Propane production and where it comes from

Trader’s Corner, a weekly partnership with Cost Management Solutions, analyzes propane supply and pricing trends. This week, Mark Rachal, director of research and publications, gives an overview of propane production.

Catch up on last week’s Trader’s Corner here: How propane compares with heating oil

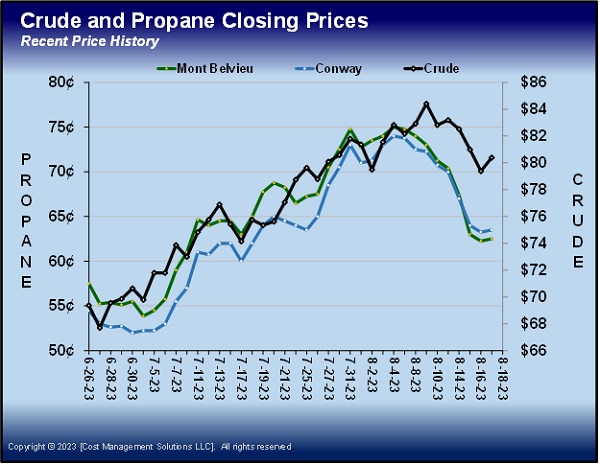

On Aug. 4, when the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) collected data for its Weekly Petroleum Status Report that would be released on Aug. 7, propane had been in a long uptrend, mostly riding the wave of a crude rally but also getting support from lighter-than-normal inventory builds. The rally was showing signs of slowing, but data in that EIA report contributed to ending the propane rally and sending prices into a sharp downtrend.

The data point we refer to is propane production. A few days later, crude prices started falling, adding even more downward pressure on propane prices.

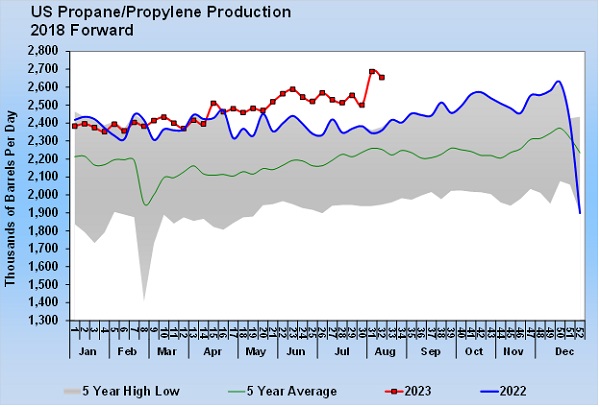

For the week ending Aug. 4, the U.S. produced a record 2.687 million barrels per day (bpd) of propane. It was an enormous increase of 187,000 bpd from the previous week. That kind of production increase could be a game changer for propane fundamentals if sustained. For the week ending Aug. 11, production only dropped off 33,000 bpd. For now, the production increase appears sustainable.

We believe the increase is due to the increased fractionation capacity around Mont Belvieu. When we reported that in our daily Propane Price Insider report, we got some inquiries about propane production. We realized from those discussions the need to review the propane supply chain. It will help clarify why we qualified the statement about propane production by saying it is sustainable for now.

Propane comes from drilling hydrocarbon wells, usually in some remote area of the country. The wells are classified as crude or natural gas depending on whether they produce heavier hydrocarbons (crude) or lighter hydrocarbons (natural gas). An array of hydrocarbons comes from these wells regardless of type.

Near the fields where heavy hydrocarbon wells are drilled, there are separators. In these separators, water settles to the bottom, heavy hydrocarbons are in the middle, and lighter hydrocarbons rise to the top. Each leaves the separator and heads to the next part of the supply chain. The water is generally disposed of in the field, the lighter hydrocarbons head to a natural gas processing plant, and the heavy hydrocarbons go into tanks or pipelines and ultimately end up at a refinery.

Originally, refineries were built all over the country so that, once the crude was refined, the refined fuels would be near a market that needed them. Crude was shipped from production areas to refineries located in demand areas. However, people don’t want refineries near them, and tougher regulations have seen refining capacity become concentrated in areas well away from the refined fuels demand and closer to where the crude is produced. Refined fuels from these centralized refining areas must be shipped via pipeline to areas of demand.

Propane is trapped in the heavier hydrocarbons. When the heavier hydrocarbons are processed, propane is a byproduct of the process that provides gasoline and distillates. Refineries near demand areas generally sell their propane production in the local market. Many propane retailers source some of their propane supply from refineries in their area. Supply options directly from refineries have been declining for retailers because of the centralization of refining that has been occurring for decades. If your retail business has been in operation long enough, there is a good chance that a refinery that was once a source of propane no longer exists in your area. In the centralized refining areas where the propane production exceeds demand, the propane is shipped to markets or to storage via truck, train or pipeline. This leg of the propane supply chain accounts for 12.7 percent of all propane supply.

We need to go back to the fields where heavy and light hydrocarbon wells are produced to pick up the second and largest leg of the propane supply chain. Remember, the separators near heavy hydrocarbon wells separate light hydrocarbons and send those to natural gas processing plants that are often near the production areas. There are probably light hydrocarbon wells nearby, and there are separators near those wells too. The light hydrocarbons usually don’t have much water, but they do have a lot of condensates that come out of the bottom of the separator. The condensate is transferred into the heavy hydrocarbon system we discussed above. The lighter hydrocarbons go to the natural gas processing plant and are likely mixed with light hydrocarbons that originated as associated production with the heavy hydrocarbon wells.

We now have light hydrocarbons from both crude and natural gas wells at the natural gas processing plant. The primary purpose of the natural gas processing plant is to separate out the lightest hydrocarbon, methane, and put it into pipelines that begin the natural gas distribution system in this country. Those pipelines deliver methane to natural gas utility companies that have distribution systems that deliver the methane to end-use customers. Some natural gas processing plants installed the ability to separate propane to sell into the local market if there is demand nearby. Many propane retailers buy propane directly from the natural gas processing plants that have this capability.

However, most of the natural gas liquids that remain after the methane has been removed are transported via pipeline to major hubs that have fractionation and storage facilities. All of us in the propane industry know these very well. The primary ones in the U.S. are Mont Belvieu and Conway. The mixture of natural gas liquids that leaves the natural gas processing plant is generally referred to as Y-grade. The Y-grade goes into large underground salt dome caverns to await processing by the fractionators. It is possible for Y-grade production to exceed fractionation capacity, causing Y-grade inventories to build. When more fractionation capacity is added, as was the case recently, more of all of the various natural gas liquids (ethane, propane, butanes and natural gasolines) can be produced. That is exactly what caused the recent increase in propane production.

This light hydrocarbon leg of the supply chain yields 87.3 percent of propane supply. The propane that is produced at the hubs goes back into storage facilities and is eventually shipped via truck, train or pipeline to end-use markets. Retailers that buy from pipeline terminals are generally getting propane that followed this process.

What is important to consider is that the entire supply chain is driven by the amount of hydrocarbon wells that are being drilled and produced. If enough wells are not drilled and produced once excess Y-grade is processed, the amount of propane supply could go down regardless of how much fractionation capacity is available. That is why we qualified the statement about the new propane production being sustainable. The fractionation capacity to sustain the increase in production seen the last two weeks is now present, but it is still dependent on overall hydrocarbon production.

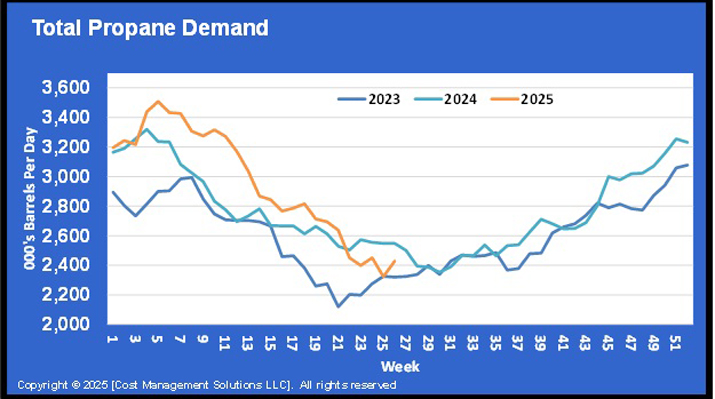

At the same time this new fractionation capacity was added, there were also new propane dehydrogenation plants put into service that will convert propane into propylene used by petrochemicals to make plastics. This is a new source of demand for the new propane supply. The bottom line is the market will have to adapt to these new changes in capacity on both sides of the equation.

When we see such a huge increase in supply, we have doubts that demand will immediately respond to absorb it all. Until we see demand respond, we will be on guard for above-average inventory builds to resume. This past week’s inventory build was below normal, so we really aren’t seeing the full impact of the production increase just yet, but prices have already responded to the production increase by going lower. If inventories start building at an above-average pace, we could see the downward pressure on prices remain until winter demand picks up in earnest.

All charts courtesy of Cost Management Solutions.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how client services can enhance your business at 888-441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.