How to minimize the unknowns when pricing propane

Trader’s Corner, a weekly partnership with Cost Management Solutions, analyzes propane supply and pricing trends. This week, Mark Rachal, director of research and publications, evaluates how a propane retailer can determine all the available knowns when pricing propane for the future.

Catch up on last week’s Trader’s Corner here: Imbalances between propane production, export capacity

Former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, at a press conference on Feb. 12, 2002, concerning linking the government of Iraq with weapons of mass destruction, made a statement that became famous:

“Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.”

Propane retailers wanting or needing to lock in propane prices for the future may relate to Rumsfeld’s statement. In this Trader’s Corner, we will try and capture some things we know as propane buyers and some things we may not know now but could, thus reducing the number of unknowns to one. There could still be unknown unknowns, as Rumsfeld famously refers to them, but we must deal with those should they become known.

Retailers know they have customers who will demand propane from them in the future. Based on their sales history, retailers probably have a feel for the minimum and maximum volumes they are likely to sell, but they can’t know exactly how much they will sell in the future. The best way to deal with the unknown volume is not to overbuy. Hedging and price protection should be calculated beginning with the lowest potential sales volume.

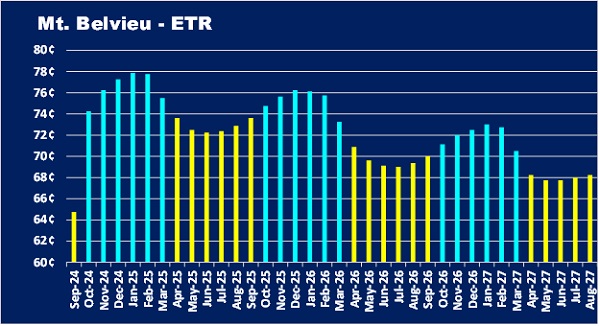

Retailers know the current price of propane for not only the current month but also three years out.

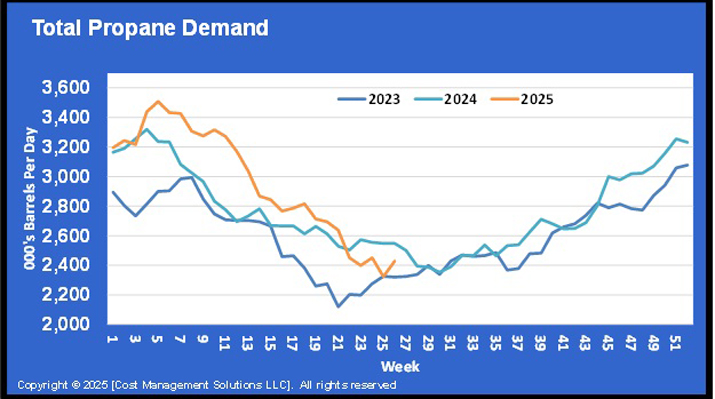

Chart 1: Mont Belvieu – ETR – September 2024 through August 2027 (Courtesy of Cost Management Solutions)

Chart 1 is a recent forward price curve for propane. These were known prices based on the buying-selling activity at that moment, and a propane buyer could have bought propane at around those prices for each month shown at that time.

Without any future price protection from swaps, pre-buys and/or filling storage, a retailer has little idea what he will pay for propane when his customers demand it at some point in the future. That unknown can be turned into a known.

To make it easy to follow the points we want to make in this Trader’s Corner, let’s focus on the price of propane for just one month. January 2025, propane was valued at 78 cents when Chart 1 was captured. Let’s say a retailer did a 50,000-gallon swap at that price.

With that swap in hand, the retailer eliminated one unknown, namely his cost for the 50,000 gallons of propane that he expects his customers to demand in January 2025. What the actual market price for propane will be in January 2025 is still unknown and will remain so until January comes and goes.

Succinctly, a propane retailer has created a known supply cost in Mont Belvieu, Texas, on 50,000 gallons of January 2025 propane using a swap to offset market price movements.

Retailers also know that the price of propane in their tank is valued higher than the price of propane at Mont Belvieu. They see the difference as related to two things: transportation costs and the wholesale margin the physical supplier adds to the propane for its services. They are two pieces to the transportation part. The first is what the pipeline company will charge to move the propane from Mont Belvieu to the terminal up the line that a trucking company uses to get the retailer his physical propane.

What the pipeline company charges to move products along its pipeline is called a tariff. The tariff is known or is at least knowable. Pipeline companies are required to publish their tariffs so any user of its line will know exactly what it costs to move propane from Mont Belvieu, Texas, to a specific terminal up the pipeline. Let’s say a retailer looks up the tariff to the terminal, where he will send the trucking company to pick up his physical supply and finds it is 8 cents per gallon.

The swap buyer knows that no matter what the price of propane actually is in January, the swap he owns will offset market movements, resulting in cost of supply of 78 cents on 50,000 gallons. He knows the cost of getting the propane to the terminal is 8 cents, making his propane at that point 86 cents. Another piece of the pricing puzzle at the terminal is unknown. That is the amount the physical supplier will add to the propane for his margin.

Physical suppliers will post propane for sale at a certain delivery point. Unless the retailer knows both the price of propane at Mont Belvieu when he has the propane lifted and the tariff, he will have no idea what margin the wholesaler has added. Ideally, propane retailers can change that unknown into a known. Perhaps propane wholesalers add 2 to 5 cents margin, with it varying for the year. It would be preferable to negotiate what is known as an index contract with the physical supplier that fixes the margin amount.

The price paid on an index contract is indexed against the hub price connected to the pipeline terminal, Mont Belvieu or Conway. Let’s say the physical supplier and retailer negotiate an index contract that fixes the wholesaler margin at 3 cents. The pipeline tariff from the hub is 8 cents in our example. That makes the difference between the hub and the pipeline terminal 11 cents. That is now a fixed number. An example of an indexed contract would be the propane retailer paying the daily average for Mont Belvieu TET propane on the day of lifting (the index) plus 11 cents (the fixed differential).

The retailer and wholesaler might agree on a different index, for example using the monthly average instead of the daily average or using a different pricing point like Mont Belvieu non-TET propane rather than Mont Belvieu TET. In any case, eliminating another unknown is important for the retailer by fixing the wholesale margin amount.

The last leg of the pricing is the transportation from the pipeline terminal to the retailer’s tank. Ideally, a retailer would negotiate a long-term freight rate, so this becomes known as well. For our example, let’s assume the freight is negotiated and fixed at 5 cents per gallon over the next year. Adding the freight to the fixed pipeline terminal differential is 16 cents, making the differential between Mont Belvieu or Conway and the retailer’s tank a known 16 cents. A buffer might need to be built into the freight amount, especially when quoting customers a fixed price further out to cover possible increases in the rate. But, for our example, let’s stick with 16 cents.

At this point, a retailer still has no idea what the price of propane will be in January 2025. As we said before, that is destined to remain unknown until January has come and gone, and the monthly average for January 2025 can be calculated.

He knows he has the same favored physical supplier he has been using, which allocates and moves propane up the line to the pipeline terminal he is familiar with using. He also has a favored trucking company that will move propane from the terminal to his tank. He knows what he is going to be charged for those services. This process of moving propane through the supply chain and the cost of doing so is known as the physical side of the transaction.

He knows that he has a 50,000-gallon swap with a strike price of 78 cents in the hub of Mont Belvieu, Texas. The activity surrounding the swap is known as the financial side of the transaction and functions independently of the physical transaction. However, one offsets the other to provide a known cost of supply.

The retailer knows that when January arrives his physical supplier is going to charge him whatever the daily average for Mont Belvieu propane was on the day of lifting plus 11 cents and that the trucking company is going to move it into his tank for 5 more cents, making the total differential 16 cents.

He knows that no matter what the actual price of propane is in January, his swap is going to offset the changes in the cost of the physical propane bought such that the price paid is 78 cents + 16 cents, or 94 cents FOB in his storage tank. He knows he can add his desired margin, say a dollar, to that price and fix a January sales price to his customer at $1.94. With that sale in place, a hedge is completed that establishes and protects the retailer’s margin.

All the pricing components downstream of Mont Belvieu are now known. The swap is at Mont Belvieu, and the physical supply will price against that Mont Belvieu price, so it makes for a clean hedge (minimum number of variances between the physical and financial side of the transactions). The retailer has a swap with a known fixed strike price, a known pipeline tariff and wholesaler margin, a known trucking freight rate, and a known sales price to the customer.

Propane prices are unlikely to remain where they were on the day the swap was set, establishing all the knowns above. First, let’s look at what happens when propane prices go up, which is what the retailer wanted to protect his customers from, and then what happens if prices go down.

We can focus on the price movement at Mont Belvieu since all the rest is fixed. Let’s assume that when January is in the books, the price of propane averaged 90 cents at Mont Belvieu. The physical supplier will invoice the retailer 12 cents higher than what the sales price of $1.94 above was built upon. Yet the retailer will only receive $1.94 from his customer. Therefore, the physical side of the transaction will yield just an 88 cents margin to the retailer, not the desired dollar.

Now, operating completely independently, the swap position settles. The retailer bought a swap with a strike price of 78 cents. As a buyer of the swap, he will receive the difference between the 78-cent strike and the monthly average for January Mont Belvieu propane, which was 90 cents. Our one unknown is now known. The retailer will get a 12 cents-per-gallon payment on 50,000 gallons of propane. That payment, combined with the 88 cents made on the physical transaction, yields a combined gain of $1, which was exactly what the retailer priced and budgeted against.

If propane prices fall and average 70 cents in January, the retailer will make $1.08 on the physical side of the transaction. However, he will be obligated to pay 8 cents on the financial side (swap). He will use the 8 cents extra margin made on the fixed-priced sale to the customer to cover this swap obligation, returning the margin on the combined physical and financial transactions to $1, which is just what was priced and budgeted against.

The example above is a true hedge because the supply costs and the sales price were both known and established. If the sales side is not established and the swap position is taken, it is no longer a hedge; it is speculation. In that case, the sale to the customer does not protect the retailer from falling prices. Removing that one known completely changes the complexion of the situation.

If the retailer could establish the supply side at a very favorable number, he may know he can hold his retail price up even if the market falls. Once the supply was set with the swap, essentially it should be viewed as the sale side being set as well, whether the retailer has a customer committed to the gallons or not. The retailer should see it as committing to a sale at $1.94, whether to a customer that has agreed to it in advance or will call for it in January. If the retailer does not do so and lowers the sales price in the future, he will erode the margin.

No matter what we do, we cannot eliminate the unknown of what propane will be traded for in the future. We might be able to make some educated guesses, but we simply cannot know for sure. Other than some smaller variances in how the physical and financial sides of these transactions operate, we can know the other important components that allow the retailer to change an unknown cost of supply into a known one.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how client services can enhance your business at 888-441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.

Related articles: