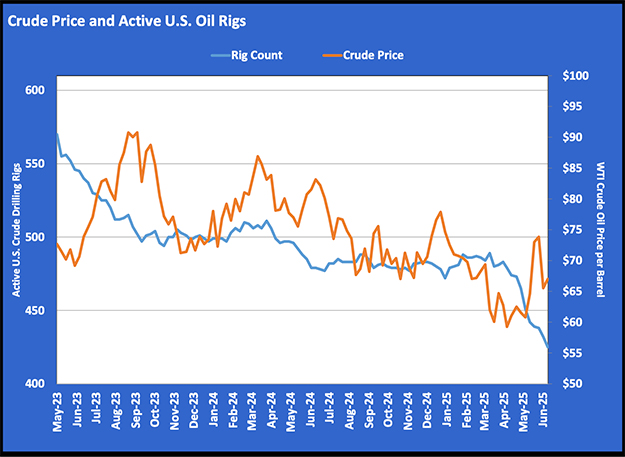

US may become swing producer due to shifting crude prices

In last week’s Trader’s Corner, we answered the question on whether crude prices could go lower. We said yes, which turned out to be the right answer. Following another 25 percent loss on Wednesday, West Texas Intermediate dropped all the way to $20.06. The price of crude has rebounded a little since, but the potential for it to go lower is still present due to demand destruction from COVID-19 and producers not cooperating to limit production. There are no indications at this point that either of those conditions have changed.

In this Trader’s Corner, we are following up on last week’s topic with particular focus on what all of this could mean for U.S. crude production companies, especially those focused on producing from shale formations.

Supplies from U.S. shale producers are almost certain to decline, but it will likely be slowly. Last week, the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated that United States production grew; even though capital spending is being slashed, it could be months before there is significant decline in United States production unless companies close wells simply to save reserves and not sell their crude at a loss. But there are loans, investors and expenses to be paid, so producers may not feel that voluntarily shutting down production is an option regardless of the price that crude is fetching.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia is forging ahead with its survival-of-the-fittest strategy. Saudi Arabia’s cost to produce a barrel of crude is around $3, so it can actually make money at current prices. But that is hardly the concern. Its bigger concern is generating enough revenue to support government budgets dependent on higher crude prices. There is a report that provides more insight into the situation Saudi Arabia faces as it tries to punish other producers for not cooperating with it.

The report says that the Saudi government has been operating at a budget deficit since crude prices plunged in 2014. Back then, it needed about $76 per barrel of crude to balance its budget. This year, it announced a $272 billion budget, which would require $60 crude. It just announced it is cutting government programs by 5 percent. That still leaves it operating at a substantial budget deficit. Even $30 crude, which it says it can live with, would mean a budget deficit of 22.1 percent, according to the report.

Saudi Arabia could find itself in the same situation it did in 2016 when it changed from the survival-of-the-fittest strategy it had employed from November 2014 back to controlling production to support prices. The survival-of-the-fittest strategy hurt it as much as anyone.

Saudi Arabia understands the long-term implications of low crude prices to its economy and government budget. Thus, it initially appears to be making a short-term gambit that will cause other producers to more equitably share in crude price support measures, unless it really believes it can crush U.S. production enough over the next year or two to offset all the increased supply from itself and other producers. It lost that same gambit between 2014 and 2016, but it is possible it sees the U.S. oil industry as more vulnerable this time around. We wouldn’t disagree with that assessment.

Even before this crisis, investment dollars to United States producers operating primarily in shale formations were drying up due to a lack of investor return, which has been going on for over a decade. Many of these companies are also highly leveraged, causing a lot of distress for financial institutions under current conditions. Lenders may resist exposure to this segment in the future. If capital dries up, so does drilling and production.

There are some developments showing that governments are recognizing the threat to the nation’s energy industry. Probably the biggest new development are reports that Texas regulators may curb crude oil output. These reports follow the U.S. federal government’s announcement that it is going to buy 30 million barrels of crude from small to midsized producers for the nation’s strategic petroleum reserve. There are reports that the United States is pushing other producer nations to come together to limit production. There are reports that U.S. oil regulators scheduled talks with OPEC. It would seem the only viable proposal those regulators could make is to join other producer nations in controlling crude supplies.

It is an interesting turn of events. Suddenly the pressure has shifted to the United States to take actions to try and save its oil companies by supporting prices. This must be music to Saudi Arabia’s and Russia’s ears and likely encourages them to continue on their present course.

U.S. shale producers need $40 crude to break even. Probably less than 40 percent of production is hedged in a way that producers can cover that break-even cost. Companies are slashing capital spending programs, but as we mentioned above, the corresponding decrease in production could be several months down the road. The pressure to regulate production is the realization that many companies may not survive if prices stay below $40 per barrel.

The United States has had unbridled increases in crude production since 2008, laughing as it forced OPEC and other producers such as Russia to cut back on production to support prices. Essentially, other producers were forced to subsidize the U.S. crude industry.

Now it appears the shoe may be switching to the other foot. Perhaps the United States is going to become the world’s swing producer. We also speculated on that possibility in a Trader’s Corner we did on Aug. 31, 2015. Here is what we said then:

Historically OPEC had been the world’s swing producer, meaning it would adjust its production to help balance the world’s crude supply with demand as a way to support prices. But, based on past experience and the rate of growth in U.S. and Canadian crude production, OPEC realized lowering its production would simply mean giving up market share to other producers. Its decision to increase production caused the second phase of crude devaluation.

OPEC thought that in the short term it could use its significant production cost advantage to drive high-cost producers in the United States out of the market. … At this point, OPEC is winning the battle, but it may be losing the war.

Indeed, OPEC did lose that war, having to revert to the world’s swing producers again as a matter of self-preservation. It had to begrudgingly allow U.S. companies to produce unabated and do its best to adapt its production so prices would not collapse.

In reality, the higher-cost production should have always served the role of swing supply. Once again, there is a possibility of a new era where lower-cost producers are the base load for crude supply, and the United States and other high-cost producers will take on the swing role once held by OPEC. It would certainly be a remarkable turn of events.

I am sure that other producers are going to relish any overtures by the United States to get them to curb production. They have begged U.S. producers to show constraint and were ignored. Now it is the United States begging them to show constraint. At this point we should not be surprised if they ignore the pleas of the United States. They may be willing to take some pain to see if they can force the paradigm shift they have long wanted concerning U.S. crude production’s place in the crude supply hierarchy.

What does this all mean for the propane industry? The growth in crude supply and the associated natural gas production has caused a major oversupply in propane, which has driven its price down to modern-day lows. If the United States becomes the world’s swing producer, its production rate may be reduced or at the least its growth slowed. That could mean lower propane supplies and higher prices down the road.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how Client Services can enhance your business at (888) 441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.