OPEC’s role in US propane exports

Trader’s Corner, a weekly partnership with Cost Management Solutions, analyzes propane supply and pricing trends. This week, Mark Rachal, director of research and publications, explains how OPEC helped the United States become the world’s largest propane exporter.

Catch up on last week’s Trader’s Corner here: Outlook for crude and its impact on propane prices

Before June 2010, U.S. propane exports were so low the Energy Information Administration (EIA) didn’t even report them. The United States was still a net importer of propane at the time. When the EIA reported exports that month, they stood at 72,000 barrels per day. That is the equivalent to about 100 railroad tanker loads of propane.

In less than a decade and a half, the United States has become the world’s largest propane exporter. In 2024, the United States averaged 1,757,000 barrels per day (bpd) of propane exports. Most of the exports are waterborne. There are now ships capable of loading over 500,000 barrels of propane in a single cargo.

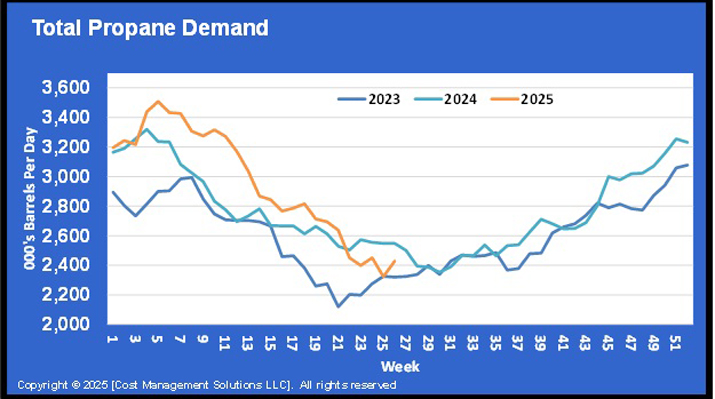

U.S. domestic demand for propane has not been growing. Domestic demand averaged 1.162 million bpd from 2004-2024. Domestic demand has been below that average the last three years. Meanwhile, exports are growing every year.

Recently, exports have been capped by a lack of available export capacity but that is expected to be rectified as new export capacity becomes available in 2025 and 2026. Export capacity is expected to jump from 1.8 to around 2.4 million bpd when the expansions are completed. This expansion would not be taking place if the builders did not have commitments from foreign buyers.

The rapid growth in U.S. propane supply that provides all this extra propane to export came because crude prices rose high enough to justify producing oil and gas from shale formations. Producing from shale formations is costly, so even though producers knew the potential production from shale formations and had the technology to produce it, the economics of doing so were untenable.

The initial cost of producing crude from shale formation was over $70 per barrel. The cost of production from conventional formations was under $10 per barrel and in places like Saudi Arabia, it was under $5 per barrel.

Prior to 2008, the price of crude was not high enough to justify the cost of production. From 1991 to 2001, WTI crude averaged $20.78 per barrel. As economies emerged, especially China, demand started increasing. Only the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) had the capacity to meet the new demand, and they kept supplies tight to drive up prices.

As demand increased from 2002 to 2008, and with OPEC limiting its production, WTI crude averaged $52.41 per barrel, with the average price in 2008 reaching $99.69 per barrel. At this point, the economics were in place to produce from shale formations and the “shale revolution” began.

OPEC fed the shale revolution by cutting back its production to accommodate the new shale production so that crude prices would remain high. They had become addicted to the higher prices. The price of WTI averaged $86.96 from 2009 to 2014. By the end of 2014 U.S. crude production had grown from lows of around 5 million bpd to over 9 million bpd by year’s end. Also, the cost of production from shale formations was coming down due to technological innovation and economies of scale.

OPEC realized the error in cutting its production to accommodate the new shale production. It has tried to put the shale genie back in the bottle but to date it still hasn’t been unable to do so. They increased production from 2015 to 2020 trying to put high-cost shale producers out of business. That drove the price of WTI down to an average of $50.76 per barrel during that period. It averaged under $40 in 2020 during the height of the COVID pandemic. However, OPEC nations had bloated their government budgets when crude prices were high. The low price was hurting them as much as U.S. shale producers. Meanwhile, U.S. crude production hit 13.1 million bpd as COVID began doing what OPEC could not do, slow the shale revolution. Eventually OPEC called uncle and began controlling production again.

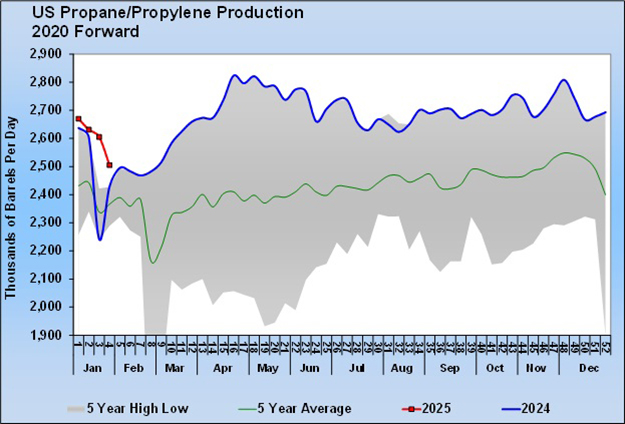

U.S. production is once again above its pre-COVID level averaging 13.261 million bpd in 2024 while OPEC is limiting its production by 5.7 million bpd. Due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, crude prices averaged $93.96 in 2022. To support its member Russia, OPEC+ cut production even though prices were already high. Despite this, crude prices have trended lower the last couple of years and are forecast to be lower yet again this year. OPEC+ keeps postponing production increases to support prices. Once again, they are giving up market share to high-cost shale production by limiting lower-cost conventional production. In this case they limited production when prices were high because of political reasons. Now any indication that they are considering a production increase causes crude’s price to fall.

OPEC touts that its role is to make crude markets fair for both producers and consumers so that the world is well supplied with crude. In that endeavor for the longest time, they stated that a price of between $60 and $70 per barrel was fair for both consumers and producers. But when demand began to increase in the first decade of this century, they were taking actions that were keeping crude averaging around $100 per barrel. That greed opened the door for the shale revolution.

In this decade, they once again stepped away from their stated mission by playing politics lowering production when prices were high. This was to keep crude prices high to help Russian fund its invasion of Ukraine. It was an invasion that was to last weeks and it has lasted years. We suspect OPEC+ is regretting the unnecessary decision to cut production to support Russia. Doing so allowed the recovery of the U.S. shale production that had dropped during the COVID pandemic.

In our view, OPEC has been its own worst enemy. In a free market there is no way low-cost OPEC conventional production would be cut back to make room for much higher cost production from shale formations. OPEC’s production would always be in the lead and U.S shale production would be delegated to supplying any shortfall. COVID almost put the genie back in the bottle, realigning global supply the way it should be – low-cost conventional production as the base and high-cost shale production as the swing supply. But OPEC decided to play politics instead and dropped the cork to the genie’s bottle.

So, the shale revolution continues. U.S. natural gas, crude and propane production is increasing and so is our status as the world’s leading propane exporter. One could argue that if OPEC never existed, allowing crude to be produced and traded unmanipulated, that the shale revolution may have never begun. In which case, the United States would likely be so dependent on foreign supply that it could have far less say on the world stage than it currently enjoys.

To subscribe to LP Gas’ weekly Trader’s Corner e-newsletter, click here.