Retailers can use swaps to lock down future prices

Propane retailers know they are going to sell propane in the future. They have the customer base, and they roughly know how much propane each of those customers will wish to purchase from them over the coming months. What they don’t know is how much they will have to pay their supplier for the propane during the months their customers will demand it.

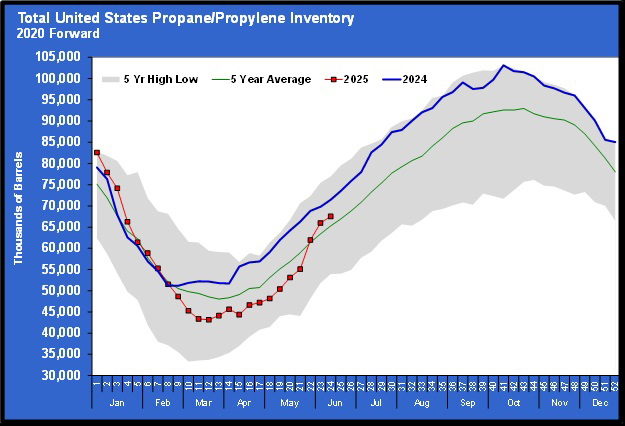

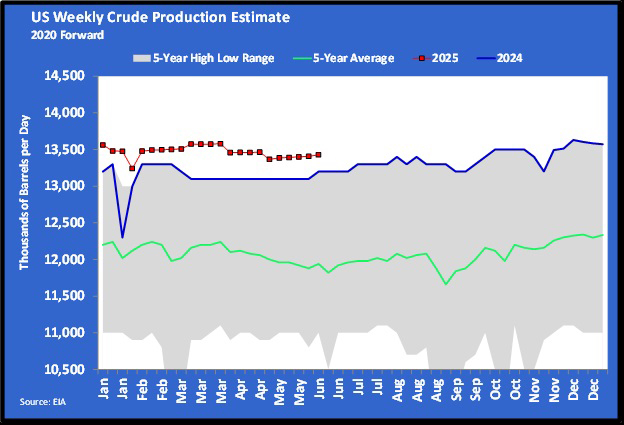

Propane is at modern-day lows, with both Mont Belvieu LST and Conway propane slipping below 20 cents per gallon this past week. Prices have recovered some, but the situation surrounding the price of propane remains volatile. Many retailers look at the current price and wonder just how much downside risk there is in owning 20-cent propane. Well, there is at least 20 cents of risk, and we can’t say propane can’t go below zero as proven by ethane a few years ago. By this point, no one should ever say “never” in this business.

Still, if a retailer had the money to buy and the storage to hold all of the propane they will sell over the next one, two or three years at today’s price, it is hard to imagine that wouldn’t work out rather well. But, does anyone have that much money or storage sitting around?

A propane retailer can take advantage of the low prices for sales he will make over the next month or two. Unfortunately, demand is waning in these months, especially with the mild weather. It would be far better to have that same price available next winter. Actually, retailers could take swap positions each month from now until winter that would allow them to have near the current price next winter. There would be transaction costs, but the retailer would have a cost of propane under 30 cents at the start of winter. That is still a bonny price.

We are not going to try to explain that process here in Trader’s Corner for fear of being accused of practicing voodoo economics. It isn’t magic; it’s basic supply risk management. If you would like us to talk you through the process, let us know.

What we will discuss are the pros and cons of locking down the price of next winter’s propane by using swaps. It’s something most retailers already have a history of doing, but if you don’t, let’s look at the basics of swaps.

Swaps are financial instruments that are used to offset the price change in the value of a commodity, such as propane. By using swaps, just like making a pre-buy, a retailer can know the future cost of propane supply. That knowledge can be very valuable when rolling out fixed-price and budget programs.

Let’s look at an example that will help take some of the mystery out of swaps. As a propane retailer, you are worried about prices going higher and so are your customers. But, further up the propane supply chain, there are producers that are worried about the price going down. Neither of you know what the price of propane will be in the future, which makes doing business and making decisions about hiring employees or adding assets equally hard at both ends of the supply chain.

Thus, both sides have a vested interest in establishing the future price of propane now. What if you went down to the local coffee shop and sat 6 ft. away from your friend who brought another friend to the coffee shop? You all sit at separate tables forming a triangle with 6-ft. sides. Now that everyone is safe, the inevitable subject of propane comes up.

Your friend’s friend produces propane and mentioned he would like to know what he could sell his propane for in the future. You offer that you would like to know what you would have to pay for propane in the future. After a little haggling, you both decide you would be happy with 35-cent propane next winter. Your friend’s friend agrees to sell, and you agree to buy 30,000 gallons of propane at 35 cents during each month from October through March. They may not know it, but these two gentlemen just did a swap.

You may not know a friend’s friend who is a propane producer, but you can be set up with people who do, allowing you to do exactly what is described above. At that moment, the market has determined that propane for next winter should be valued at 35 cents. A propane retailer could enter a swap with a strike price of 35 cents next winter. That is what he will pay no matter where the spot price of propane is next winter.

Obviously, the benefit is that if prices are higher than 35 cents, the retailer won’t have to pay that higher price – he will pay 35 cents. The risk is that propane will be cheaper next winter, and the retailer could have bought it cheaper.

What if the retailer transferred the risk to his customers? What if, when he agreed to buy propane at 35 cents in Mont Belvieu, he added the price differential to his market and a desired margin, and offered the propane to his customers and the customer agreed to the price? In this case, the producer knows his price, the retailer knows his price and the consumer knows her price. Everyone has taken an unknown – the future value of propane – and turned it into a known through the use of a swap.

Is all risk eliminated? Be careful, because that is a trick question. No, it’s not. The price of propane could go down and the customer might be unhappy to be locked into a higher gas cost. The risk to the retailer is that she is upset enough to leave for a competitor. Risk is never really eliminated; it simply takes on a different form.

What if a retailer decides he does not wish to take the risk of losing a customer in that way? He decides to eliminate that risk by not promising to buy propane at a certain price and will simply buy at market prices, add a margin and that is what the customer will pay.

All risk is eliminated, right? Nope. If prices go up and competitors have taken advantage of historically low prices, the retailer could be pricing well above his competitors come winter and risk losing customers as a result. He could lower his price to make sure that doesn’t happen, but he loses margin in the process, risking the viability of his business.

We can’t eliminate risk, only manage it. We must simply ask: What is the greater risk under current conditions? If a retailer concludes he is in a better position to assume downside price risk than upside price risk, then buying a swap is an easy way of eliminating the risk that worries him most.

We must also consider there can be a lot of value for all parties in this supply chain knowing the future price of propane. The producer transfers the risk of lower prices. The retailer locks in a known margin. The consumer is able to establish a budget and avoid the shock of higher prices. Each is managing risk, and that is usually a function of avoiding what we fear most.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how Client Services can enhance your business at (888) 441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.