Solving the mystery of propane forwards

Trader’s Corner, a weekly partnership with Cost Management Solutions, analyzes propane supply and pricing trends. This week, Mark Rachal, director of research and publications, describes how propane forwards function.

Catch up on last week’s Trader’s Corner here: EIA to provide new propane data point

We know that propane forwards, or swaps, remain a bit of a mystery to some of our readers. We use the terms “forwards” and “swaps” interchangeably. We prefer forwards because propane is really operating in the forward market, but the common nomenclature is a swap. In this Trader’s Corner, we are going to show how propane forwards and propane bought from your supplier and stored function the same way. We hope that the example we use will help solve the mystery.

Imagine that a propane retailer has spared no expense and has bought and installed six 30,000-gallon storage tanks at their location. They have named them differently, starting with October and ending with March. Now, let’s imagine it is the beginning of the summer, and they begin to fill the tanks by buying transport loads of propane at their nearest pipeline supply point. The belief is if they fill the tanks over the summer it will either protect their customers from higher prices in the winter or provide them with the opportunity to make a higher sales margin.

In April, they send transport trucks to the pipeline terminal and buy three loads of propane from their favorite supplier, filling the October tank with 30,000 gallons. They are invoiced by the supplier and the transport company. The bills are paid, and a known cost of supply is established for the propane sitting in the October tank. To be fair, the propane tank farm didn’t come free. There was a lot of cost associated with it. The retailer should add an appropriate amount to cover the storage cost and operation.

Consider what is in the cost of that propane. Let’s say the retailer has a contract to buy from the wholesale supplier at whatever the average price of propane is on the day of lifting at Mont Belvieu plus 10 cents. In that 10-cent differential between Mont Belvieu and the pipeline terminal is the pipeline company’s tariff for shipping propane through its system from Mont Belvieu to the terminal. The supplier will have covered other expenses and their wholesale margin. Let’s also say the cost of trucking the propane from the pipeline terminal to the retailer’s October tank is 5 cents. The total difference between Mont Belvieu and the retailer’s tank is 15 cents. To that the storage cost is added.

Through the summer, the retailer repeats the process of filling each tank and establishing a known cost of supply. In this case, the price in each of the six tanks will be slightly different, assuming prices at Mont Belvieu fluctuate over the summer.

Now that propane is bought and in the tank, what is the risk to the propane retailer? The risk is that propane prices will fall between the time the propane was bought and when it will be sold. The only way to avoid this risk is to presale the propane to customers as soon as it is bought in April for October delivery.

To that end, the retailer adds a desired margin and sends letters to customers offering propane for sale for October delivery, and they accept. Now, as the propane sits in the tank from April to October, its cost and sales price are known. The retailer has created a perfect hedge with no risk. The supply cost is fixed, the customer’s price is established and the margin is protected. The retailer would repeat this sales process while filling each tank.

Frankly, the scenario above would be the way to go every time, if possible. The retailer does give up the potential to make a higher margin should prices go up between the time it is put in storage and when it is sold in October. And it simply may not be possible to sell propane in advance. In that case, the retailer fills the storage throughout the summer, likely averages the cost of supply in all six tanks, and hopes conditions exist during the winter to make an acceptable margin on the storage position as the propane is delivered and sold.

Every retailer understands the scenario above in terms of supply cost and pricing. Perhaps the only thing not imaginable is the cost of building a tank farm of that size. Now we are going to show how using propane forwards functions in the same manner.

First, the process of physically buying propane is the same. The retailer buys from the same terminal and uses the same supplier and transportation company. None of this activity will take place in the summer; it will only take place in the winter when consumers are demanding propane. There is no reason for the retailer to add any storage cost.

At the same time the retailer would have been filling the storage tanks they will take propane forward positions for each month of winter. Forwards are month and volume specific. You can’t take one forward position to cover the winter. You cover the winter with six forwards, covering each month from October through March. There is a lot of flexibility in how to buy forwards. They can be bought for just about any volume and for up to three years out.

For example, in April, the retailer could take six forward positions for October through March for 30,000 gallons. That would be the equivalent of filling all six storage tanks in the same month. They could have the forwards priced for each month individually or get an average price over the six-month period. They could buy 10,000 gallons for each of the six winter months in April and repeat that again in May and June to price average. The examples could go on and on, but let’s say the retailer takes one futures position for October for 30,000 gallons. That is the equivalent of filling the October storage tank above in one day.

If a retailer filled his October storage tank on one day in April, he would be paying the wholesaler’s price, which would be based on the current or April propane values. Remember, the contract is Mont Belvieu’s day of lifting plus 10 cents. However, if the retailer took an October forward position on that same day, the price would be based on where October propane is trading at the time in Mont Belvieu. October propane is likely to be priced higher than April propane. The reason is that the market prices storage and time costs into the futures price.

But remember, the retailer should add storage cost to the propane bought in April, but will not deliver until October, to cover the investment in the storage and the time value of money, etc.

Since the forward is based on the value of propane at Mont Belvieu, Texas, the retailer will add the 15-cent difference between Mont Belvieu and the tank to establish supply cost in the tank. No need to add storage or time value of money costs. Both are built into the forward strike price already. Also, there is never an expectation you will take physical delivery of propane as part of the forward contract. They are written to show you buy at a certain price, called the strike price, and you will automatically close or sell it at the month average for the month in question.

Whether the retailer buys April propane at the pipeline and fills his storage and then adds the cost of storage to that price, or if he takes an October forwards position and adds the difference in the cost of propane between Mont Belvieu and his location, the cost of supply is likely to be very similar. Essentially, a retailer can use forwards to mimic supply costs as if he were buying spot propane and filling an unlimited tank farm.

With this example, we hope it is easy for the reader to see how the two, buy-and-store or take forward positions, would yield the same cost of supply. The retailer can use either to establish a fixed price offering to the customer as a hedge, or they cannot sell against the position and speculate.

Now for the difference that confuses many. When the retailer buys and stores propane, the cost is straightforward. There is no confusion. He gets invoiced by the supplier and the transportation company; he pays the bill, and costs are known immediately.

On the other hand, the forwards and physical activity of putting propane in the retailer’s tank are independent. Remember physically putting the propane in the retailer’s bulk tank will be the same as in the buy-and-store option. Same supplier, same transportation company, but it will take place in October. The cost of propane from the supplier will be based on the prices in October on the day of lifting. That will almost certainly be far different from the price used back in April when the forward was established and the fixed price was given to the customer. However, the forward position will offset whatever has happened with the price of propane during that time.

If the price of propane has gone up 10 cents between April and October, when wholesaler and transportation company invoices are paid, the retailer will show 10 cents less margin on the revenue received from the customer since his price was fixed. However, the strike price of the future will be 10 cents less than the monthly average, and it will pay the retailer the difference. That will offset the lower margin from the physical activity.

On the other hand, if propane prices were 10 cents lower, the retailer would make 10 cents more on the physical activity once invoices are paid and revenue is received from the customer. However, in this case, the retailer will have to use the 10 cents extra margin made on the physical activity to pay the loss on the forward. So, whether the retailer bought and stored or used forwards to build a fixed price for the customer, the margin will be the same.

Interestingly, it is at the point of writing the check in the last scenario when retailers seem to make a disconnect between using forwards and buying and storing or doing pre-buys. They seem to forget that when they buy-and-store or pre-buy and prices go down, it’s the same loss as the forward. In all three cases, the only way to avoid making less margin in a falling market is to have sold the propane position at the same time it was bought. In all three cases, if the sales were not made against the position, which means they were speculative, the loss is the same.

If a retailer can get past the check-writing part when prices fall, they can see a lot of advantages to using forwards. The positions can be opened and closed easily. Money does not exchange hands when they are established. It settles, and money exchanges hands at the end of the month that is covered. For example, an October forward settles after the market closes on the last day of October.

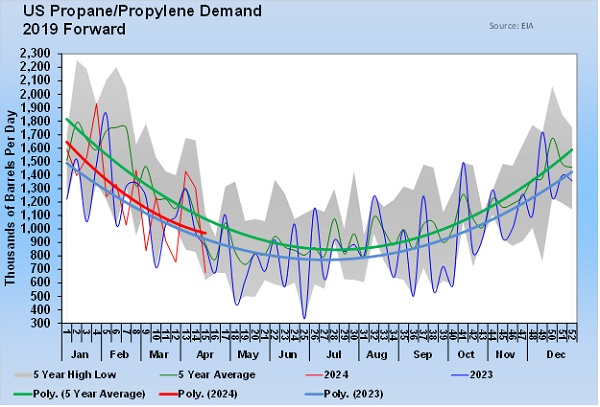

It is not always the case, but right now the forwards market is pricing where the storage and cost of money are minimal. For example, as we write, front November Mont Belieu propane is trading at 64.75 cents, and October 2024 propane is just 4 cents higher. Remember, there is no money upfront to establish the forward position. Also, storage is built into the price, which makes it cheap storage. Sometimes the spread will be much higher, so even though the price is higher for the future, it is still a good value when you consider the alternatives.

All charts courtesy of Cost Management Solutions.

Call Cost Management Solutions today for more information about how client services can enhance your business at 888-441-3338 or drop us an email at info@propanecost.com.