Use swaps, pre-buys and physicals to manage risk

Trader’s Corner, a weekly partnership with Cost Management Solutions, analyzes propane supply and pricing trends. This week, Mark Rachal, director of research and publications, examines the different types of hedging tools.

Catch up on last week’s Trader’s Corner here: Surge in propane supply doesn’t eliminate risks in logistics

This week, we had a conversation with a client on ideas of when we might use various types of hedging tools. We decided to share some of those thoughts in this week’s Trader’s Corner.

We will discuss three different tools that propane retailers use to manage supply side risk. Terminology can vary, so let’s begin by defining these tools.

Swap:

- It is a financial instrument used to offset the price movement in a commodity.

- For our discussion, the key feature we want to highlight is that it settles against the monthly average.

- A swap is priced at a trading hub such as Conway or Mont Belvieu. That means the differential between the hub and the retailer’s location needs to be considered when setting the price to customers.

- When entering a swap, a retailer can buy or sell. Most of the time, retailers are trying to protect against rising prices, so they buy swaps.

- When buying a swap in the present, the buyer will establish a strike price based on where the market is currently valuing propane for a particular point in time. For example, as we write, the market has January 2025 Mont Belvieu propane valued at 82.375 cents. That would be the strike price of the swap.

- The swap will settle against the monthly average for propane for the month of January once that is known. Each trading day, a daily price average is established, and those are averaged at the end of the month to get the monthly average. Swaps settle against that monthly price average.

- If the month average is higher than the strike, the buyer would get the difference. Let’s say a buyer of a swap chooses 50,000 gallons with a strike of 82.375 cents, and the month average turns out to be 87.375. The buyer would receive 5 cents per gallon or a payment of $2,000 on a 50,000-gallon position.

- In the case above, the retailer would be paying 5 cents more for the propane from their wholesaler in January than what prices were in November. But the $2,000 payment on the swap will offset the increase.

- Swaps are month and volume specific. So, to cover an October-to-March winter, a buyer would hold six swaps, one for each month.

- Buyers can close swaps early if market conditions change.

- Swaps can be established for as much as three years out. For example, it is currently possible to establish a price each month for as far out as October 2027.

Pre-buy:

- A pre-buy is bought from the wholesaler and is priced at a delivery point, usually a pipeline terminal. That means the price would include the wholesaler’s margin and pipeline tariffs.

- Today there are usually two types of pre-buys to choose from – ratable and non-ratable.

- A ratable pre-buy works much like a swap where the buyer pulls a specific volume each month.

- A non-ratable pre-buy has a volume for the winter period, and the buyer can pull the volume anytime during the winter period they need it. Because of this flexibility, a non-ratable pre-buy is higher than a ratable pre-buy.

- There is no settlement with pre-buys like there are with swaps. A retailer would generally have a separate pre-buy account at a pipeline terminal from his posted price account. The retailer simply tells the trucking company picking up the propane whether to pull product from the spot or posted price account or the fixed-priced pre-buy account.

- A pre-buy is harder to close and is usually done by using a swap. To close a pre-buy position, the buyer would sell a swap for equal volumes. The swap sell would counter market price movements, essentially locking in the current gain or loss on the pre-buy position.

- Pre-buys are generally only available for the upcoming 12 months.

Swaps and non-ratable pre-buys are usually used together to take advantage of each one’s strength. More on this in a moment, but let’s look at the features of the last tool first.

Physicals:

- Physicals are also a financial tool (though the terminology would lead you to believe otherwise). Logically, when we think physical, we think physically moving consumable propane molecules, but that is not what is happening here.

- Most of everything we said about propane swaps would apply to propane physicals, with one primary difference. Physicals do not settle against the month average. The buyer of a physical chooses the day of the month to exit the position.

- Impacted by bid/offer spreads (more on this later).

- Usually used when delivery of propane happens in a compressed time frame (example later).

With all three tools defined, let’s go through a few examples of how they may be used.

All of these tools are used to mitigate risk associated with supply, with the primary focus of retaining valued customers. The tools are useful as revenue, customer and margin protectors.

When propane prices are low, propane retailers are at reduced risk of losing valued customers to other energy sources or competitors. However, a high-priced environment, where customers are getting high propane bills, can cause them to move to other energy sources and/or other propane suppliers. Any supply risk management strategy should be focused on helping mitigate the risk of losing valued customers in high propane pricing environments.

The balance to this endeavor is that the retailer must guard against taking on too much price protection that would put them at a competitive disadvantage in a falling or low-priced environment.

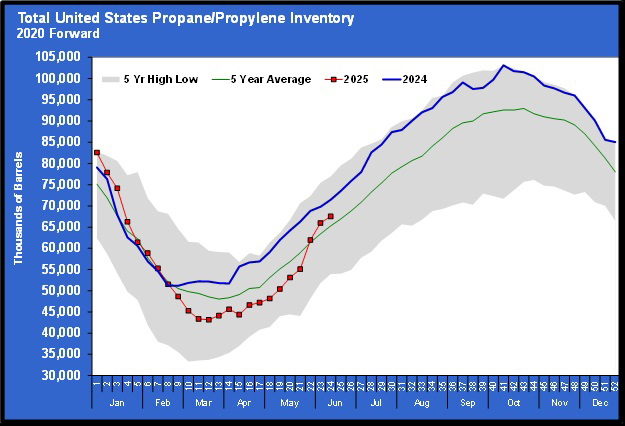

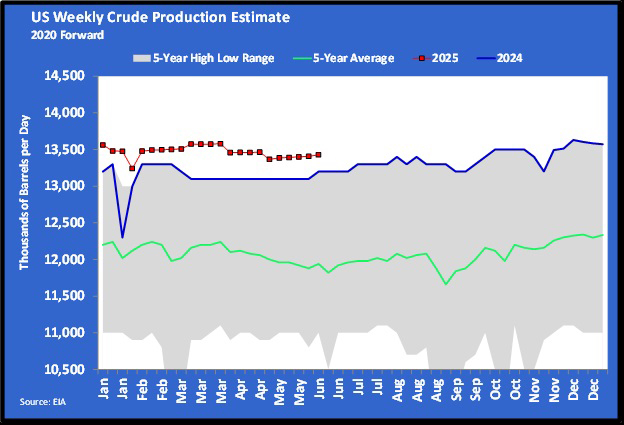

As a propane retailer considers price protection for an upcoming season, they may go in with a standard of getting price protection on 40 percent of their sales volume. If propane is well supplied, the percentage would go down. If propane appears undersupplied, that percentage might go up, but only if the market gives the buyer opportunities to set the price protection at favorable values.

Favorable values would be somewhere below the long-term average prices for propane. For example, propane in Mont Belvieu has averaged 78.5 cents during the winter months over the last ten years. The goal would always be to establish winter price protection below that average. One of the great advantages of using swaps is that the buy window is so much longer (three years) than with a pre-buy (one year), increasing the opportunity to buy at a favorable price.

The swap and the non-ratable pre-buy would be the tools of choice for establishing price protection. Let’s say a retailer is going to fix the price on 40 percent of their sales volume for the winter, and that turns out to be 700,000 gallons.

Let’s say that 600,000 gallons of that protection is done by purchasing six swaps – 100,000 gallons of volume each month from October through March. The remaining 100,000 gallons would be a non-ratable pre-buy with some or all of that volume to be pulled at anytime during the winter that the retailer desires.

The retailer will be buying 60 percent of their winter needs at posted or spot prices over the course of the winter and 40 percent at fixed prices based on the strikes of the swaps and pre-buys. The buyers would average these costs, adding the desired margin to establish the price charged to customers.

In a low-priced environment, the price protection will be a drag, causing the retailer to charge more than if they were just buying all of their supply in the spot market. But hopefully the 40 percent volume at the fixed price is not so much as to put the retailer at a harmful disadvantage to a competitor that has no price protection. Again, our strong belief is that during low-priced environments, even if a retailer’s price is above a competitor’s, propane bills received by the consumer will be palatable, reducing the chances they will be motivated to make a change.

In a high-priced environment, the retailer with price protection uses it to mitigate some of the shock the customer is going to get on their next bill. It may still be a high bill since 60 percent of the cost will be based on the high spot market prices, but hopefully the price protection will be enough that if the consumer does “shop” their retailer, they will find that the price is good relative to the competition, thus reducing the motivation to make a change.

Let’s say a winter storm hits in the month of November, and propane prices in the spot market surge. The 100,000 November swap is going to mitigate some of the price increase. However, the retailer may not think it is enough. He has the non-ratable pre-buy in his pocket and decides to pull all of that volume in November to avoid buying 100,000 gallons in the high spot market. Combined with the base swap protection, the flexible non-ratable pre-buy protection gives the retailer an improved chance of retaining customers in a high-priced situation.

Physicals are best used when propane is delivered to a consumer in a short period of time rather than over the course of a full month. Let’s say a retailer has a commercial account that buys a large volume of propane, but they have it all delivered in the first week of the month. If a retailer uses a swap that settles on the month average to establish the price to the consumer, a drop in propane prices after that first week will hurt the retailer’s margin.

A better tool would be a physical that the retailer can settle on the day of the month he chooses. So, the retailer delivers propane to the consumer during the first week of the month and during that same week closes his physical position that was taken to establish the price to the customer. Propane delivery and financial activity are now much better matched, reducing risk to the retailer’s margin.

To close a physical buy, a retailer must sell a corresponding volume. When buying swaps or physicals, the strike is based on what propane is being offered for in the market. Offers are the prices that sellers are saying they are willing to take.

When selling, the strike is based on the bids at the time of the transaction. Bids are based on what buyers say they will pay. Since propane is a thinly traded market, it is not unusual to see a bid/offer spread of a penny or more. A retailer using physicals is subject to the bid/offer spread risk, but that may be less than the risk of using a swap that settles weeks after the delivery of the propane.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how client services can enhance your business at 888-441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.