Settling a financial swap to achieve desired results

Trader’s Corner, a weekly partnership with Cost Management Solutions, analyzes propane supply and pricing trends. This week, Mark Rachal, director of research and publications, explains best practices for using financial swaps.

In our last Trader’s Corner, a propane retailer had just completed a fixed-priced supply agreement with an industrial, commercial or municipal account using a financial swap.

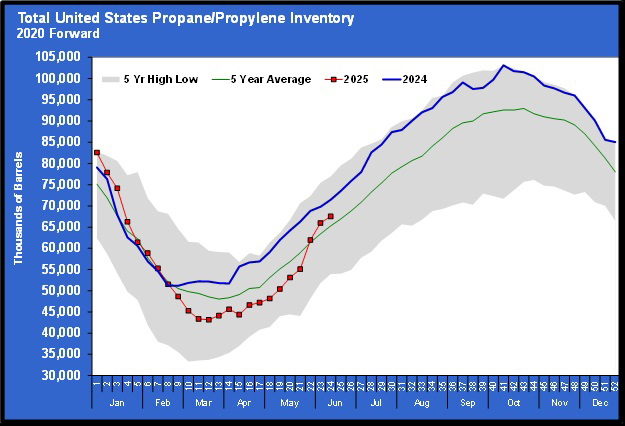

Chart: Cost Management Solutions

In this Trader’s Corner, we are going to go through the process of delivering the physical supply to the customer and settling the swap to see how they work together to provide the desired result.

The retailer bought from his physical supplier at the Mont Belvieu daily average on the day of lifting plus a set differential of 8.5 cents. He also established a trucking rate from the pipeline terminal to his bulk tank of 4 cents per gallon. These are knowns.

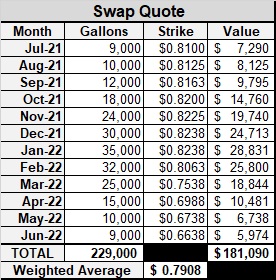

He then entered into a series of 12 swap agreements that match the months and volume needs of his new customer, which turned his supply cost into a known.

Even though the price for each month’s swap is different, he simplified the quote by using a weighted average price of $0.7908, giving one sales price for the entire agreement to his customer. He also set the strike price with his counterparty on swaps at that weighted average price, so each swap will settle against a strike of $0.7908.

A price could have been quoted to the customer for each individual month, and the strike for a particular month in the table above could have been used to settle with the counterparty, but, most of the time, these type of clients prefer an average price over the span of the supply agreement.

Below is the price quote to the customer.

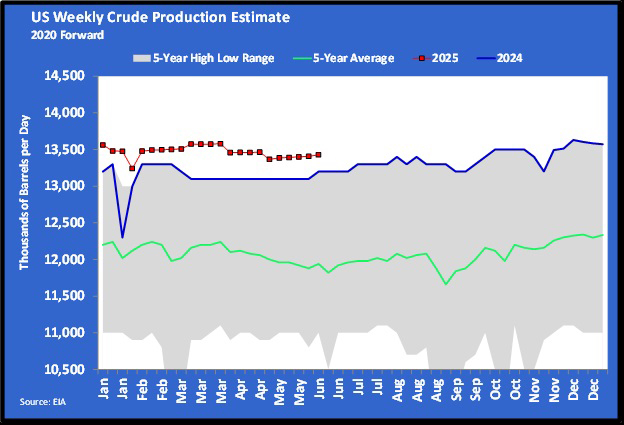

Chart: Cost Management Solutions

Now, let’s go through the process of getting our physical propane for the month of July, delivering it to the customer, paying for our supply, billing our customer and settling our swap.

On July 15, the retailer calls his trucking company and asks it to pull a load of propane off his index account at the pipeline terminal. The propane is delivered to the bulk tank that day. In this case, the retailer is delivering propane to his customer by bobtail over the course of the month.

On July 16, the retailer gets a bill from his supplier based on the daily average price of propane on the day of lifting (July 15) plus 8.5 cents (set differential). Let’s say the daily average price on July 15 was 82 cents, so the bill is for 90.5 cents on 9,000 gallons.

The retailer pays the supplier, and, because the price of propane is higher than the price used to calculate the $1.70 fixed sales price to the customer, the physical activity produces less margin than expected. Remember, we had padded the margin some for a contingency we will discuss later. With that contingency built in, the budgeted margin was $0.7842, but also keep in mind the desired margin was $0.75.

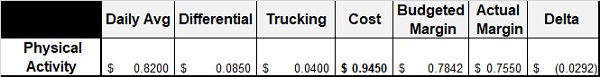

Below is what the accounting of the physical activity would look like.

Chart: Cost Management Solutions

Since the price to the customer was fixed at $1.70, the increase in propane’s price lowered the margin by 2.92 cents.

At the end of the month when the monthly average is known, the financial swap will settle. For simplicity’s sake, let’s assume the monthly average for July was 82 cents, the same as the daily average on the day the physical supply was lifted.

When the swap settles, the monthly average is compared to the strike price, which was $0.7908. If the monthly average is greater than the strike price, which is the case here, the retailer will receive the difference. The difference is $0.0292. The counterparty will send the retailer a check for $0.0292 x 9,000 gallons.

This swap check counters the $0.0292 increase in the cost of the physical propane, returning the margin to $0.7842. Remember, the retailer wanted a $0.75 margin, so, at this point, he is ahead of budget when the combined physical activity and swap payment is considered.

Now is a good time to discuss why this contingency or extra margin was put in place. It was put in place because of the low volume desired by the retailer’s customer. It only took one transport load of propane to cover all of the physical supply needed. That supply was delivered on July 15, and the supply cost was set on that day.

However, the swap settles against the monthly average, which is all of the daily averages in the month combined. The odds of the monthly average for July and the daily average for July 15 being the same are almost zero. It would be just our luck that July 15 was the highest daily average for the month, and the actual monthly average was lower than the 82-cent average for that day.

Now, it could go the other way if July 15 was the lowest price of the month and the monthly average was higher, which means the margin increases for that month. In the higher volume months where several transport loads are being pulled over the course of the month, the odds are much greater that our physical supply cost and the monthly average will be close. And over the length of a 12-month agreement like this one, there would be months where the difference between the monthly average and price of physical supply would be to our advantage as often as to our disadvantage.

Nonetheless, it is important that the retailer knows about the possibility of the difference so the contingency can be built in if desired. Again, this issue applies to very small volumes and is negligible on larger volumes.

In our next Trader’s Corner, we will look at an example where physical propane prices turn out to be below budget.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how client services can enhance your business at 888-441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.