been to blend heavy crudes from foreign sources with our production.

Almost all of the new crude production in the U.S. is coming from shale formations now, which is a much lighter crude. In fact, 89.7 percent of our current production is considered light crude, with an API gravity of greater than 30. That is one of the reasons we are both an importer and an exporter of crude. We are exchanging light crude for heavy crude. Over 60 percent of our crude imports are heavy. Getting heavy crude became more complicated in 2019, and once again the U.S. government was complicit.

Geopolitical factors

The U.S. used to get a major portion of its heavy crude from Venezuela, but imports from there were banned in 2019, and China now essentially controls those barrels. Venezuela’s production had been going down for years due to the corruption in that country. Still, in 2018 the U.S. averaged 586,000 bpd in heavy crude imports from Venezuela. In 2019, the U.S. put an embargo on Venezuelan crude primarily to try to force a regime change. China thwarted those ambitions, and now the U.S. gets no Venezuelan crude with most of it going to China.

Western Canadian crude is heavy, with an API gravity of 20. A tremendous benefit of the Keystone Pipeline was to get that heavy crude safely and efficiently to Cushing, Oklahoma, and then to the U.S. Gulf Coast, where most of the U.S. refining capacity exists. The Keystone Pipeline is complete. Phase 1 goes from Hardisty, Alberta, Canada, to the junction at Steele City, Nebraska, and then to refineries around the Chicago area. Phase 1 went online in June 2010.

Phase 2 from Steele City, Nebraska, to the U.S. trading hub of Cushing, Oklahoma, went online in February 2011. Phase 3a from Cushing, Oklahoma, to Nederland, Texas, feeding refineries at Port Arthur, Texas, went online in January 2014. Phase 3b, online in 2017, was a lateral pipeline taking crude to refineries in the Houston area.

The controversial line is the Keystone XL, which would have run from the original Hardisty, Alberta, Canada, starting point taking a more direct route to Steele City, Nebraska, via Montana, South Dakota and Nebraska. The route would have allowed light crude production in the U.S. to be added to the line. This was important to give U.S. production access to markets, plus diluting the heavier crude, making it more efficient to pump and increasing capacity. The Keystone XL was abandoned in June 2021, only 8 percent complete. Because of this, some of the crude produced in the Bakken shale formation in Montana and North Dakota is moved by rail. The Keystone XL pipeline would have had a capacity of 830,000 bpd. The line would have been filled by production from Canada and the Bakken. Most of that volume will have to be moved by rail. There have been several high-profile derailings of crude trains in Canada and the U.S. Moving crude by pipeline is considered safer, cheaper and more environmentally friendly. However, the Keystone XL pipeline route went through sensitive Native American lands. President Joe Biden signed an executive order revoking the Keystone XL pipeline permit on his first day in office.

The existing northern portion of the Keystone moves about 500,000 bpd of crude from Canada to the U.S. The year this pipeline went into service, Canada exported 2,535,419 bpd of crude to the U.S. In 2020, Canada shipped 4,136,016 bpd. However, that is down 295,000 bpd from the year the U.S. lost the Venezuelan heavy crude supply. Combined, from 2019-20, the U.S. was down 881,877 bpd of critical heavy crude supply from what had traditionally been its two top suppliers. This put pressure on refiners to source heavier crude from other countries, including Russia.

The easiest way to make sure the U.S. has the heavy crude it needs would be to restore the relationship with Venezuela. That would take a major warming of relationships with both Venezuela and mostly China, since it pretty much owns Venezuela from an energy standpoint. This is highly unlikely. The more practical option is to make the movement of heavy crude from Canada to the U.S. as easy, safe and cost-effective as possible.

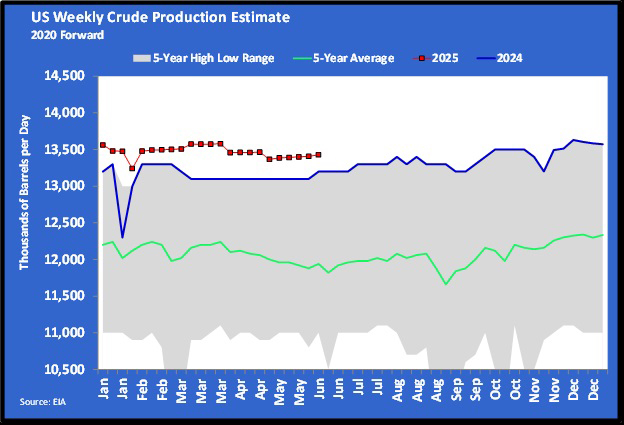

There is outrage over Ukraine, and there is always the instinct to politicize it and place blame. The fact is both parties have contributed to the U.S. buying Russian crude and crude products. Even though these movements have not been sanctioned by the U.S. government, there is a good chance they will be greatly reduced by the commercial players involved. It is true that recent actions by the government have made it more difficult on the energy industry. Perhaps those policies should be reconsidered in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, to this point, the reduction of U.S. crude production that is now 1.6 million bpd below its 13.2-million-bpd peak has been due to commercial and economic reasons, not government mandate or action.

It is a time to be smart, decisive and forward-thinking concerning our energy policies, which is exactly what our advisories are doing with energy and other matters. Energy is absolutely a matter of national security and should not be politicized. It is in our best interest to continue to convert to environmentally friendly sources of energy that replace hydrocarbons. However, we must be realistic about where that process stands now and how long it is going to take to replace hydrocarbons as our primary energy source. In the meantime, putting our energy needs and security in the hands of other nations does not solve the environmental issues and indeed may make them worse. It can also have dire geopolitical consequences, as demonstrated by what is happening in Ukraine. We must have strong bipartisan leadership on this matter immediately, and that is not optional.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how client services can enhance your business at 888-441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.