Propane makes push to replace diesel in ports

A continued push to displace diesel in a variety of applications plus $450 million in funding opportunities from new federal infrastructure legislation is helping to position propane as a fuel of choice in ports.

Propane’s already accustomed to powering material handling equipment. It’s common to see propane-fueled forklifts tackling the heavy loads while moving efficiently inside and outside warehouses across the country.

The work being done in ports plays off the 600,000 propane forklifts in operation today, according to the Propane Education & Research Council (PERC), and it’s extending the reach on the type of equipment that works well with LPG.

“We’ve been bird-dogging ports for two years now,” says Tucker Perkins, president and CEO of PERC, noting how the council works daily in this segment and calling it a “task at hand.”

Perkins doesn’t hide his passion for propane use in ports, a topic he addresses often during presentations to propane industry audiences.

“This goes to the heart of the whole environmental debate, which is ports are such intensive users of energy,” he says. “Everything there is intensely diesel, and everything there should be intensely propane.”

“Plain and simple,” adds Joe Calhoun, director of business development at PERC, “what makes the market attractive is the diesel-centric nature of it today. From a diesel-replacement perspective, we stand a lot to gain in the ports.”

Port locations – both along the coasts and inland – also play a key part in the need for a lower-carbon fuel option like propane.

“Ports are always around a lot of industry and a lot of people, so there’s a real need for clean air,” Perkins says. “They tend to be 24/7 operations, so there’s a lot of benefit when you clean up their equipment.”

Tryaging/iStock / Getty Images Plus/Getty Images

Port equipment

There isn’t a port today that doesn’t use propane in some part of its operation, Calhoun says.

“Propane is a versatile, portable fuel,” he says. “There’s a lot of equipment that needs a versatile, high-density fuel like propane.”

Calhoun recalls conversations prior to joining PERC in 2020 about propane-fueled port tractors and engines. Now he’s seeing movement in the market.

“Today we’ve got at least three manufacturers that are on board, looking at producing some quantity of port tractors with a propane engine,” he says, noting the work of South Carolina-based TICO, a manufacturer of terminal tractors and trailers. “That’s exciting.”

Port tractors come up often in conversations and presentations about the type of equipment propane can fuel in ports. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) addresses their role and offers best clean air practices for port operations to reduce diesel pollution and associated health impacts. Here’s a closer look at port equipment.

Port tractors: Also called yard trucks, yard hostlers or terminal tractors, they are typically a low-power semi-tractor with a single-person cab and short wheelbase. They account for most of the cargo handling equipment emissions at container terminals, according to the EPA.

Propane-powered port tractors produce less emissions and cost up to $200,000 less than electric models, PERC notes, meaning ports can afford to replace more of their fleet and achieve carbon-reduction goals faster.

Specifically, efficient fuel delivery (using forklift cylinders), minimal cost and impact for on-site refueling infrastructure, an improved emissions profile and a reduced cost of ownership all make propane a logical fit for these tractors, Calhoun says. Propane refueling infrastructure is already affordable, scalable and readily available.

Even smaller terminals and port tractor fleets are “golden opportunities for our fuel” because the units are always moving, he adds.

Drayage trucks: These trucks transport containers and bulk freight between the port and intermodal rail facilities, distribution centers and other near-port locations. The EPA cites alternative fuel drayage trucks as one option for ports to improve air quality, especially as new truck models with low-NOx tailpipe emissions (e.g., LPG and natural gas) and zero tailpipe emissions (e.g., electric and fuel cell) come into the market.

“They are historically older model diesel trucks, maybe poorly maintained because they sit so long waiting to get loaded and then they run their container,” Perkins says. “It’s where the opportunity is to clean the air because they’re high idle; they don’t run a lot of miles, but they’re on a long part of the day.”

Container handlers: Mobile equipment that lifts, moves and stacks containers in a port terminal.

Cranes: Of the various types of cranes used by ports, rubber tire gantry cranes are typically powered by diesel engines and account for the bulk of crane emissions at most container terminals, the EPA says.

“They’re picking up a container and moving it down an entire row of stack containers to get it to the top of the first row,” Calhoun says of the gantry cranes.

Ports are also working to decarbonize by bringing rail closer to their operations “because a train leaving a port with a lot of containers is decarbonizing versus a convoy of trucks idling on diesel fuel,” he says. “So that’s created a need for things like port-to-rail equipment.”

Additionally, Calhoun contemplates how propane can help lower emissions in the areas of tugs and ferries, shore power (or cold ironing) and barge-mounted scrubbers.

PERC also promotes a wide range of portside applications suited for propane, including shuttles/transit, light- and medium-duty vehicles and commercial generators. Propane-fueled generators also provide recharging for electric vehicles.

“A port uses an enormous amount of electricity,” Perkins says. “We have a fair amount of conversation with ports about using stationary power from propane as well.”

Perkins and Calhoun say propane makes the most sense from a cost and infrastructure standpoint, but challenges remain as some ports, agencies and states are still focused on other energy sources.

“Propane would be considered a cleaner fuel but not a zero-emissions fuel, and that’s where the state mandates are taking us,” says Tom O’Brien, executive director of the Center for International Trade and Transportation, California State University, Long Beach. “In California, it would be battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell for trucking and handling equipment.”

While propane industry leaders prefer to evaluate emissions performance using a full-fuel-cycle comparison and gaining an edge against grid electricity, they also continue to develop a renewable component to help them meet strict mandates.

Getting to know the ports

The American Association of Port Authorities represents more than 130 public port authorities in the U.S., Canada, the Caribbean and Latin America.

Perkins says PERC focuses its efforts on a handful of areas in the U.S., including the Port of Seattle and the Port of Tacoma (Washington); the Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach (California); the Port of Houston and the Port of Galveston (Texas); the Port of Charleston (South Carolina) and the Port of Savannah (Georgia); and the Port of Miami (Florida).

The Port of Los Angeles, referred to as the busiest seaport in the Western Hemisphere, started strong in 2022 as it reported its busiest February in its 115-year history, representing back-to-back record months to begin the year. Its West Basin Container Terminal operates propane port tractors, Calhoun says.

The Port of Long Beach has long been heavily dependent on propane, Perkins says, and PERC also has an extensive relationship with ports in Virginia.

“All are familiar with propane forklifts,” he says of port operators. “Now they’re getting familiar with port tractors, some of the reach stackers and other equipment.”

“Anytime we as an industry can get them to switch over to any kind of [propane] equipment, it’s always a plus,” adds Justin Unger, the general manager for Ferrellgas’ location in Garden City, Georgia, a suburb of Savannah. His location services 33-pound forklift cylinders for the Port of Savannah.

Perkins alludes to an impending “big announcement” by a prominent company that’s making a “huge investment” in propane for use in the ports.

Federal infrastructure legislation

The U.S. Department of Transportation is opening the $450 million in funding for initiatives that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and minimize impacts to the climate and surrounding communities from port operations. Areas targeted for projects include coastal seaports, inland waterways and Great Lakes ports.

The funding is part of the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act signed into law late last year to improve America’s infrastructure. The act provides over $9 billion in funding for refueling infrastructure and clean vehicles and equipment. Propane is recognized in the act as an emerging alternative energy source.

“The real driver now is these ports are seeing a need to clean up, and the infrastructure bill gives them a fair amount of money,” Perkins says.

Ports can apply for the funding at grants.gov by 11:59 p.m. Eastern time on May 16.

Cargo handling equipment

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says port tractors, cranes and container handlers produce the bulk of cargo handling equipment emissions at ports with significant container operations. Other cargo handling equipment at ports includes:

- Aerial lifts

- Compressors

- Excavators

- Forklifts

- Generators/power packs

- Light towers

- Manlifts

- Off-highway trucks

- Rail pushers

- Reach stackers

- Rollers

- Side handlers

- Skid steer loaders

- Sweepers

- Welders

Source: EPA

Decarbonizing with propane

According to PERC, propane engines and equipment are often the cleanest solutions in many areas. In fact, an environmental comparative analysis conducted by the council takes a hard look at the lifecycle emissions profiles of propane and electric-powered forklifts, including carbon dioxide and nitrogen oxide emissions. Findings show, for several states, conventional propane engines are superior to electric forklifts, especially when considering marginal emissions. “This is exactly why we are emphasizing this market,” says Joe Calhoun, business development director at PERC, about the ports. “The fastest way to decarbonize that space is with propane.”

Propane-fueled engines/systems that can help power port equipment

- Ford 7.3-liter

- Power Solutions International 8.8-liter

- Roush CleanTech 6.8- and 7.3-liter

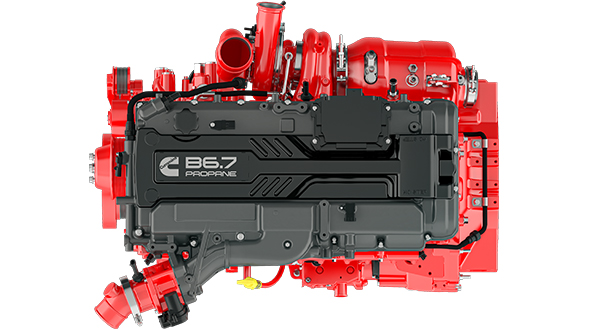

- Cummins 6.7-liter (in development)

Cummins plans to add gasoline, propane and hydrogen to its B6.7 portfolio. (Photo courtesy of Cummins Inc.)

Gallon sales estimates

While PERC doesn’t specify gallon use or volume potential from propane-fueled port equipment, it does track gallon sales in the larger internal combustion sector, composed of material handling, autogas and non-road subcategories. (Material handling gallon sales data only includes odorized propane use by forklifts at commercial and industrial sites as well as airport and port equipment.) In 2020, the latest year for available data, this entire sector accounted for 589 million gallons in propane sales, averaging about 2,500 gallons per account and representing 6 percent of total sales.

Port resources

- American Association of Port Authorities

aapa-ports.org - Environmental Protection Agency

epa.gov/vessels-marinas-and-ports - Maritime Administration

maritime.dot.gov - Propane Education & Research Council

propane.com/for-my-business/material-handling-for-ports