Closing propane forward positions

Trader’s Corner, a weekly partnership with Cost Management Solutions, analyzes propane supply and pricing trends. This week, Mark Rachal, director of research and publications, discusses the process of closing propane forward positions.

Catch up on last week’s Trader’s Corner here: Propane market reacts as feared

In last week’s Trader’s Corner, we discussed the jump in propane prices and expressed concern that, once the current weather passes, the price gains will be given back. The surge in prices continued as the cold front passed across the nation. The rise in prices caused some of our clients to close forward positions.

A forward, commonly known as a swap, is a financial tool used to offset price moves in the physical market, allowing the holder of the forward to have a known cost of supply in a future month. In that respect, it functions very much like a prebuy that a propane retailer would make with his physical supplier.

In this Trader’s Corner, we will look at why the clients made this decision, how a forward position is closed and the frustrating aspect of closing a propane forward position.

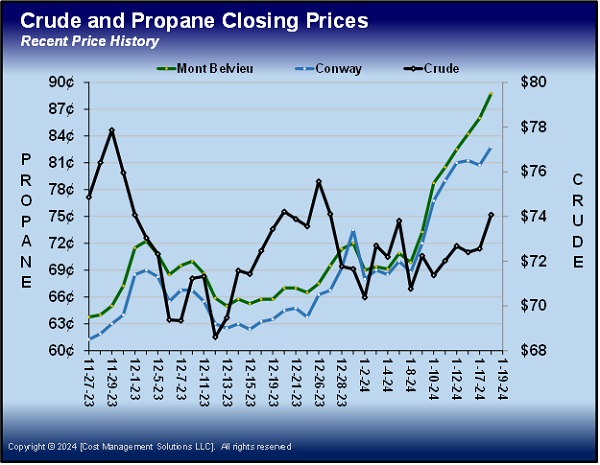

Chart 1 shows the opportunity that the holder of a forward was given.

Propane prices had been weak. High inventories resulted from robust production and slow demand, especially in the domestic markets, due to the mild winter to date. But inventory positions had recently tightened, propane had remained undervalued, and the cold front essentially jolted the market out of its slumber. As a result, in just seven trading days, Mont Belvieu ETR propane jumped 18.875 cents. Conway rallied 14 cents. Prices continued to surge as of Jan. 19.

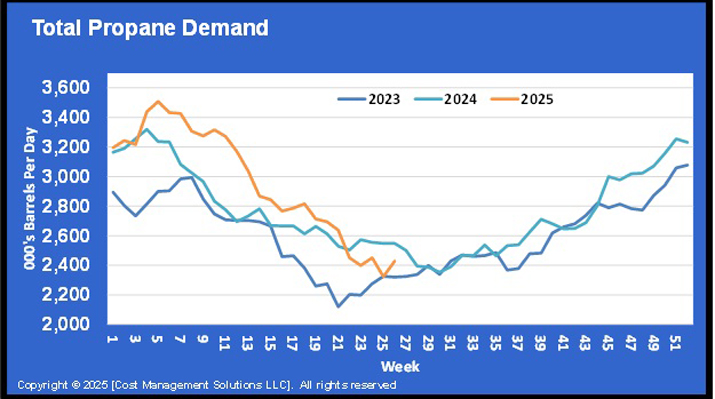

Now, for the basis of the decision to close: In most cases, a jump in prices would be a reason to hold forward positions. A key reason for taking forwards, doing prebuys or filling storage is to protect against this exact kind of spike in prices. Clients decide to close because the increase in prices is likely not sustainable.

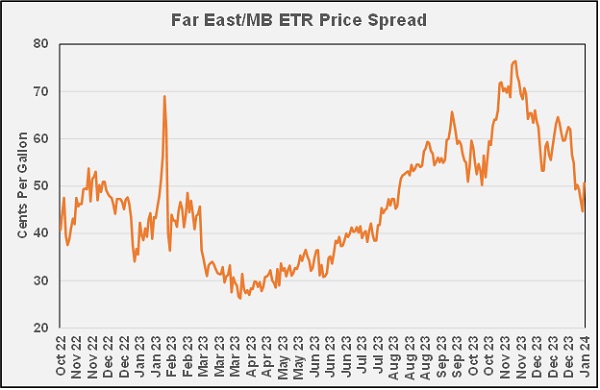

In last week’s Trader’s Corner, we showed Chart 2.

It shows that export economics or the arbitrage opportunity to move propane from the U.S. to Asia is becoming less favorable. Demand in Asia is off, so the way to keep exports going will be for U.S. prices to fall. On most days, the U.S. exports more propane than it consumes, so keeping supply and demand balanced is highly dependent on exports.

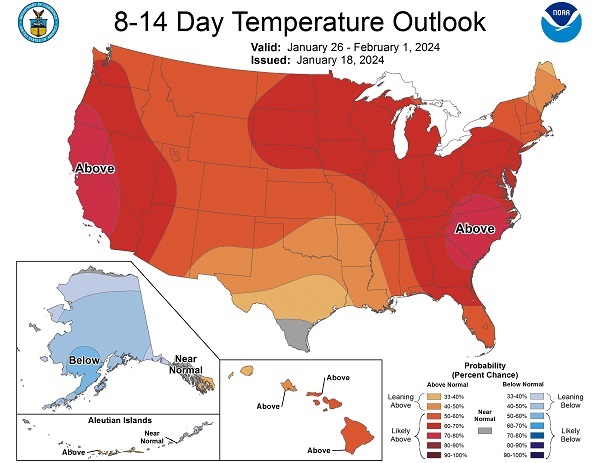

It also does not look like the current weather support will continue. Chart 3 shows a high probability that most of the nation will experience above-normal temperatures by the end of the month.

We also know that the current spike in prices has a lot more to do with disruptions to propane supply at Mont Belvieu than it does with demand. While demand is better, propane inventories are still in good shape for this time of year. But low temperatures wreak havoc on oil and gas production, natural gas liquids fraction, storage facilities management, crude refining, transportation and just about every other aspect of the energy supply chain. As temperatures warm, operations will get back to normal quickly, taking away much of the reason for the current craziness in propane prices.

How to close a position

Now that we know the opportunity and the basis for closing forwards, let’s look at how to close a position. Our clients originally bought forward positions to protect against higher prices. When you buy a forward, you get a strike price that is based on propane’s value for some month in the future on the day the forward was bought. When that month comes and goes, the average price for propane throughout that month is known. If there are 21 trading days in a month, the high and low price for each of those days is averaged to get the daily average, and those are averaged to get the monthly average. If the monthly average is higher than the strike price of the forward, the holder of the forward receives a payment for the difference from his counterparty. This payment offsets the rise in propane prices from the time the forward was bought through the month it was bought to cover. Knowing the payment will come should prices go up is what allows a buyer of a forward to fix prices for their customers now for a month in the future.

On the other hand, if prices go down, and the monthly average is below the strike prices of the forward, the buyer of the forward contract will have to pay the difference. For this reason, a retailer that holds a forward should base their price to the consumer on the strike price of the forward, not market prices during the month for which the forward is bought. Because propane prices are lower, the retailer will pay less to their supplier for the physical propane delivered to customers that month. But if the retailer lowers their price to the consumer, they will not have the funds to make the payment on the forward without hurting the margin. This is no different than if a retailer used a prebuy or filled storage to protect against higher prices.

To close a forward position, a retailer simply sells a forward for the same month and volume that they originally bought. Let’s say in June a retailer buys a forward December at a volume of 10,000 gallons with a strike price of 75 cents. In October, he decides he no longer needs that price protection, so he sells a forward December with a volume of 10,000 gallons. The two positions now offset each other. Both will settle at the end of December, but whatever gain or loss had occurred on the original buy is locked in. Let’s say the sale had a strike of 70 cents, then a 5-cent loss was locked in. If the strike of the sale was 80 cents, a 5-cent gain was locked in. The ease with which positions can be opened and closed is one of the key benefits of using forwards.

A frustrating aspect of closing propane forward positions is that the bid/offer spread can be wide. When a retailer buys a forward, the strike is based on the offers. A trader offers propane for sale, and a retailer takes the best offer available when they buy the forward. Bids are what traders are willing to pay for propane. When a trader sells a forward to close, the strike is based on the best bid. Because propane is a rather thinly traded commodity, the spread between bids and offers is generally in the 1-cent to 2-cent-per-gallon range in a stable market. If a retailer bought a forward one minute and sold it the next, he would likely experience a 1-cent to 2-cent loss.

In our current price spike situation, propane markets are under a lot of stress and uncertainty, and the bid/offer spread reflects that fact. Because of the uncertainty, traders don’t want to buy propane. They realize it is likely to fall soon and could be significant when it does. They are in the same situation as the retailer, wanting to sell, not buy, propane. As we look at the trading screen (9:47 a.m., Jan. 19), the bid/offer spread at Conway is 1 cent, about normal. However, the bid/offer spread at Mont Belvieu ETR is 8 cents. But consider that Conway is bid at 81 cents and Mont Belvieu ETR at 84 cents. Even with the big bid/offer spread, Mont Belvieu is still holding a premium.

If the current spike in prices was related to sustainable demand due to long-term cold weather or strong export demand, the bid/offer spread would be much closer, even with prices rising sharply. But, again, this is a unique situation related to supply and operational issues at Mont Belvieu that are likely to resolve quickly. The market is simply reflecting that fact. No one wants to be a buyer, and everyone wants to be a seller except the one or few that are causing the spike. Bid/offer spreads get tight when the numbers of buyers and sellers are about equal. But, in situations like this where everyone wants to be sellers and only a few are buyers, the bid/offer spread gets wide.

Unless noted, all charts are courtesy of Cost Management Solutions.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how client services can enhance your business at 888-441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.