What to know about propane regulator lock-up

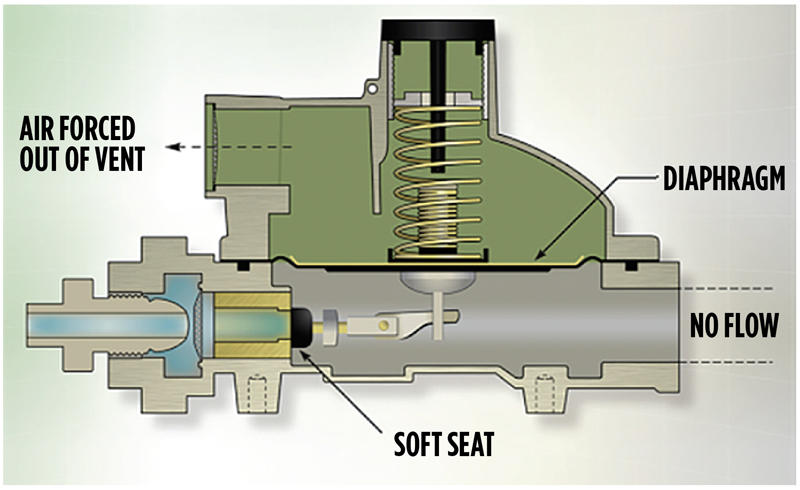

In traditional regulators used in a residential propane system, lock-up is when the regulator orifice is completely closed off, and there is no flow of propane through the regulator.

This occurs when the demand for propane downstream stops. The pressure under the diaphragm builds, pushing up and compressing the main spring. The compression of the spring rotates the lever arm at the pivot point, pushing the seat against the orifice to stop the flow of propane.

Service technicians test to ensure a regulator is locking up by measuring the pressure downstream of the regulator with a manometer or pressure gauge. The test is conducted by introducing propane flow to the system and closing the flow to all downstream appliances. The technician then monitors the testing equipment for the increase in pressure. Once it stops, it is referenced to ensure it has not gone above the acceptable limit. Many companies establish policies around this process and the limits.

Standards

Manufacturers must follow the UL Standard for Safety LP-Gas Regulators, UL 144, when producing a regulator. It provides the lock-up pressure limits based on the type of regulator, the initial inlet pressure, the initial outlet pressure setting, the lock-up pressure limit, the maximum inlet pressure and the lock-up pressure limit at maximum inlet pressure.

The example I use here is a second-stage regulator with an inlet pressure of 10 psig and an outlet pressure setting of 11 in. water column (W.C.). Its lock-up pressure limit is 120 percent (13.2 in. W.C.), with a maximum inlet pressure of 15 psig and a maximum lock-up pressure of 160 percent (17.6 in. W.C.).

The above are requirements to build a regulator. This does not change the fact that the maximum inlet pressure on an appliance is 14 in. W.C., which underlies the requirement that a lock-up should not exceed 14 in. W.C.

Safety and training

What causes the pressure to be greater than the limit? The most common issue is debris between the orifice and the soft seat. This prevents the valve from fully closing, which does not allow the regulator to lock up. On new installations, it is common to find piping shavings, dirt, mill scale and even excess thread sealant in the regulator. Most regulators have a removable screen at the inlet of the regulator to prevent debris from passing into the regulator orifice and seat disc assembly.

If lock-up is not achieved and the downstream pressure continues to build, the additional safety built into the regulator is the internal relief. An additional spring typically located inside the main spring allows a passage to open when pressure exceeds its set point, which is greater than the maximum lock-up.

UL 144 also provides the manufacturer with the set points on the internal relief, which for the same regulator referenced above is a minimum of 170 percent (18.7 in. W.C.) and a maximum of 300 percent (1.19 psig) of the outlet pressure settings. If the regulator cannot reach lock-up, once the pressure builds, the internal relief will activate, allowing the excess pressure to vent through the regulator vent. This protects the downstream system from being over-pressurized.

Today, many appliances are equipped with electronic ignition, so there is no flow of propane like you would have in a standing pilot light appliance. Appliances with a pilot light would constantly burn a small amount of propane, so the regulator would not lock up. With non-pilot light appliances, the regulator must lock up every time the appliances shut off to ensure there is no flow of propane. This is critical to its operation and overall system safety.

The Propane Education & Research Council (PERC) offers education on regulator operation, including propane regulator lock-up, through its Learning Center.

Related:

- Understand automatic changeover regulators

- Natural gas regulators serve as model for safer propane systems

- Understanding the heart of the propane system

- Second-stage regulators designed for low pressures

Randy Warner is product safety manager for Cavagna North America. He can be reached at randywarner@us.cavagnagroup.com.

NOTE: The opinions and viewpoints expressed herein are solely the author’s and should in no way be interpreted as those of LP Gas magazine or any of its staff members.